The first tools for grinding grain into flour were a stone mortar and pestle. A certain step forward in comparison with them was the method of grinding grain instead of grinding. People very soon became convinced that grinding flour turns out much better. However, it was also extremely tedious work.

The big improvement was the move from forward and backward movement of the grater to rotation. The pestle was replaced by a flat stone that moved across a flat stone dish. From the stone that grinds the grain, it was already easy to move to the millstone, that is, to make one stone slide while rotating along the other. Grain was gradually poured into the hole in the middle of the upper stone of the millstone, fell into the space between the upper and lower stone and was ground into flour.

This hand mill was most widely used in Ancient Greece and Rome. Its construction is very simple. The base of the mill was a stone convex in the middle. An iron pin was located on its top.

The second, rotating stone had two bell-shaped depressions connected by a hole. Outwardly, it resembled an hourglass and was empty inside. This stone was planted on the base. A strip was inserted into the hole.

When the mill rotated, the grain, falling between the stones, was ground. The flour was collected at the base of the lower stone. These mills came in a variety of sizes, from small ones like modern coffee grinders to large ones that were driven by two slaves or a donkey. With the invention of the hand mill, the process of grinding grain was made easier, but it was still laborious and difficult. It is no coincidence that it was in the flour-milling business that the first

history is a machine that worked without the use of the muscular strength of a person or animal. This is a water mill. But first, the ancient masters had to invent the water engine.

The ancient water machines-engines evolved, apparently, from the irrigation machines of the chaduphons, with the help of which they raised water from the river to irrigate the banks. Chadouphon was a series of scoops that were mounted on the rim of a large wheel with a horizontal axis. When the wheel was turned, the lower buckets were immersed in the water of the river, then raised to the top point of the wheel and overturned into the chute.

At first, such wheels rotated by hand, but where there is little water, and it runs quickly along a steep channel, the wheel began to be supplied with special blades. Under the pressure of the current, the wheel rotated and itself scooped up water. The result is the simplest automatic pump that does not require the presence of a person for its work. The invention of the water wheel was of great importance to the history of technology. For the first time, a man got at his disposal a reliable, versatile and very easy to manufacture engine.

It soon became apparent that the motion created by the waterwheel could be used not only for pumping water, but also for other purposes, such as grinding grain. In flat areas, the speed of the river flow is small in order to rotate the wheel by the force of the jet impact. To create the necessary pressure, they began to dam the river, artificially raise the water level and direct the stream along the chute to the wheel blades.

However, the invention of the engine immediately gave rise to another task: how to transfer the movement from the water wheel to that device,

which should do work useful for a person? For these purposes, a special transmission mechanism was needed that could not only transmit, but also convert rotary motion. To solve this problem, the ancient mechanics again turned to the idea of \u200b\u200bthe wheel.

The simplest wheel drive works as follows. Imagine two wheels with parallel axes of rotation, which are in close contact with their rims. If now one of the wheels starts to rotate (it is called the leading one),

then due to the friction between the rims, the other (driven) will also begin to rotate. Moreover, the paths traversed by the points lying on their rims are equal. This is true for all wheel diameters.

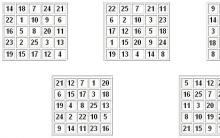

Consequently, a larger wheel will do, in comparison with a smaller one connected with it, as many times less revolutions as its diameter exceeds the diameter of the latter. If we divide the diameter of one wheel by the diameter of the other, we get a number that is called the gear ratio of a given wheel drive. Imagine a gear with two wheels in which the diameter of one wheel is twice the diameter of the other.

If a larger wheel is driven, we can use this transmission to double the speed of movement, but this will halve the torque. Such a combination of wheels will be convenient when it is important to get a higher speed at the exit than at the entrance. If, on the contrary, a smaller wheel is driven, we will lose speed at the output, but the torque of this transmission will double. This transmission is useful where you need to "increase the movement" (for example, when lifting heavy weights).

Thus, using a system of two wheels of different diameters, it is possible not only to transmit, but also to transform the movement. In actual practice, transmission wheels with a smooth rim are almost never used, since the clutches between them are not rigid enough, and the wheels slip. This disadvantage can be eliminated by using gear wheels instead of smooth wheels.

The first wheel gears appeared about two thousand years ago, but they became widespread much later. The point is that cutting teeth requires great precision. In order for the second wheel to rotate evenly, without jerking or stopping, with uniform rotation of one wheel, the teeth must be given a special outline, in which the mutual movement of the wheels would be performed as if they were moving over each other without sliding, then the teeth of one wheel would fall into hollows of the other.

If the gap between the teeth of the wheels is too great, they will hit each other and quickly break off. If the gap is too small, the teeth cut into each other and crumble. The calculation and manufacture of gears was a difficult task for ancient mechanics, but they already appreciated their convenience. After all, various combinations of gears, as well as their connection with some other gears, provided enormous opportunities for transforming motion.

For example, after connecting a gearwheel with a screw, a worm gear was obtained, transmitting rotation from one plane to another. Using bevel gears, you can transfer rotation at any angle to the plane of the drive wheel. By connecting the wheel with a toothed ruler, you can convert the rotary motion into translational, and vice versa, and by attaching a connecting rod to the wheel, a reciprocating motion is obtained. To calculate gears, the ratio of not the diameters of the wheels is usually taken, but the ratio of the number of teeth of the driving and driven wheels. Often multiple wheels are used in a transmission. In this case, the gear ratio of the entire transmission will be equal to the product of the gear ratios of the individual pairs.

When all the difficulties associated with obtaining and transforming motion were successfully overcome, a water mill appeared. For the first time its detailed structure was described by the ancient Roman mechanic and architect Vitruvius. The mill in ancient times had three main components, interconnected into a single device:

1) a motor mechanism in the form of a vertical wheel with blades rotated by water;

2) a transmission mechanism or transmission in the form of a second vertical gear wheel; the second gear wheel rotated the third horizontal gear wheel - gear;

3) an actuator in the form of millstones, upper and lower, and the upper millstone was mounted on the vertical gear shaft, with which it was set in motion. Grain was poured from a funnel-shaped bucket above the upper millstone.

