Lesson Objectives.

Educational: to form an idea of the main features and problems of demographic, social and economic development of the Russian Empire at the turn of the 18th-19th centuries; continue working on concepts, developing the ability to highlight the main idea, establish cause-and-effect relationships, compare, draw conclusions, work with supporting notes, condensed information

Download:

Preview:

Lesson topic: “The Russian Empire at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries”

History of Russia 8th grade.

Lesson objectives.

Educational: to form an idea of the main features and problems of demographic, social and economic development of the Russian Empire at the turn of the 18th-19th centuries; continue working on concepts, developing the ability to highlight the main idea, establish cause-and-effect relationships, compare, draw conclusions, work with supporting notes, condensed information.

Developmental: promote the development of students’ analytical skills, the ability to work with text information, and develop oral and written communication skills.

Educational: continue to develop teamwork skills, a sense of patriotism and pride in one’s country

Educational equipment: historical documents, textbook, handouts, presentation “Russia at the beginning of the 19th century”, interactive board, computer, map “Russian Empire at the beginning of the 20th century”.

During the classes:

Stage 1. Two students form a pair, two pairs form a group. Each of them has its own text and textbook paragraph:

1) the territory of Russia at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries. Population.

2) class system.

3) economic system.

4) political system.

For 10 minutes, everyone works with their text and begins filling out the table in their notebook from their column, entering the keywords:

Russian Empire at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century.

Stage 2. By agreement, one of the students tells his text. Another listens, asks clarifying questions, writes down key words, and then tells his friend his topic, now the first listener asks questions.

Stage 3. Change of pair. The first options in the group are swapped. Work continues in rotating pairs until each student has completed the entire table in their notebook. 5 min. working time for presenting the material and recording in the table. Total total time for work is 30 minutes.

Stage 4. Consolidation of knowledge.

Frontal work. Board test:

1. By the beginning of the 19th century, the population of Russia was

A) 46 million

B) 24 million

B) 128 million

D) 44 million

2. By the beginning of the 19th century, the largest class in Russia

A) merchants

B) landowners

B) peasants

D) clergy

3. The political system of Russia at the beginning of the 19th century is

A) Parliamentary republic

B) Autocratic monarchy

B) Theocratic state

D) Limited monarchy

4. The Russian Empire was:

A) Multinational state

B) Mono-ethnic state

Stage 5. Reflection.

Give your description of the country by writing opposite the letter the adjective that suits you:

R -

Homework: pp. 5-7.

Application:

Text No. 1.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Russian Empire was a huge continental country. It occupied a sixth of the land and stretched from the Baltic Sea to Alaska in North America. By the middle of the 19th century, the area of Russia reached 18 million sq. km. The country was divided into 69 provinces and regions, which in turn were divided into counties (in Belarus and Ukraine - into povets). On average, there were 10-12 districts per province. Groups of provinces in some cases were united into general governorships and governorships. Thus, three Lithuanian-Belarusian provinces (Vilna, Kovensk and Grodno, with the center in Vilna) and three Right Bank Ukrainian provinces (Kiev, Podolsk and Volyn, with the center in Kyiv) were united. The Caucasian governorship included the Transcaucasian provinces with its center in Tiflis.

Text No. 2.

in the 17th-18th centuries, the Cossacks were used by the state to guard external borders; in the 17th-18th centuries, the Cossacks, mainly the poorest part of them, formed the backbone of the rebels during the peasant wars, but at the turn of the 18th-19th centuries. the government established control over the Cossack regions, and in the 19th century. began to create new Cossack troops to guard the borders, for example Siberian and Transbaikal. The Cossacks were mainly state peasants. By the middle of the 19th century. in Russia there were 9 Cossack troops: Don, Black Sea (Kuban), Terek, Astrakhan, Orenburg, Ural, Siberian and Ussuri troops; The heir to the throne was considered the ataman of all Cossack troops. At the head of each army was a designated (appointed) ataman. The village atamans were elected by the Cossacks themselves.

Text No. 3.

The main forms of feudal exploitation are corvee and quitrent.

