The next volume of the "Peoples and Cultures" series is devoted to the ethnography of the indigenous peoples of the North-East of Siberia: the Ainu, Aleuts, Itelmens, Kamchadals, Kereks, Koryaks, Nivkhs, Chuvans, Chukchi, Eskimos, Yukagirs. This is the first generalizing work, which presents a detailed description of the ethnic cultures of all Paleo-Asian peoples of the Far East. The book acquaints the reader with the results of the latest research in anthropology, archeology, ethnic history of these peoples, traditional economy, social organization, beliefs, customs and holidays, unique folk and professional art, folklore, social life. New materials from museums, state archives, and private collections are introduced into scientific circulation. Especially interesting are photographs of the Northern Expedition of the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of the Russian Academy of Sciences of the 1950s-2000s.

For ethnologists, historians and a wider range of readers.

The peoples of the North and the Far East are called small in number. This term includes not only the demography of the ethnos, but also its culture - traditions, customs, way of life, etc.

The legislation clarified the concept of smallness. These are peoples with a population of less than 50 thousand people. Such manipulation made it possible to "throw out" the Karelians, Komi, Yakuts from the list of northern peoples.

Who stayed

What are the small Russia known today? These are Yukaghirs, Enets, Tuvans-Tojins, Kereks, Orochi, Kets, Koryaks, Chukchi, Aleuts, Eskimos, Tubalars, Nenets, Teleuts, Mansi, Evens, Evens, Shors, Evenks, Nanai, Nganasans, Alyutors, Veps, Tazy , Chuvans, Soyts, Dolgans, Itelmens, Kamchadals, Tofalars, Umandians, Khanty, Chulkans, Negidal, Nivkhs, Ulta, Sami, Selkups, Telengits, Ulchi, Udege.

Indigenous peoples of the North and their language

They all belong to the following language groups:

- sami, Khanty and Mansi - to the Finno-Ugric;

- the Nenets, Selkups, Nganasans, Enets - to the Samoyed;

- dolgans - to the Turkic;

- evenks, Evens, Negidals, terms, Orochi, Nanai, Udege and Ulchi - to the Tungus-Manchu;

- chukchi, Koryak, Itelmen speak families;

- eskimos and Aleuts - Eskimo-Aleutian.

There are also isolated languages. They are not part of any group.

Many languages \u200b\u200bhave already been forgotten in colloquial speech and are used only in the everyday life of the old generation. Mostly they speak Russian.

Since the 90s, they have been trying to restore the lessons of their native language in schools. It is difficult to do this, since he is not well known to anyone, it is difficult to find teachers. When studying, children perceive their native language as a foreign language, since they rarely hear it.

Peoples of Russia: features of appearance

The appearance of the indigenous peoples of the North and the Far East is monolithic in contrast to their language. In terms of anthropological properties, most can be attributed to Small stature, dense build, light skin, black straight hair, dark eyes with a narrow cut, a small nose - these signs indicate this. An example is the Yakuts, the photos of which are given below.

With the development of the north of Siberia in the 20th century by the Russians, some peoples, as a result of mixed marriages, acquired a Caucasian outline of their faces. The eyes became lighter, their cut was wider, and brown hair began to appear more and more often. The traditional way of life is also acceptable for them. They belong to their native nation, but their names and surnames are Russian. The peoples of the North of Russia try to stick to their nation nominally for a number of reasons.

First, to preserve benefits that give the right to free fishing and hunting, as well as various subsidies and benefits from the state.

Secondly, to maintain numbers.

Religion

Previously, the indigenous peoples of the North were mainly followers of shamanism. Only at the beginning of the 19th century. they converted to Orthodoxy. During the Soviet Union, they had almost no churches and priests left. Only a small part of the people have kept icons and observe Christian rites. The majority adhere to traditional shamanism.

The life of the peoples of the North

The land of the North and the Far East is of little use for agriculture. The settlements are mainly located on the shores of bays, lakes and rivers, since only sea and river trade routes work for them. The time by which it is possible to deliver goods to villages across the rivers is very limited. Rivers are quickly freezing. Many become captives of nature for many months. It is also difficult for anyone from the mainland to get to their villages. At this time, you can get coal, gasoline, as well as the necessary goods only with the help of helicopters, but not everyone can afford it.

The peoples of the North of Russia observe and honor age-old traditions and customs. These are mainly hunters, fishermen, reindeer herders. Despite the fact that they live according to the examples and teachings of their ancestors, in their everyday life there are things from modern life. Radios, walkie-talkies, gasoline lamps, boat motors and much more.