The creation of the water mill is considered an important milestone in the history of technology. It became the first machine to be used in production, a kind of pinnacle that ancient mechanics reached, and the starting point for the technical quest for Renaissance mechanics. Her invention was the first timid step towards machine production.

There is little data on the early history of grinding (yes, there is such a story) in our area. Initially, here, as elsewhere in the world, they used a grain grater (where the grain was ground) and a grater (in fact, with which the grain was ground) to obtain flour. One fragment of a grain grater was found in our area during archaeological research of the Udmurt University. The labor of grinding grain with these devices was incredibly hard, had a low efficiency (you can rub it by hand with two stones) and was a specific female type of labor service. Until the mills appeared ...

And they appear in the Kama region (and therefore in our country), about a thousand years ago, in the 11th century. Scientists explain this change with an increase in the amount of grain obtained, which is associated with an improvement in agriculture and an increase in yields. In general, "life has become better, life has become more fun." The hand mill, in comparison with the grain grinder, heralded a technical revolution.

The principle of operation of a circular (according to the scientific rotational) mill is simple - a runner (upper millstone) carried out rotational movements along a bed - a motionless lower millstone, and grain was poured between the working surfaces of the millstones, which was ground into flour.

The revolutionary method at one time was successfully used in the Zyuzdinsky region until the middle of the XX century. Yes, not only was it used - in the territory of our region, a millstone was mined, which was traded outside the region. It is known that semi-finished products for mills were mined near the villages of Selukovy, Korablevy, Levinsky, repair near Gordino, as well as on Kuvakush. As for the volume of production, in the middle of the XIX century. up to 10,000 poods (160,000 kilograms !!!) were taken out of the millstone. They sold material for mills in neighboring volosts and in Glazov.

In addition to stone millstones, wooden mills have perked up in our area. Two circles were cut, iron plates with pointed edges were stuffed on their working sides, a handle was attached on top - the machine was ready.

But let's get back a little earlier. The millstones are millstones, and the equipment does not stand still - water mills appear, which further increase the speed and efficiency of grinding. However, a water mill is not an expensive pleasure; only wealthy peasants or the state could afford it. Part of the grain was given as payment for grinding. In the funds of our museum there is a milling ticket dated 1920, which gives the right to grind 3 poods of 20 pounds of grain (56 kg).

The practice of paying for grinding remained in the USSR, right up to wartime. Moreover, during the war years it was forbidden to grind grain in hand mills (obviously, this was caused by wartime conditions, the reluctance of the state to lose even a small percentage of grain receipts to state funds as a result of "unauthorized" grinding). Here is what one of the many Leningraders evacuated to our area during the war years recalled about it:

« In the summer we worked on the collective farm: we fed the sheaves to the horse-driven thresher, and in the evening and early in the morning we drove the horses to the pasture and back. We were then 11-12 years old ... we were counted workdays on the collective farm and paid for them with grain. Then my grandmother and I secretly ground this grain in the underground on a hand mill. Grinding was prohibited, so a homemade mill (two large round wooden blocks with steel teeth and a handle) was transported from house to house at night by dragging on a children's sled. From the rye flour obtained in this way, grandmother baked delicious pancakes with potatoes from her own gardenand".

After the war, the threshing fee was canceled and the use of hand mills was no longer prohibited. Back in the 1950s-1970s. they are used in private farmsteads for obtaining flour or cereals, but nothing lasts forever - it became easier to buy flour in a store than to grow grain and grind it by hand on millstones. There are still a lot of such wooden mechanisms in the old and abandoned houses of the Afanasyevsky district: when people moved, there was no need to take the mill with them, it is a pity to throw it away, so they still stand there ...

Literature:

- Belitser V.N. Among the Zyuzdian Komi-Perm // Brief communications of the Institute of Ethnography. M., 1952. Issue. 15.

- Bratchikov A. A few words about the natural resources of the Gordinsky volost and about the present state of agriculture in it. // VGV 1865, no. 45.

- Goldina R.D., Kananin V.A. Medieval monuments of the upper reaches of the Kama. Sverdlovsk, 1989.

- Kalitkin B. Severe times [Electronic resource]. Access mode: http://www.proza.ru/2011/02/07/171 (saved copy).

- Sarapulov A.N. Medieval implements for grain processing in the Perm Cis-Urals // Vestnik ChelGU. 2013, no. 18.

M. S. Dzhuraev

MILLING HISTORY: FROM SIMPLE GRAINS TO MILLS

Key words: history of flour milling, grain grinder, stone mortar, hand mill, millstones

In the course of a long history, mankind has developed a simple technology for the milling production of methods for producing flour from cereal grains using water mills. Already at an early stage of the primitive communal system, people used the grains themselves for food. It has been established that in the late Paleolithic era, people learned to grind grains, at first just with stones, and then specially adapted stone tools appeared - hand grain grinders. The manual grinding of wheat and other cereals was a laborious process, which was mainly occupied by women. The use of the power of water flow as a source of energy has become an important stage in human economic activity. The water mill was one of the first technical inventions in which the power of the flow of water replaced the muscle power.

Grain grater. The grain grater is one of the most ancient tools of human labor, which played a significant role in the development of production. Despite the antiquity of origin, the grain grater has not completely gone out of use. There are still mountain villages where these simple tools are used. This type of tool, made of solid stones of special rocks and in the shape of a simple saddle, is used for grinding flour. In the well-known ancient Greek epic of Homer, the grain grinder is casually mentioned, and also the method of using this tool is reported (18, 280).

In the archeology of Central Asia, grain grinders are very frequent finds during excavations of agricultural settlements. For example, at the famous site of the Eneolithic and Bronze Age - the settlement of Sarazm (IV-II millennium BC), graceful stone grains of various shapes, made from stones of different rocks, were discovered (19, 89).

Flat stones were used as raw materials for the manufacture of grain graters: oval-elongated, scaphoid, rectangular, amorphous. They varied in shape and weight. Grain grains found from the cultural layers of Sarazm were mainly of medium size and large: 60-70 cm long, 10-15 cm wide, and in shape

In the form of a saddle and a rook (17, 30).