The spread of the corvée form of exploitation applies primarily to the black earth provinces. In the central industrial provinces, where soil fertility was low, the quitrent form prevailed.

Landowners sought to increase the production of bread for sale. To do this, they reduced peasant plots and increased sown areas. The number of corvee days is increasing, and in some cases a month is being introduced.

month - a type of corvee. The landowner took away their plots from the peasants, forcing them to work only on his land. For this, he gave them a monthly allowance of food and clothing.

The increase in gross grain production occurred precisely because of the expansion of sown areas, while the corvee system could not be profitable and was in crisis. The productivity of forced labor was constantly falling, which is explained by the disinterest of peasants in the results of their labor.

The size of the quitrent for the first half of the 19th century. increased by 2.5-3.5 times. Since agriculture did not provide enough money for quitrent, peasants began to engage in non-agricultural activities, such as crafts. In winter, the carriage trade (transportation of goods on one's own sleigh) spreads. With the development of industry, the number of peasant otkhodniks increased, who went to work in factories, earning money there for quitrent (waste trade).

Contradictions also arose in the quitrent system. Thus, competition between peasant artisans is intensifying. On the other hand, the developing factory industry provided serious competition to peasant crafts. As a result, the earnings of quitrent peasants fell, their solvency decreased, and therefore the profitability of landowners' estates.

Text No. 4.

According to its political structure, Russia was an autocratic monarchy. The head of the state was the emperor (in common parlance he was traditionally called the king). The highest legislative and administrative power was concentrated in his hands.

The emperor ruled the country with the help of officials. According to the law, they were executors of the king's will. But in reality, the bureaucracy played a more significant role. The development of laws was in his hands, and it was he who put them into practice. The bureaucracy was the sovereign master in the central government bodies and in local ones (provincial and district). The political system of Russia was autocratic-bureaucratic in form. The word “bureaucracy” is translated as: the power of offices. All segments of the population suffered from the arbitrariness of the bureaucracy and its bribery.

The highest bureaucracy consisted primarily of noble landowners. The officer corps was made up of them. Surrounded on all sides by nobles, the tsar was imbued with their interests and defended them as his own.

True, sometimes contradictions and conflicts arose between the tsar and individual groups of the nobility. Sometimes they reached very acute forms. But these conflicts never captured the entire nobility.

The Russian Empire entered the new, 19th century as a powerful power. The capitalist structure strengthened in the Russian economy, but noble land ownership, which was consolidated during the reign of Catherine II, remained the determining factor in the economic life of the country. The nobility expanded its privileges, only this “noble” class owned all the land, and a significant part of the peasants who fell into serfdom were subordinated to it under humiliating conditions. The nobles received a corporate organization under the Charter of 1785, which had a great influence on the local administrative apparatus. The authorities kept a watchful eye on public thought. They brought to trial the freethinker A.N. Radishchev, the author of “Journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow,” and then they imprisoned him in distant Yakutsk.

Successes in foreign policy gave a peculiar shine to the Russian autocracy. During the course of almost continuous military campaigns, the borders of the empire were expanded: in the west, it included Belarus, Right Bank Ukraine, Lithuania, the southern part of the Eastern Baltic in the west, and in the south - after two Russian-Turkish wars - Crimea and almost the entire North Caucasus. Meanwhile, the internal situation of the country was fragile. Finance was threatened by constant inflation. The issue of banknotes (since 1769) covered the reserves of silver and copper coins accumulated in credit institutions. The budget, although it was reduced without a deficit, was supported only by internal and external loans. One of the reasons for the financial difficulties was not so much the constant costs and maintenance of the expanded administrative apparatus, but rather the growing arrears of peasant taxes. Crop failure and famine recurred in individual provinces every 3-4 years, and throughout the country every 5-6 years. Attempts by the government and individual nobles to increase the marketability of agricultural production through better agricultural technology, which was the concern of the Free Economic Union created in 1765, often only increased the corvee oppression of the peasants, to which they responded with unrest and uprisings.