Small peoples of the North of Russia are mainly engaged in reindeer husbandry. From this trade they get skins, milk, meat. They sell most of them, but there is enough for themselves. Deer are also used as transport. This is the only means of transportation between villages that are not separated by rivers.

Kitchen

Raw food diet prevails. Traditional dishes:

- Kanyga (half-digested contents of a deer's stomach).

- Deer antlers (growing horns).

- Kopalchen under pressure).

- Kiwiak (carcasses of birds decomposed by bacteria, which are stored in the skin of a seal for up to two years).

- Deer bone marrow, etc.

Work and trade

Some peoples of the North are developed, but only the Chukchi and Eskimos are engaged in it. Fur farms are a very popular type of income. Arctic foxes and minks are bred on them. Their products are used in sewing workshops. They are used to make both national and European clothes.

There are mechanics, salesmen, minders, nurses in the villages. But most of the reindeer herders, fishermen, hunters. Families who do this all year round live in the taiga, on the banks of rivers and lakes. They occasionally stop by the villages to buy various products, essential goods or send mail.

Hunting is a year-round trade. The peoples of the Russian Far North hunt on skis in winter. They take with them small sleds for equipment, mostly dogs carry them. More often they hunt alone, rarely in a company.

Housing of small peoples

These are mainly log houses. Nomads move with plagues. It looks like a tall, conical tent, the base of which is reinforced with multiple poles. Covered with chum deer skins sewn together. Such dwellings are transported on a sleigh with reindeer. Chum is usually placed by women. They have beds, bedding, chests. There is a stove in the center of the chum; some nomads have a bonfire, but this is rare. Some hunters and reindeer herders live in ravines. These are slatted houses, also covered with skins. They are similar in size to a construction trailer. Inside there is a table, bunk bed, oven. Such a house is transported on a sleigh.

Yaranga is a more complex wooden house. There are two rooms inside. The kitchen is not heated. But the bedroom is warm.

Only the indigenous peoples of the North still know how to build such dwellings. Modern youth are no longer trained in this kind of craft, as they mostly tend to leave for the cities. Few people remain to live according to the laws of their ancestors.

Why are the peoples of the North disappearing

Small nations are distinguished not only by their low numbers, but also by their way of life. The peoples of the European North of Russia retain their existence only in their villages. As soon as a person leaves and over time he moves to another culture. Few settlers come to the lands of the Northern peoples. And children, growing up, almost all leave.

The peoples of the North of Russia are mainly local (autochthonous) ethnic groups from the West (Karelians, Vepsians) to the Far East (Yakuts, Chukchi, Aleuts, etc.). Their population in their native places is not growing, despite the high birth rate. The reason is that almost all children grow up and leave the northern latitudes for the mainland.

In order for such peoples to survive, it is necessary to help their traditional economy. Reindeer pastures are rapidly disappearing due to the extraction of gas and oil. Farms are losing profitability. The reason is expensive food and the impossibility of grazing. Water pollution is affecting fisheries, which are becoming less active. Small peoples of the North of Russia are disappearing very rapidly, their total number is 0.1% of the country's population.

Face to face

You can't see the face.

Great things are seen at a distance.

Sergey Yesenin

We examined the reflection of the face of Europe's gene pool in three mirrors - the Y chromosome, mitochondrial DNA and the autosomal genome. However, even such a three-dimensional display will still be incomplete if we do not turn from Europe as a whole to the faces of individual peoples - to the genetic ties of this or that people of Europe with the rest of the European world. Such consideration allows not only to see the place of this or that ethnic gene pool among its close and distant neighbors. It gives more - to see exactly how the general picture of the European gene pool is formed from individual puzzles. Perhaps this will allow us to discern the paths of history in the addition of this general picture. For this purpose, the Y-chromosome mirror is most useful: its information content is comparable to that of genome-wide autosomal panels, and the palette of the studied populations is incomparably richer.

The genetic portrait of individual peoples against the background of the entire European gene pool is best outlined genetic distance maps... They show how the gene pool of a given nation fits into the general panorama of the peoples of Europe. Based on the entire set of haplogroups, maps of genetic distances show for a given people how peculiar it is, with whom it is similar, from whom it differs, how far its genetic ties with other peoples of Europe and nearby regions extend.