In Khorezm, grain graters were found measuring 15-20 cm in length, 11-11.8 cm in width, made of stones of hard rocks. These grain graters are dated to the III-II millennium BC (14, 90). Scaphoid grain graters had a bend on the surface with the end raised up, they are well processed. In some cases, only the surface parts of the graters were processed. The upper edges of the grain grinder surface were processed by abrasive technique. The working part of the grain grinders was finished in a point - chased way. Many grain grinders had a very worn look. This indicates that they have been in long-term use, and in some granulators, as a result of prolonged use, tubules and cracks have formed. The rear part of the large grain grinders at the same time remained convex. An example of this is the grain grinders found in 6 living quarters of Sarazm. Some of Sarazm's grain grinders were used for secondary grinding of ocher. Some grain graters found in the settlements of Jaytun and Altyndepe (from 22 to 45 cm long and 35 cm wide) were used for secondary grinding of grain (17, 30-31). The grains of Sarazm are made exclusively of flat stone slabs, as well as cobblestones, granite. They had a deep-oblong, cupped shape (19, 89). The upper stones or chimes were of different sizes. They were made mainly of sandstone. They also had ellipsoidal, scaphoid and disc-shaped shapes. These graters have come down to our times only in the form of fragments. During the manufacture of these chimes, a special alignment technique was used

and cladding. One part of them had a flat or convex appearance. In almost all chimes, the border between the edges and the working surface was round. As a result of long-term use and heavy wear, they acquired a smooth and mirror-like surface. Grain grain sizes ranged from 15-26.5 cm in length, 9.4-12.4 cm in width and 12 cm in thickness (17.31). Grain in grain graters was ground with two stones: the lower stone was larger, and the middle was slightly flat and had a small depression. The upper stone, called a grater, had a slightly smaller size and was round in shape. The stones also varied in weight. With the help of these two stones, the grains were ground to obtain flour. With the help of these millstones, dried fruits, salt and much more were also ground. The conditions for grinding flour with grain graters were as follows: women holding the grain grater with both hands, sat down next to it and, leaning forward, pressed the grater, moved it back and forth, in this way crushing the grains. As a result of long-term use, stones were worn out and small particles of stone often fell into and mixed with flour (19, 569-570).

In 1954-1956 A.P. Okladnikov and B.A. Litvinsky was explored by more than 20 settlements of the Kairakkum culture of the Bronze Age. Archaeologists have found many tools, including grain grinders, stone pestles, etc. Studies have shown that these items were obtained mainly by gouging various forms of granite and porphyrite (7, 11-12). During the excavations in 16 rooms, many tools were also found.

In the cave site Obishir 1 and 5, located in the valley of the Sokh River, archaeologists found stone tools, among which there were also millstones (9, 15). Many grains were also discovered during the study of the monuments of ancient Ustrushana. They were made from hard rock sandstone (13, 188).

The grains of high-mountain settlements in the Sokha valley were called "dastos" (9, 60). In the mountainous Wakhan and Ishkashim they were used and called "dos-dos" (1.91).

The Scythian tribes of the Black Sea region used oval-shaped grain grinders. They were slightly curved and had depressions in the middle working part (4, 78).

Grains are also found in large quantities in many

monuments of the Early Bronze Age of Dagestan. They were usually made from rounded boulders of dense limestone as well as sandstone. Almost all of them were scaphoid. Such grain graters were used without the slightest change in shape until the early Middle Ages, i.e. until they were replaced by round millstones (5, 12).

For example, in the layers of Derbent of the Albanian time, a large number of grain graters were found, made of hard local stones of sandstone, shell rock and large river cobblestones. They were different in size: the smallest is 29 cm long, the largest is 52 cm, with a width of 10-25 cm and a thickness of 5-10 cm (6, 29).

The Tajiks in the mountain valleys of Afghan Badakhshan also milled flour with similar grain graters. This is due to the fact that less grain was grown in the highlands. The main food ration of this population was mulberry, which was ground on stone graters in a primitive way. To get mulberry flour, or rather powder. Most of the population of Kuhistan and Badakhshan was called by the Tajiks of neighboring villages as tutoids (3, 207).

Until recently, many cults and rituals of mountain Tajiks were associated with grain graters. These ceremonies symbolized the completion of a long cycle of growing cereals and receiving flour. A festive meal was prepared from the first flour. For example, the Khufs organized a feast called "almof" (1,153).

During archaeological excavations in the Kavat-Kalinsky oasis of Khorezm, a hearth was discovered and two pits with fragments of grain graters were discovered next to the hearth (14,154). The deliberate destruction of grain graters could be associated with the idea of \u200b\u200bcyclical renewal of nature. Also, some grain grinders served for two or three centuries. They were usually passed down from generation to generation.

Stone stupas - "uguri sangin". In the recent past, they met in cities and mountain villages of northern Tajikistan. According to U. Eshonkulov, in the Middle Ages and modern times, small metal and bronze mortars were used in some villages. But they were used mainly for grinding seeds, apricots, nuts, etc., mainly for

therapeutic purposes (19, 570).

More than three dozen stone mortars with pestles of cylindrical, cuboid, rectangular, bowl-shaped and oval shapes were found on the site of ancient Penjikent, dating from the 5th-8th centuries. They were made of hard stone, including marbled limestone, sandstone, diorite, and other rocks. The dimensions of the mortars found ranged from 12 to 26 cm in length, 10-19 cm in width, 6-13.5 cm in height, and 4-1.9 cm in wall thickness; the diameter of the recess is 28-13.5 cm, the depth of the container is 3.1-17.5 cm.

Together with mortars, pestles (40 pieces) of various shapes and colors were also found: cone-shaped, round, oval, cylindrical, wooden with one or two working ends. The raw materials for them were mainly hard sandstone, marble-like limestone, single green pebbles and dense hard shale. In order for the pestles to be of a certain shape, they were finished with an abrasive technique and a point-cut method. As a result of light blows in the mortar in its working places, the surfaces were ground, flat vertical facets of utilization. In many pestles, cracks were observed, wear as a result of prolonged use of which occurred during friction inside the mortar. The length of the pestles reached from 20 to 36 cm, the thickness - from 4.2 to 12.8 cm, the diameter of the spherical pestle reached from 5.5 to 11.4 cm (17, 32-33). In the village of Zebon, a pestle 40 cm long was found, made by the impact-point method. The tool has a thinned neck, highlighted by the head, the working part is ovoid, about 7-8 cm wide (19, 570). According to ethnographic materials, in the village of Khuf, fried and dried grains were also ground up in stone mortars (1, 239).