The class system that had previously existed in Russia gradually became obsolete, especially in the cities. The merchants no longer controlled all trade. Among the urban population, it was increasingly possible to distinguish classes characteristic of a capitalist society - the bourgeoisie and workers. They were formed not on a legal, but on a purely economic basis, which is typical for a capitalist society. Many nobles, merchants, wealthy townspeople and peasants found themselves in the ranks of entrepreneurs. Peasants and burghers predominated among the workers. In 1825 there were 415 cities and towns in Russia. Many small towns had an agricultural character. In Central Russian cities, gardening was developed, and wooden buildings predominated. Due to frequent fires, entire cities were devastated.

The mining and metallurgical industries were located mainly in the Urals, Altai and Transbaikalia. The main centers of metalworking and textile industry were St. Petersburg, Moscow and Vladimir provinces, and Tula. By the end of the 20s of the 19th century, Russia imported coal, steel, chemical products, and linen fabrics.

Some factories began using steam engines. In 1815, the first domestic motor ship “Elizabeth” was built in St. Petersburg at the Berda machine-building plant. Since the middle of the 19th century, the industrial revolution began in Russia.

The system of serfdom, taken to the limit of non-economic exploitation, turned into a real “powder keg” under the building of a powerful empire.

The beginning of the reign of Alexander I. The very beginning of the 19th century was marked by a sudden change of persons on the Russian throne. Emperor Paul I, a tyrant, despot and neurasthenic, was strangled by conspirators from the highest nobility on the night of March 11-12, 1801. The murder of Paul was carried out with the knowledge of his 23-year-old son Alexander, who ascended the throne on March 12, stepping over his father’s corpse.

The event of March 11, 1801 was the last palace coup in Russia. It completed the history of Russian statehood in the 18th centuries.

Everyone pinned their hopes on the name of the new tsar, not the best: the “lower classes” for a weakening of landlord oppression, the “tops” for even greater attention to their interests.

The noble nobility, who placed Alexander I on the throne, pursued the old goals: to preserve and strengthen the autocratic serf system in Russia. The social nature of the autocracy as a dictatorship of the nobility also remained unchanged. However, a number of threatening factors that had developed by that time forced the Alexander government to look for new methods to solve old problems.

Most of all, the nobles were worried about the growing discontent of the “lower classes.” By the beginning of the 19th century, Russia was a power vastly spread over 17 million square meters. km from the Baltic to the Okhotsk and from the White to the Black Sea.

About 40 million people lived in this space. Of these, Siberia accounted for 3.1 million people, the North Caucasus - about 1 million people.

The central provinces were most densely populated. In 1800, the population density here was about 8 people per 1 sq. mile. To the south, north and east of the center, population density has decreased sharply. In the Samara Trans-Volga region, the lower reaches of the Volga and on the Don, it was no more than 1 person per 1 sq. mile. The population density was even lower in Siberia. Of the entire population of Russia, there were 225 thousand nobles, 215 thousand clergy, 119 thousand merchants, 15 thousand generals and officers, and the same number of government officials. In the interests of these approximately 590 thousand people, the king ruled his empire.

The vast majority of the other 98.5% were disenfranchised serfs. Alexander I understood that although the slaves of his slaves would endure a lot, even their patience had a limit. Meanwhile, oppression and abuse were limitless at that time.

Suffice it to say that corvee labor in areas of intensive agriculture was 5-6, and sometimes even 7 days a week. The landowners ignored the decree of Paul I on the 3-day corvee and did not comply with it until the abolition of serfdom. At that time, serfs in Russia were not considered people; they were forced to work like draft animals, bought and sold, exchanged for dogs, lost at cards, and put on chains. This could not be tolerated. By 1801, 32 of the 42 provinces of the empire were engulfed in peasant unrest, the number of which exceeded 270.

Another factor influencing the new government was pressure from noble circles demanding that they return the privileges granted by Catherine II. The government was forced to take into account the spread of liberal European trends among the noble intelligentsia. The needs of economic development forced the government of Alexander I to reform. The dominance of serfdom, under which the manual labor of millions of peasants was free, hindered technical progress.