Genetic distance maps are created like this. First, a series of maps is built - each haplogroup has its own map. Each map is a numerical matrix - a very dense grid that evenly covers the entire mapped area. The frequency of a given haplogroup at a given geographical point is recorded in each of the many grid points (on the maps provided, almost 200 thousand grid points cover the mapped territory). Then the group of populations of interest to us is selected (it is called the reference) - say, Poles - from which genetic distances to each node of the grid (including the area of \u200b\u200bthe Poles themselves) will be calculated. The average frequencies of haplogroups from Poles are also taken - and for each point in Europe, the genetic distance from these frequencies in Poles to frequencies at a given point on the map is calculated. These data are enough to calculate the genetic distance from the frequencies of haplogroups in Poles to the frequencies of haplogroups in every point of Europe. These genetic distances are mapped. Then we take Serbs as a reference population, for example, and repeat all the same actions with the maps. And we get a map of the genetic landscape, showing the degree of similarity of the Y-chromosomal gene pool of Serbs with the Y-chromosomal gene pool of each population of Europe. And so for any selected population - ethnos or subethnos.

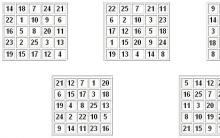

However, what to do with the fact that different populations have been studied for different sets of haplogroups? Of course, when constructing genogeographic maps, interpolated values \u200b\u200bare calculated for each point of the map, even if there are few control points (directly studied populations). But if we want to describe the gene pool of all populations in a single panel of haplogroups in the most accurate way when constructing maps of genetic distances, then the panel of haplogroups begins to shrink like shagreen skin. Our team uses an extensive panel of SNP markers (44 main and 32 additional haplogroups, as well as 32 more “newest” haplogroups, as described in Section 1.3), and we studied most of the populations of Eastern Europe using this broad panel. But in order to evenly represent all corners of Europe on the maps of genetic distances, at this stage of the study of the European gene pool, this panel, unfortunately, we had to reduce to eight main European haplogroups - E1b-M35, G-M201, I1-M253, I2a-P37, J-M304, N1c-M178, R1a-M198, R1b-M269.

Further research and mass screening of European populations for the sub-branches of these haplogroups, which are discovered due to the complete sequencing of the Y chromosome, will gradually refine these maps. When reading any map, one must remember that this model was created for the amount of information available on a given time slice: both the array of populations and the panel of haplogroups are limited. Therefore, it is important to pay attention not to the details of the relief, but to the most general and stable structures of the genetic landscape.

Genetic distance maps can be built for all peoples of Europe. In this monograph, we will not present everything, but many - 36 maps of genetic distances from 36 ethnic groups and sub-ethnic groups of Europe, the most important for the rest of the book chapters. These 36 genetic landscapes are grouped into six series:

Episode 1: the peoples of northeastern Europe(Karelians and Vepsians, Estonians, Izhorsk Komi, Priluzian Komi, Lithuanians, Latvians, northern Russians, Finns);

Episode 2: East and West Slavs(central and southern Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Polesie Belarusians, Poles, Kashubians, Slovaks, Czechs, Sorbs) ;

Episode 3: Non-Slavic Peoples of Eastern Europe(Bashkirs, Kazan Tatars, Mishars, Chuvashs, Moksha and Erzya);

Episode 4: in the north of the Balkans(Moldovans, Romanians, Gagauz, Hungarians, Slovenes);

Episode 5: South Slavs(Macedonians, Serbs, Croats, Bosnians, Herzegovina);

Episode 6: Framing Europe(Albanians, Swedes, Nogais).

5.1. PEOPLES OF NORTHEASTERN EUROPE (SERIESI)

This series includes eight maps of genetic distances - not only from the gene pools of ethnic groups (Karelians and Vepsians, Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, and Finns), but also from individual sub-ethnic groups (Komi Izhma, Komi Priluz, Russian North). Almost all of these maps are united not only by the geographic region, but also by the similarity of the genetic landscape. At the same time, the linguistic affiliation of these peoples is striking in its diversity. There are also Western Finno-speaking peoples (the Baltic-Finnish branch of the Finno-Ugric languages) - Karelians, Estonians, Finns; and the eastern Finnish-speaking Komi (the Permian branch of the Finno-Ugric languages); and the Slavs - the northern Russians; and the Balts are Latvians and Lithuanians. And, nevertheless, their gene pools are in many ways similar. To make sure of this, consider the entire series of maps - eight maps of genetic distances from each of the eight reference gene pools (Fig. 5.2-5.9). And in order to see the differences between each of the eight maps from the generalized genetic landscape of North-Eastern Europe, we present the average map of genetic distances (Fig. 5.1). Such a generalized landscape was obtained as a result of simple arithmetic operations with the matrices of maps: summing all eight maps (for each point of the map, the values \u200b\u200bof eight maps of haplogroups at this point were summed up) and dividing the resulting summary map by eight.

MAPPING THE SIMILARITY WITH THE KAREL AND WEPS GENE POOL (Fig.5.2)