In the Middle Ages, small metal, bronze mortars were also used in the life of mountain Tajiks, but they have not survived to this day. After the incorporation of Central Asia into Russia, steel mortars with pestles appeared here, which are still used in the mills of the cities of Northern Tajikistan.

In addition to stone and metal mortars, there are also wooden mortars made of willow, walnut, mulberry, and other hard woods. However, they are short-lived and wear out quickly. They differ depending on the application.

for small and medium-sized - "khovancha". Their sizes range from 20 to 40 cm, with a diameter of up to 15-25 cm. Large mortars - “khovan” usually ranged in height from 60 to 120 cm, with a diameter of up to 50-80 cm.

Hardwood pestles were used to grind grain at home. They were thick and sturdy. In the middle of the pestles, oblong-shaped pestles were made to grip with both hands. Two people worked with heavier pestles, standing on both sides against each other and holding on to the pestle. In such wooden mortars, various grains were ground, including pure rice to the hull, and dried fruits, salt, grain and other cereals were often crushed with it.

Until recently, large wooden stupas were used in Khujand and its suburbs. In addition to cereals, dry bread, salt, dried fruits and other food products were ground in them. The method of making the stupa was very simple. A large diameter apricot, walnut, apple and other tree with a diameter of about 1.20 m was cut out. This trunk was installed in an upright position and a burning coal fire or a tandoor fire was placed on it in order to make a depression. Then hot oil was poured into this depression and kept for 24 hours. Further work was performed by master carpenters, who made an oval hole using a hammer and a cutting blade. Unfortunately, in our time this method of making pestles is lost (15).

The population of Central Asia had many methods of grinding grain. For example, the Turkmen used to grind grain crops with their hands in a mortar. In their language, this device was called "juices" (16, 78). The Kirghiz called it “soku” (2, 67).

Hand mill. The hand mill was one of the earliest man-made tools used to grind grain and make flour. According to a number of researchers, hand mills were first produced in Western Asia. Small fragments of stone millstones were found in the cultural layers of Sarazm of the 3rd-2nd millennium BC. The earliest hand mills were oval stones with a flat working surface and a through hole. They differ in shape and weight. As a rule, the millstones were made of hard rocks. Hand mills with a millstone diameter of 30-50 cm were typical for the entire Middle East (19, 91). For example, dia-

meters of millstones of hand mills in Khorezm (VII-VIII centuries) were from 32 to 48 cm, with a thickness of 4-6 cm (14, 96).

In the Middle Ages, hand mills were widespread throughout Central Asia. In remote mountain villages, hand mills have survived to this day. They are passed from generation to generation and are widely used in the household.

The way of using hand mills was well described by U. Eshonkulov: “both millstones had a rounded shape, the lower one with a depression in the middle (5-6 cm), the upper one had a through hole, the width of which exceeded the width of the lower depression by 23 cm; at the edge of the surface there was a 4-5 cm depression for the stick. Before grinding the grain, a tablecloth was first spread, on which the mill was installed. A short stick of hard wood - an axis - was fixed in the recess of the lower millstone, and the upper free one rotated around it. With the right hand, they rotated the handle of the upper millstone, with the left hand they poured grain into the hole. Often two people worked: one turned the millstones, the other poured grain. The resulting flour was sieved through a fine sieve and finely ground from coarse one was separated (19, 570).

The area where the millstones were mined and made was archaeologically recorded. In the area of \u200b\u200bthe suburb of Khurmi Penjikent, on the right bank of the Zerafshan River, there is a mountain sai called "Sangbur" ie quarry. Fragments of millstones from hand mills from the Sangbur area are found in many monuments of the Zerafshan valley, starting from the 3rd-5th centuries. From the 7th to the 20th centuries, the volume of extraction of millstones can be traced, as evidenced by their numerous fragments. According to the testimony of old residents of the Sangbur village, this quarry has functioned for more than 15 centuries. More than 20 fragments of hand millstones were found in Penjikent and its surrounding villages. In the southern part of the city, in the area of \u200b\u200bthe villages of Gurdara and Savr, several dozen more fragments of millstones were found. A series of hand millstones was made of hard rock stones brought by the mudflows of the Zeravshan River.

In the Middle Ages, in many villages of mountainous Sogd, the simplest way of processing grain functioned - a hand mill. The Sogdians called them "Khutana", that is. - self-driving. The term "hutana" is still used by the Yagnob in the meaning of "mill".

The famous ethnographer A.S. Davydov discovered two hand mills in the village of Sayyod, Shaartuz district. The indigenous population called them “dastos.” According to A.C. Davydov, grinding was an exclusively female business. Women brought their grain to the miller's house and ground it themselves at the owner's mill. In return, they gave him 1 bowl of flour.

In the Amu Darya oasis, wealthy families rarely worked on hand mills themselves, mostly hiring day laborers who were paid 2 to 7 pounds of grain a day.

According to U. Jakhonov, the Tajiks of the northern group of districts of Tajikistan called the hand mill “yarguchok” (9, 60-61). Ethnographer H.H. Ershov, who collected his field material in the Gissar valley, as well as in the city of Karatag, notes that “it is also worth mentioning the device of a hand-painted paint mill -“ yarguchok ”, on which dyes were ground and irrigated (10.88-89).

The Eastern Slavs called the hand mill differently: Russians and Belarusians - zhorny, zhoranki; northern Russians - kletets, ermak; Ukrainians - zhorna. The hand mill was used mainly for grinding salt and, very rarely, for making flour. Here, as in the Tajik village of Karatag, potters usually grind quartz sand and lead oxide in hand mills. In addition, in some regions of Ukraine there is still a custom of grinding grain into flour in a hand mill, from which the bridesmaids bake a wedding loaf (11, 118-119). In this regard, it should be especially noted that in the villages of Northern Tajikistan, special wedding bread is still baked at the weddings of the bridesmaids and put on a festive tablecloth (15).