The industrial revolution - the transition from manual production to machine production, which began in England in the 60s, and in France in the 80s of the 18th century - in Russia became possible only in the 30s of the next century. Market links between different regions of the country were sluggish. More than 100 thousand villages and villages and 630 cities scattered across Russia had little idea of how and how the country lived, and the government did not want to know about their needs. Russian lines of communication were the longest and least comfortable in the world. Until 1837, Russia did not have railways. The first steamship appeared on the Neva in 1815, and the first steam locomotive only in 1834. The narrowness of the domestic market hampered the growth of foreign trade. Russia's share in world trade turnover was only 3.7% by 1801. All this determined the nature, content and methods of the internal policy of tsarism under Alexander I.

Domestic policy.

As a result of a palace coup on March 12, 1801, the eldest son of Paul I, Alexander I, ascended the Russian throne. Internally, Alexander I was no less a despot than Paul, but he was adorned with external polish and courtesy. The young king, unlike his parent, was distinguished by his beautiful appearance: tall, slender, with a charming smile on his angel-like face. In a manifesto published on the same day, he announced his commitment to the political course of Catherine II. He began by restoring the Charters of 1785 to the nobility and cities, abolished by Paul, and freed the nobility and clergy from corporal punishment. Alexander I was faced with the task of improving the state system of Russia in a new historical situation. To conduct this course, Alexander I brought close to himself the friends of his youth - European educated representatives of the younger generation of noble nobility. Together they formed a circle, which they called the “Unspoken Committee”. In 1803, a decree on “free cultivators” was adopted. According to which the landowner, if he wished, could free his peasants by allocating them with land and receiving a ransom from them. But the landowners were in no hurry to free their serfs. For the first time in the history of autocracy, Alexander discussed in the Secret Committee the question of the possibilities of abolishing serfdom, but recognized it as not yet ripe for a final decision. Reforms in the field of education were bolder than on the peasant issue. By the beginning of the 19th century, the administrative system of the state was in decline. Alexander hoped to restore order and strengthen the state by introducing a ministerial system of central government based on the principle of unity of command. Triple need forced tsarism to reform this area: it required trained officials for the updated state apparatus, as well as qualified specialists for industry and trade. Also, in order to spread liberal ideas throughout Russia, it was necessary to streamline public education. As a result, for 1802-1804. The government of Alexander I rebuilt the entire system of educational institutions, dividing them into four rows (from bottom to top: parish, district and provincial schools, universities), and opened four new universities at once: in Dorpat, Vilna, Kharkov and Kazan.

In 1802, instead of the previous 12 boards, 8 ministries were created: military, maritime, foreign affairs, internal affairs, commerce, finance, public education and justice. But the old vices also settled in the new ministries. Alexander knew of senators who took bribes. He struggled to expose them with fear of damaging the prestige of the Governing Senate.

A fundamentally new approach to solving the problem was needed. In 1804, a new censorship charter was adopted. He said that censorship serves “not to restrict the freedom to think and write, but solely to take decent measures against its abuse.” The Pavlovsk ban on the import of literature from abroad was lifted, and for the first time in Russia, the publication of the works of F. Voltaire, J.J., translated into Russian, began. Rousseau, D. Diderot, C. Montesquieu, G. Raynal, who were read by the future Decembrists. This ended the first series of reforms of Alexander I, praised by Pushkin as “the wonderful beginning of Alexander’s days.”

Alexander I managed to find a person who could rightfully lay claim to the role of a reformer. Mikhail Mikhailovich Speransky came from the family of a rural priest. In 1807, Alexander I brought it closer to himself. Speransky was distinguished by the breadth of his horizons and strict systematic thinking. He did not tolerate chaos and confusion. In 1809, following the teachings of Alexander, he drew up a project for radical state reforms. Speransky based the government system on the principle of separation of powers - legislative, executive and judicial. Each of them, starting from the lower levels, had to act within the strictly defined framework of the law.

Representative assemblies of several levels were created, headed by the State Duma - an all-Russian representative body. The Duma was supposed to give opinions on bills submitted to its consideration and hear reports from ministers.

All powers - legislative, executive and judicial - were united in the State Council, whose members were appointed by the tsar. The opinion of the State Council, approved by the tsar, became law. Not a single law could come into effect without discussion in the State Duma and the State Council.

The real legislative power, according to Speransky's project, remained in the hands of the tsar and the highest bureaucracy. He wanted to bring the actions of the authorities, in the center and locally, under the control of public opinion. For the voicelessness of the people opens the way to the irresponsibility of the authorities.

According to Speransky’s project, all Russian citizens who owned land or capital enjoyed voting rights. Craftsmen, domestic servants and serfs did not participate in the elections. But they enjoyed the most important state rights. The main one was: “No one can be punished without a judicial verdict.”

The project began in 1810, when the State Council was created. But then things stopped: Alexander became increasingly comfortable with autocratic rule. The higher nobility, having heard about Speransky's plans to give civil rights to serfs, openly expressed dissatisfaction. All conservatives, starting with N.M., united against the reformer. Karamzin and ending with A.A. Arakcheev, falling into favor with the new emperor. In March 1812, Speransky was arrested and exiled to Nizhny Novgorod.

Foreign policy.

By the beginning of the 19th century, two main directions in Russian foreign policy had been determined: the Middle East - the desire to strengthen its positions in the Transcaucasus, the Black Sea and the Balkans, and the European - participation in the coalition wars of 1805-1807. against Napoleonic France.

Having become emperor, Alexander I restored relations with England. He canceled Paul I's preparations for war with England and returned him from the campaign to India. The normalization of relations with England and France allowed Russia to intensify its policy in the Caucasus and Transcaucasia. The situation here worsened in the 90s, when Iran began active expansion into Georgia.

The Georgian king repeatedly turned to Russia with a request for protection. On September 12, 1801, a manifesto was adopted on the annexation of Eastern Georgia to Russia. The reigning Georgian dynasty lost its throne, and control passed to the viceroy of the Russian Tsar. For Russia, the annexation of Georgia meant the acquisition of strategically important territory to strengthen its positions in the Caucasus and Transcaucasia.

Alexander came to power in an extremely difficult and tense situation for Russia. Napoleonic France sought dominance in Europe and potentially threatened Russia. Meanwhile, Russia was conducting friendly negotiations with France and was at war with England, France's main enemy. This position, which Alexander inherited from Paul, did not suit the Russian nobles at all.

Firstly, Russia maintained long-standing and mutually beneficial economic ties with England. By 1801, England absorbed 37% of all Russian exports. France, incomparably less rich than England, never brought such benefits to Russia. Secondly, England was a respectable, legitimate monarchy, while France was a rebel country, thoroughly imbued with a revolutionary spirit, a country headed by an upstart, a rootless warrior. Thirdly, England was on good terms with other feudal monarchies in Europe: Austria, Prussia, Sweden, Spain. France, precisely as a rebel country, opposed the united front of all other powers.

Thus, the priority foreign policy task of the government of Alexander I was to restore friendship with England. But tsarism did not intend to fight with France either - the new government needed time to organize urgent internal affairs.

The coalition wars of 1805-1807 were fought over territorial claims and mainly over dominance in Europe, which was claimed by each of the five great powers: France, England, Russia, Austria, Prussia. In addition, the coalitionists aimed to restore in Europe, right up to France itself, the feudal regimes overthrown by the French Revolution and Napoleon. The coalitionists did not skimp on phrases about their intentions to free France “from the chains” of Napoleon.

Revolutionaries - Decembrists.