In the XVII-XX centuries. in many cities and villages, mills stood on large irrigation canals. And in some even steam rooms, which ground up to 1.5 tons of wheat. In remote mountain villages, where they had no idea of \u200b\u200ba water mill at all, hand mills remained the main method of producing flour in the 50s-60s. XX century

Until the mid-50s of the XX century. water and hand mills were a means of providing the population of Northern Tajikistan and its mountain villages with food flour.

LITERATURE:

1.Andreev M.S. Tajiks of the Khuf valley (Upper Amu Darya). -Stalinabad, 1956, - \u200b\u200bIssue. II.

2. Bezhakovich A.C. Historical and ethnographic features of Kyrgyz agriculture. Essays on the history of the economy of the peoples of Central Asia and Kazakhstan. // Proceedings of In.etn. them. H.H. Miklouho-Maclay. New series, vol. XCVIII. - L., 1973.

3.Vavilov N.I., Bukinich D.D., Agricultural Afghanistan. - L., 1929.

4.Gavrilyuk H.A. Home production and everyday life of the steppe Scythians. -Kiev, 1989.

5.Gadzhiev M.G. Stone processing in Dagestan in the early Bronze Age // Crafts and crafts of ancient and medieval Dagestan. Digest of articles. - Makhachkala, 1988.

6.Gadzhiev M.S. Crafts and crafts of Derbent of the Albanian time // Crafts and crafts of ancient and medieval Dagestan. Digest of articles. - Makhachkala, 1988.

7. Gulyamova E. Archaeological and numismatic collections of the Institute of History, Archeology and Ethnography of the Academy of Sciences Taj. SSR. (Short review). - Stalinabad, 1989.

8. Davydov A.C. Diaries. Hissar ethnographic expedition of 1974 // Archives of the Institute of History, Archeology and Ethnography named after V.I. A. Donisha. Folder number 2, inventory number 19. - Dushanbe, 1974.

9. Jakhonov U. Agriculture of the Tajiks of the Sokh Valley in the late 19th - early 20th centuries. - Dushanbe, 1989.

Y. Ershov H.H. Karatag and its crafts. - Dushanbe, 1984. P. Zelenin D.K. East Slavic ethnography. - M „1991.

12.Ilyina V.M. Materials on the survey of nomadic and sedentary indigenous economy and land use in the Amu-Darya region. - Issue. I. - Tashkent, 1915.

13.Negmatov N.N., Khmelintsky S.E. Medieval Shahristan. (material culture of Ustrushana). - Issue. 1. - Dushanbe, 1966.

14. Nerazik E.E. Rural settlements of Afrigtskiy Khorezm. - M „1966.

15. Pirkuliyeva A. Domestic crafts and crafts of the Turkmen of the Middle Amu-Darya valley in the second half of the 19th-20th centuries. -Ashgabat, 1973.

17.Razzakov A. Sarazm (Tools of labor and economy according to experimental and traceological data). - Dushanbe, 2008.

18. Semyonov S.A. The origin of agriculture. - L., 1974. 19. Eshonkulov U. History of the agricultural culture of mountainous Sogd (from ancient times to the beginning of the 20th century). - Dushanbe, 2007.

The history of the mill industry, from simple grain grinders to millstones

M. S. Juraye

Key words: grain grinder, stone mortar, hand mill, millstones, tools, flour

In the article, the author, on the basis of field material, presents the history of the evolution of water and hand mills of a group of cities and mountain villages in Northern Tajikistan. The author emphasizes that in the past, due to the lack of centralized delivery to the southern regions of Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan, water and hand mills were the only source of providing the population with bread products.

The History of Milling from Simple Grain Graters up to a Millstone

Key words: grain grater, stone mortar, millstones, tools of labor, flour

Proceeding from the collected field material the author expounds the history of the evolution concerned with water and manual mills of the group of towns and mountains villages of Northern Tajikistan. The author lays an emphasis upon the fact that in the past because of non-availability of a central delivery into southern areas of Russia, the Ukraine and Kazakhstan manual mills served as the only source of providing population with bread products.

Millstones are one of the most ancient inventions of mankind. It is quite possible that it appeared even earlier than the wheel. What do millstones look like? What functions do they perform? And what is the principle of this ancient movement? Let's figure it out!

Millstones - what is it?

According to scientists, our ancestors began to use this simple device in the Stone Age (10-3 millennium BC). What are the millstones? It is a primitive mechanical device consisting of two rounded blocks. Its main function is to grind grain and other plant products.

The word comes from the Old Slavonic "zhrnve". This can be translated as "heavy". The unit really could have a fairly solid weight. Millstones are mentioned in the Tale of Bygone Years. In particular, the following phrase can be found in the annals:

"Groats rye and izmul with his own hands."

The word is often used in a figurative sense. Suffice it to recall such phrases as "millstones of war" or "millstones of history." In this context, these are cruel and fatal events in which a person or a whole nation may find themselves.

The image of millstones can be found in heraldry. For example, on the coat of arms of the small town of Höör, in the south of Sweden.

A bit of history

In ancient times, people grinded grains, nuts, shoots, rhizomes in millstones, and also ground iron and dyes. Once they could be seen in almost every rural house. Over time, flour-grinding technologies improved, water mills appeared, and even later - windmills. The difficult and exhausting work was shifted onto the shoulders of the forces of nature - wind and water. Although at the heart of the work of any mill remained the same millstone principle.

Earlier in the villages there was a special caste of artisans who were engaged in the manufacture of millstones, as well as the repair of individual parts. During constant work, the millstones were erased, their surfaces became smooth and ineffective. Therefore, it was necessary to sharpen them periodically.

Today millstones are history. Of course, few people today use these bulky units in everyday life. Therefore, they gather dust in museums and at various exhibitions, where curious tourists and lovers of antiquity can gaze at them.

The design and principle of operation of the millstones

The design of this mechanism is extremely simple. It consists of two round blocks of the same size stacked on top of each other. In this case, the lower circle is immobilized, and the upper one rotates. The surfaces of both blocks are covered with a relief pattern, due to which the grain grinding process is carried out.