The war sharply accelerated the growth of the political consciousness of the noble intelligentsia. The main source of the revolutionary ideology of the Decembrists were the contradictions in Russian reality, that is, between the needs of national development and the feudal-serf system that hampered national progress. The most intolerant thing for advanced Russian people was serfdom. It personified all the evils of feudalism - the despotism and tyranny that reigned everywhere, the civil lawlessness of most of the people, the economic backwardness of the country. From life itself, the future Decembrists drew impressions that pushed them to the conclusion: it was necessary to abolish serfdom, transform Russia from an autocratic state into a constitutional state. They began to think about this even before the War of 1812. Leading nobles, including officers, even some generals and high-ranking officials, expected that Alexander, having defeated Napoleon, would give freedom to the peasants of Russia and a constitution to the country. As it became clear that the tsar would not cede either one or the other to the country, they became more and more disappointed in him: the halo of a reformer faded in their eyes, revealing his true face as a serf-owner and autocrat.

Since 1814, the Decembrist movement has taken its first steps. One after another, four associations took shape, which went down in history as pre-Decembrist ones. They had neither a charter, nor a program, nor a clear organization, nor even a specific composition, but were busy with political discussions about how to change the “evil of the existing order of things.” They included very different people, who for the most part later became outstanding Decembrists.

The “Order of Russian Knights” was headed by two scions of the highest nobility - Count M.A. Dmitriev - Mamonov and Guards General M.F. Orlov. The “Order” plotted to establish a constitutional monarchy in Russia, but did not have a coordinated plan of action, since there was no unanimity among the members of the “Order”.

The “sacred artel” of General Staff officers also had two leaders. They were the Muravyov brothers: Nikolai Nikolaevich and Alexander Nikolaevich - later the founder of the Union of Salvation. The “Sacred Artel” organized its life in a republican way: one of the premises of the officers’ barracks, where the members of the “artel” lived, was decorated with a “veche bell”, upon the ringing of which all the “artel members” gathered for conversations. They not only condemned serfdom, but also dreamed of a republic.

The Semenovskaya artel was the largest of the pre-Decembrist organizations. It consisted of 15-20 people, among whom stood out such leaders of mature Decembrism as S.B. Trubetskoy, S.I. Muravyov, I.D. Yakushkin. The artel lasted only a few months. In 1815, Alexander I learned about it and ordered “to stop gatherings of officers.”

Historians consider the circle of the first Decembrist V.F. to be the fourth before the Decembrist organization. Raevsky in Ukraine. It arose around 1816 in the city of Kamenetsk-Podolsk.

All pre-Decembrist associations existed legally or semi-legally, and on February 9, 1816, a group of members of the “Sacred” and Semenovskaya artel, led by A.N. Muravyov founded the secret, first Decembrist organization - the Union of Salvation. Each of the society members had military campaigns of 1813-1814, dozens of battles, orders, medals, ranks, and their average age was 21 years.

The Union of Salvation adopted a charter, the main author of which was Pestel. The goals of the charter were as follows: to destroy serfdom and replace autocracy with a constitutional monarchy. The question was: how to achieve this? The majority of the Union proposed to prepare such public opinion in the country that, over time, would force the tsar to promulgate the constitution. A minority sought more radical measures. Lunin proposed his plan for the regicide; it consisted in having a detachment of brave men in masks meet the king’s carriage and finish him off with blows of daggers. Disagreements within salvation intensified.

In September 1817, while the guards were escorting the royal family to Moscow, members of the Union held a meeting known as the Moscow Conspiracy. Here I offered myself as the king of the murderer I.D. Yakushkin. But only a few supported Yakushkin’s idea; almost everyone was “terrified to even talk about it.” As a result, the Union banned the assassination attempt on the Tsar “due to the scarcity of means to achieve the goal.”

Disagreements led the Salvation Union to a dead end. Active members of the Union decided to liquidate their organization and create a new, more united, broader and more effective one. So in October 1817, the “Military Society” was created in Moscow - the second secret society of the Decembrists.

“Military Society” played the role of a kind of control filter. The main cadres of the Salvation Union and the main cadres and new people who should have been tested were passed through it. In January 1818, the Military Society was dissolved and the Union of Welfare, the third secret society of the Decembrists, began to operate in its place. This union had more than 200 members. According to the charter, the Welfare Union was divided into councils. The main one was the Root Council in St. Petersburg. Business and side councils in the capital and locally - in Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod, Poltava, Chisinau - were subordinate to her. The year 15.1820 can be considered a turning point in the development of Decembrism. Until this year, the Decembrists, although they approved of the results of the French Revolution of the 18th century, considered its main means - the uprising of the people - unacceptable. That's why they doubted whether to accept the revolution in principle. Only the discovery of the tactics of military revolution finally made them revolutionaries.