The stone millstones are set in motion by means of a special cross-shaped pin mounted on a vertical wooden rod. It is very important that both units are correctly aligned and adjusted. Poorly balanced millstones will result in poor grind quality.

Most often, the millstones were made of limestone or fine-grained sandstone (or from what was at hand). The main thing is that the material is sufficiently hard and durable.

Municipal budgetary educational institution Mukshinskaya secondary comprehensive school School NPK "Step into the future" Research work About mills in the past we will put in a word Author: Vakhrushev Zakhar Sergeevich 4th grade student of MBOU Mukshinskaya secondary school Leader: Abrosimova Valentina Viktorovna, primary school teacher MBOU Mukshinskaya secondary school Content Introduction …………………………………………………………………. 2 Chapter 1 1.1. Mill - what is it? ............................................. .............................. 4

1.2. Water mill ……………………………………………… .. 4 1.3. Windmill ……………………………………………… 5 1.4. When did the mills appear? ............................................. .......... 5 Chapter 2 2.1. Mills of our region …………………………………………… .. 7 2.2. The device of the hand mill …………………………………… .. 8 2.3. From the history of one mill ………………………………………… 9 Conclusion …………………………………………………………… .12 Sources of information …… ………………………………………………… 13 Appendices ……………………………………………………………… 15 Introduction The tree has roots, people have a past. Cut off the roots - the tree will dry out. The same happens to people if they do not want to know the life of their fathers and grandfathers. A person comes and goes to earth, but his work - evil or good - remains, and from what work is left, living joy or burden and sorrow. In order not to increase hardships and not to multiply grief, the living must know where what comes from. Isai Kalashnikov's wonderful words can serve as a motto for every person who is interested in the history of their ancestors, the way of life, and the way of life of their distant ancestors. Many household items are gradually leaving our everyday life. Today, not only city children, but also 1

many villagers no longer see in action such objects as a rocker, a grapple, a poker, a cast iron, and even spinning wheels, on which "three girls were spinning under the window late in the evening." And the tub, in which Moidodyr offered to splash? It is good that many schools have museum rooms or museums. Unique objects, documents collected over a long period of time by children and teachers throughout the village, as well as in nearby villages, found their corner in these ancient repositories. When you visit a museum, you involuntarily ask yourself questions. Who did they belong to? What is the history of these things? And what were they for? How few people are left today who have seen these objects in action with their own eyes. How difficult it is today to find out who they belonged to and who made them. In the museum of our school there is a unique thing that, as my grandmother told me, belonged to our family, or rather to my great-grandmother on my father's line, Lyubov Alekseevna Serebryannikova. (Appendix 1). This is a hand mill. Looking at this exhibit, I could not understand how you can grind flour or get cereals with the help of two tulles? I wanted to study the history of this object, its structure, who used it, and how the mill ended up in our museum, i.e. study the biography of this exhibit; also learn about other types of mills. (Appendix 2) So, the object of research is various types of mills. The subject of research is a hand mill - a croupier. Purpose: to study the local history material associated with the history of various types of mills used in the territory of our region, including the hand mill - kruporushki. Objectives: to study the local history literature on the history of the origin of mills; to collect information about hand mills, crumbling, operating in private farms of peasants; 2

meet people who can talk about the subjects being researched. Based on the foregoing, we put forward a hypothesis: when meeting with people of the older generation, working with scientific local history literature, you can establish the history of the emergence of things and describe them. In the work, materials of the MBOU Mukshinskaya museum were used, materials published in the supplement of the regional newspaper "Oshmes" Yakshur of the Bodinsky district, also used reference and local history literature, Internet resources. Practical value: my work can be used in local history lessons, class hours, and during excursions. Chapter 1.1. What is a mill? We understand perfectly well that the time of mills is long gone. This ancient symbol, which contains the elements of water, wind and air, and also personifies the harvesting and fertility, still keeps all its secrets and mysteries, and does not cease to fascinate the hearts and souls of the older generation, and we, the younger generation, perceive a mill as a fabulous item. For example, from the fairy tale "Puss in Boots" by Charles Perrault. A mill is a mechanism designed to grind various materials. Mills differ from crushers in finer grinding of the material. The mill can be water, wind and manual. Why were the mills created? The mills generated the energy needed to pump water, make paper, grind grain, cut timber, and 3

many other industrial tasks, but still the main job of the water wheel was the grinding of grain. What kind of mills are there? 1.2. Water Mill The construction of a water mill was based on the same standard design, the principle of which is very similar to that of a windmill, only the wheel is driven by water. Previously, there was rarely a mill on any river. In the countryside, she was something special. The following types of work were carried out here: grinding grain into flour and groats, crushing oatmeal, obtaining flaxseed oil. A quick-witted miller could arrange in a mill barn both sifting flour and a felting-bar. From the nearest neighborhood, carts with grain stretched to the mill, and back the same carts with fresh flour - the drivers and horses were a little white with flour dust. The road often went through a mill dam. From the pool under the dam it was always possible to catch fish, ducks and geese swam in the pond, and the grass was richly green in the floodplain meadows. The pond and dam brought the rural landscape to life. (Appendix 3) Most of the people used a water mill, but in those places where their installation was not possible, windmills already appeared. 1.3. Windmill. Russian carpenters have created many different and ingenious versions of windmills. Already in our time, more than twenty varieties of their design solutions have been recorded. Of these, two principal types of mills can be distinguished: "post-mill" and "smock". The first were common in the North, the second - in the middle zone and the Volga region. Both names also reflect the principle of their structure. Windmills were built on the territory of Udmurtia. 4