The years 1824-1825 were marked by the intensification of the activities of Decembrist societies. The task of preparing a military uprising was immediately set.

It was supposed to start it in the capital - St. Petersburg, “as the center of all authorities and boards.” On the periphery, members of Southern society must provide military support for the uprising in the capital. In the spring of 1824, as a result of negotiations between Pestel and the leaders of the Northern Society, an agreement was reached on unification and a joint performance, which was scheduled for the summer of 1826.

During the summer camp training of 1825, M.P. Bestuzhev-Ryumin and S.I. Muravyov-Apostol learned about the existence of the Society of United Slavs. At the same time, his unification with the Southern Society took place.

The death of Emperor Alexander I in Taganrog on November 19, 1825 and the interregnum that arose created a situation that the Decembrists decided to take advantage of for an immediate attack. Members of the Northern Society decided to start an uprising on December 14, 1825, the day on which the oath to Emperor Nicholas I was scheduled. The Decembrists were able to bring up to 3 thousand soldiers and sailors to Senate Square. The rebels were waiting for their leader, but S.P. Trubetskoy, who had been elected the day before as “dictator” of the uprising, refused to come to the square. Nicholas I gathered against them about 12 thousand troops loyal to him with artillery. With the onset of dusk, several volleys of grapeshot dispersed the rebel formation. On the night of December 15, arrests of the Decembrists began. On December 29, 1825, in Ukraine, in the area of the White Church, the uprising of the Chernigov regiment began. It was headed by S.I. Muravyov-Apostol. With 970 soldiers of this regiment, he carried out a raid for 6 days in the hope of joining other military units in which members of the secret society served. However, the military authorities blocked the area of the uprising with reliable units. On January 3, 1826, the rebel regiment was met by a detachment of hussars with artillery and dispersed by grapeshot. Wounded in the head S.I. Muravyov-Apostol was captured and sent to St. Petersburg. Until mid-April 1826, arrests of Decembrists continued. 316 people were arrested. In total, over 500 people were involved in the Decembrist case. 121 people were brought before the Supreme Criminal Court, in addition, trials were held of 40 members of secret societies in Mogilev, Bialystok and Warsaw. Placed “outside the ranks” P.I. Pestel, K.F. Ryleev, S.I. Muravyov-Apostol and P.G. Kakhovsky were prepared for the “death penalty by quartering”, replaced by hanging. The rest are distributed into 11 categories; 31 people of the 1st category were sentenced to “death by beheading”, the rest to various terms of hard labor. More than 120 Decembrists suffered various punishments without trial: some were imprisoned in the fortress, others were placed under police supervision. In the early morning of July 13, 1826, the execution of the Decembrists sentenced to hanging took place, then their bodies were secretly buried.

Socio-political thought in the 20-50s of the 19th century.

Ideological life in Russia in the second quarter of the 19th century took place in a difficult political situation for progressive people, intensifying reaction after the suppression of the Decembrist uprising.

The defeat of the Decembrists gave rise to pessimism and despair among some part of society. A noticeable revival of the ideological life of Russian society occurred at the turn of the 30s and 40s of the 19th century. By this time, the currents of socio-political thought had already clearly emerged as protective-conservative, liberal-oppositional, and the beginning had been made of revolutionary-democratic.