At the pillar mills, the mill barn revolved on a pillar dug into the ground. Either additional pillars or a pyramidal log frame served as a support. The principle of shatter mills was another lower part of them was stationary, and the smaller upper part rotated under the wind. And this type in different areas had many options. (Appendix 4) 1.4. When did the mills appear? Water Mill. In a poem dated 98 - 90. BC, Antipart welcomes the appearance of the first mills: “Give rest to your hands, about working women, and sleep peacefully! In vain will the rooster announce to you the coming of the morning! Dao entrusted the work of the girls to the nymphs, and now they easily jump on the wheels, so that the shaken axles rotate with their spokes and make the heavy millstone rotate. " In the era of Charlemagne, in 340, as a borrowing from Rome, a water mill appeared in Germany, on the Moselle River. At the same time, the first water mills appeared in Galia (France). In Russia, water mills appeared no later than the 12th century. On flat rivers, the water pressure necessary for the operation of the mill was provided by dams. The blades of the water wheel are lowered into the water and set in motion by the flow of the river. The water mill was used not only for grinding grain into flour, but in the production of paper for grinding raw materials, in the production of gunpowder. So in the middle of the 16th century, paper mills worked on the rivers, a blacksmith's hammer was adapted to a water wheel - it turned out "samokov". In 1655, two powder mills were built on the Yauza River by decree of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich. The creation of a water mill is considered an important step in the history of technology. This was the first step towards machine production. Windmills appeared at the end of the X beginning of the XI century. in France and England, and then in Holland. Now the landscape of this country is impossible 5

imagine without wind turbines. Many improvements to windmills were made in Holland. So, here a kind of braking devices appear, with the help of which it was possible to very quickly stop the rotating millstones. In Russia mills appeared at the end of the 15th to the middle of the 17th century. Due to the invasion of the Tatar-Mongols in Russia, the development of the country and the beginning of the technical revolution were delayed in comparison with Western countries. Chapter 2. 2.1. Mills of our region Today, models of mills, more often windmills, can be seen when decorating gardens, parks and even in the Izhevsk Zoo. (Appendix 5) But there is a unique object for our republic - a water mill, which is located in the Uvinsky district, in the village of Turyngurt. Even in Russia, few such historical monuments have survived. As usual, there is a picturesque large building on the edge of the village by the pond. High log walls, a couple of small windows and a dam. And all this against the backdrop of an overgrown pond. It looks impressive and even fabulous. The mill is almost 100 years old, but it can still work. You can grind flour or connect to drying or sorting units. If you connect it to a generator, then the water mill will provide electricity. (Appendix 6) In addition, more recently, you could see it in action. Unfortunately, in 2013 the last miller, Boris Obukhov, passed away. 6

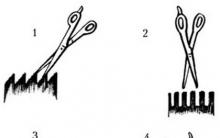

The operating windmill can be seen in Ludorvae - an open-air museum. The mill was built back in 1912, but it got to the territory of the museum only in 1994, where it was transported from the village of ChemoshurKuyuk, Alnash district. The mill is 12 meters high and has 3 floors. The tent type of mills, to which this exposition belongs, was widespread in the territory of southern Udmurtia. The mill was closed for a long time, but since 2009, visitors have been allowed here. This mill is the only surviving windmill in the territory of Udmurtia. (Appendix 7) According to local residents, there were 4 water mills on the territory of the Mukshinskoye municipal district in the middle of the 20th century. In the village of Kykva, on a pond near the farm, on the Pukhovka pond between the villages of Mukshi and Dmitrievka, in the village of Kutonshur, in the village of Mukshi on the upper pond. In addition to water mills, there was a windmill in the village of Druzhny, because the village was far from the river. In addition to wind and watermills, handmills were often used in villages, especially if the settlement was located at a distance from the mills. In the next paragraph, we will consider how a hand mill works. 2.2. The device of the hand mill The hand mill is made of a solid log, consists of two separate parts. About 2 thousand small cast iron plates are driven into the inner sides of the upper and lower parts of the mill, thanks to which the grain was crushed and turned into flour when the upper part of the mill rotated. A tray is attached to the side at the bottom of the mill, along which the ground grain was slowly poured into the prepared container. In the upper part there are three holes: one was used for filling the grain, the other for the handle with which the mill rotated. The handles were inserted differently, depending on the amount of grain and the number of people working. If one person worked, then the handle was inserted short, if several, then long. For 7

strength and greater pressure, a rail was inserted into the third hole and attached to the ceiling. In order for the flour to flow in the right direction, the edges of the lower part of the mill were often covered with iron in a circle. The height of the mill was made different, it depended on the master or the customer, and the dimensions reached 1 meter in height and half a meter in width. (Appendix 8) But how did the grain turn into flour on this unit? Grain, through the hole in the upper part, fell on the contacting surfaces of the logs, broke, entered the box along the slotted grooves, then swept away into the bag through the holes. After the first passage of the grains, they turn into cereals, with repeated grinding it was possible to get flour. Subsequently, there was sifting through a sieve. This product was used to make cereals and stews. The resulting crushed grain often contained sawdust from wooden millstones. Considering that such units were used in difficult lean years, it is quite reasonable that sawdust remained in the product as a filler, to which nettle and quinoa were also added. In the postwar years, peasants used a slightly improved model of a hand mill in their farms. On the contacting surfaces of the millstones radially, from the center to the periphery, "cast iron" fragments from cracked cast irons and pots were hammered, polished flush with each other. The rye grain was crushed twice and then sieved through a sieve and sieve. From one bucket of grain, up to ¾ of a bucket of "coarse" flour was obtained. Wooden millstones were installed so that there was a certain gap. In this variant, sawdust from the tree did not get into the crushed product. Similar grain crushers were used in favorable times to prepare sprinkles for pets. The peasants received grain for workdays for work on the collective farm. 8

Such a mill was not in every peasant household, only wealthy peasants, for whom it was made by craftsmen. Making a grinder mill required certain skills and time. 2.3. From the history of one mill The hand mill-corpusher has recently appeared in the museum of our school and has taken an honorable place here. The mill was handed over to the museum by a resident of the village of Mukshi Vakhrusheva Lia Borisovna, my grandmother, a native of the Debessky district of the UR. (Appendix 10) The history of the appearance of this exhibit in our museum is interesting because it came to us not from our neighboring villages, but from the Debesky region. The hand mill was brought by the mother of Leah Borisovna Serebrennikova Lyubov Alekseevna, when she moved to her daughter's place of residence. She was born in 1936 in the village of Starye Siri of the Kez district of the UR. Lyubov Alekseevna very early became an orphan and together with her brother went to the villages, helped people with the housework, thereby earning a living. At the age of 18, she married Boris Timofeevich Serebrennikov in the village of Berezovka, Debessky district. The family lived in prosperity, and there for the first time she saw this hand mill, at which she later had to work herself. The water mill was far away and it was inconvenient to drive every time. Then the grocer came to the rescue. Most often it was used to grind animal flour and prepare cereals. Rye, barley, wheat, peas were ground. Although this work was not easy, the children were often forced to grind, the children took turns spinning the mill. As mentioned above, such mills were not in every family, so the mill was often asked for use 9

fellow villagers. And father-in-law Timofey Stepanovich and mother-in-law Matryona Vasilievna were kind people, ready to help their fellow villagers, and always shared their property, which is why they enjoyed great respect in the village. But at the same time, they treated her with care. According to their stories, this mill was made for the family of Timofey Stepanovich's parents at the end of the 19th century by a wandering craftsman (unfortunately, no one knows the name of the master). This craftsman walked around the villages and, at the request of the residents, made the corrugators, while working he lived in the family, became a member of it. Lyubov Alekseevna, the thing was dear, she inherited it from her husband's parents, so when moving to her daughter, she decided to take the mill with her in order to convey the living memory of her ancestors to her grandchildren and great-grandchildren through the memory of things. This is the legend of this exhibit, and after the death of her mother, Liya Borisovna decided to transfer the mill-grinder to the school museum, because in private households, except for family members, no one sees it and loses its value, and in the museum it again acquires this value. The museum receives a unique item that will give the opportunity to tell children about life, the way of life of our ancestors of the past centuries, to plunge into the world of our ancestors. (Appendix 9) 10

Conclusion From childhood to the end of our lives, everything that surrounds us on our earth is dear and dear to us. The names of lakes and ponds, rivers and streams, villages and villages, alleys and outskirts caress our ears and senses. These historical information, legends, and were telling about the life of our ancestors, are unique monuments of our antiquity, cultural centers of past eras, partly embodied in such a concept as a mill. But the mills themselves have always acted as such cultural centers for all people, at any time and in any country where peasants from different villages met in anticipation of grinding and there was an exchange of news, and economic discussions flared up. An unusual household item for a modern person, which belonged to my ancestors, gave impetus to the search for new knowledge. As a result of the search work, I confirmed the hypothesis that meetings with people of the older generation, work with scientific local history literature, allow us to establish the history of the emergence of things and describe them. Today the museum has about 300 exhibits, many of them do not have a history of the legend of their appearance in the museum and it is hardly possible to restore the belonging of some things. But all the same, there is an opportunity to establish where and how these or those antiquities were used, for example, how much an exhibit called "flail" can tell us, with the help of which the peasants knocked out the grains from the spikelets. Our goal, while there is an opportunity, it is necessary to fix everything, leave it for future generations. Mills have always been surrounded by mystery, covered with poetic legends, tales and superstitions. For example, "There are devils in every pool" and the water one, as it should be in fairy tales, also lives in the pool. Sources of information 11

1. Kalashnikov I. Cruel century. Publisher: EksmoPress, 1998 2. Shlyakhtina L.M "Fundamentals of Museum Business". Publisher: Vysshaya Shkola, 2009 3. "Oshmes" supplement of the regional newspaper "Rassvet" Yakshur-Bodyinsky District, No. 10, 2012 4. Image of a sieve. [Electronic publication] // Based on materials from the site ru.yandex.net/i? https: // im0tub id \u003d & n \u003d 13, 5. Image of a hand mill. [Electronic publication] // Based on materials from the site https://im0tubru.yandex.net/i? id \u003d & n \u003d 13 12

6. Ludorvai - an open-air museum. [Electronic publication] // According to http://liveudm.ru/ludorvaymuzeypodotkryityim materials of the site nebom / 13

7. Turyngurt is an old water mill. [Electronic publication] // Based on materials from the site http://loveudm.ru/turyingurtstarinnayavodyanaya melnitsa / 8. Interesting facts about mills. [Electronic publication] // Based on materials from the site http://vaddoronin.narod.ru/WindMill_WindMill.html 22.03.2018 9. Sazonov D.A. Mill and corrugated business [Electronic publication] // Based on materials from the site http://davaiknam.ru/text/konkurs issledovateleskihk10. Model of a windmill [Electronic publication] // Based on materials from the site http://www.domechti.ru/wpcontent / uploads / 2013/05 / dekorativnaya melnicadlyasada08.jpg 11. Model of a windmill. [Electronic publication] // Based on materials from the site http://mobilizacia.kiev.ua/uploads/posts 12. Model of a water mill. [Electronic publication] // Based on materials from the site https://www.kursdela.biz/upload/medialibrary/0b5/0b5af287fedc15ac1bcec0 ded2f04351.jpg 13. A model of a water mill. [Electronic publication] // Based on materials from the site https://i.artfile.me/wallpaper/09102014/2048x1366/raznoemelnicy lesrekamelnicavodyanay874265.jpg Informants: 14.Abrosimova Valentina Viktorovna, b. 1955 15.Vakhrusheva Lia Borisovna, born in 1966 16. Serebrennikova Lyubov Alekseevna, 1932 14

Appendices 1 Alekseevna born in 1932, a resident of the village of Turnes, Debessky Serebrennikova Lyubov district Appendix 2 15

Hand mill. Exhibit of the local history museum MBOU Mukshinskaya secondary school Appendix 3 16

Water mills Appendix 4 17

Windmill 18

Appendix 5 Models of windmills for decorating garden plots Appendix 6 Water mill, Turyngurt, Uvinsky district, Udmurtia Appendix 7 19

Windmill Ludorvay - Open Air Museum Udmurtia Appendix 8 Device of a hand mill Appendix 9 20

Transfer of living memory of ancestors to grandchildren and great-grandchildren through the memory of things. Appendix 10 Vakhrusheva Liya Borisovna, a resident of the village of Mukshi 21

What to give a vegetarian for his birthday

Face cream at home - preparation rules

An ancient recipe for youth from Tibetan monks

How to drink clay to cleanse the body

Download maps slavic oracle