The ideological expression of the protective-conservative trend was the theory of “official nationality.” Its principles were formulated in 1832 by S.S. Uvarov as “Orthodoxy, autocracy, nationality.” The conservative-protective direction in the context of the awakening of the national self-awareness of the Russian people also appeals to “nationality”. But he interpreted “nationality” as the adherence of the masses to “original Russian principles” - autocracy and Orthodoxy. The social task of the “official nationality” was to prove the originality and legality of the autocratic-serf system in Russia. The main inspirer and conductor of the theory of “official nationality” was Nicholas I, and the Minister of Public Education, conservative professors and journalists acted as its zealous promoters. The theorists of the “official nationality” argued that the best order of things prevails in Russia, consistent with the requirements of the Orthodox religion and “political wisdom.” alexander industrial empire political

“Official nationality” as an officially recognized ideology was supported by the entire power of the government, preached through the church, royal manifestos, the official press, and the system of public education. However, despite this, enormous mental work was going on, new ideas were born, united by the rejection of the Nikolaev political system. Among them, Slavophiles and Westerners occupied a significant place in the 30-40s.

Slavophiles are representatives of the liberal-minded noble intelligentsia. The doctrine of the identity and national exclusivity of the Russian people, their rejection of the Western European path of development, even the opposition of Russia to the West, the defense of autocracy and Orthodoxy.

Slavophilism is an oppositional movement in Russian social thought; it had many points of contact with the Westernism that opposed it, rather than with the theorists of the “official nationality”. The initial date for the formation of Slavophilism should be considered 1839. The founders of this movement were Alexey Khomyakov and Ivan Kireevsky. The main thesis of the Slavophiles is proof of the original path of development of Russia. They put forward the thesis: “The power of power is for the king, the power of opinion is for the people.” This meant that the Russian people should not interfere in politics, giving the monarch full power. The Slavophiles viewed the Nicholas political system with its German “bureaucracy” as a logical consequence of the negative aspects of Peter’s reforms.

Westernism arose at the turn of the 30s and 40s of the 19th century. The Westerners included writers and publicists - P.V. Annenkov, V.P. Botkin, V.G. Belinsky and others. They argued for the common historical development of the West and Russia, argued that Russia, although late, was following the same path as other countries, and advocated Europeanization. Westerners advocated a constitutional-monarchical form of government on the Western European model. In contrast to the Slavophiles, the Westerners were rationalists, and they attached decisive importance to reason, and not to the primacy of faith. They affirmed the very value of human life as a bearer of reason. Westerners used university departments and Moscow literary salons to promote their views.

In the late 40s - early 50s of the 19th century, the democratic direction of Russian social thought was taking shape; representatives of this circle were: A.I. Herzen, V.G. Belinsky. This trend was based on social thought and philosophical and political teachings that spread in Western Europe at the beginning of the 19th century.

In the 40s of the 19th century, various socialist theories began to spread in Russia, mainly by C. Fourier, A. Saint-Simon and R. Owen. The Petrashevites were active propagandists of these ideas. A young official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, gifted and sociable, M.V. Butashevich-Petrashevsky, starting in the winter of 1845, began to gather young people interested in literary, philosophical and political novelties on Fridays at his St. Petersburg apartment. These were senior students, teachers, minor officials and aspiring writers. In March - April 1849, the most radical part of the circle began to form a secret political organization. Several revolutionary proclamations were written, and a printing press was purchased to reproduce them.

But at this point the activity of the circle was interrupted by the police, who had been monitoring the Petrashevites for about a year through an agent sent to them. On the night of April 23, 1849, 34 Petrashevites were arrested and sent to the Peter and Paul Fortress.

At the turn of the 40-50s of the 19th century, the theory of “Russian socialism” took shape. Its founder was A.I. Herzen. The defeat of the revolutions of 1848-1849 in Western European countries made a deep impression on him and gave rise to disbelief in European socialism. Herzen proceeded from the idea of an “original” path of development for Russia, which, bypassing capitalism, would come to socialism through the peasant community.

Conclusion

For Russia, the beginning of the 19th century is the greatest turning point. The traces of this era are enormous in the fate of the Russian Empire. On the one hand, this is a lifelong prison for the majority of its citizens, where the people were in poverty, and 80% of the population remained illiterate.

If you look from the other side, Russia at this time is the birthplace of a great, contradictory, liberation movement from the Decembrists to the Social Democrats, which twice brought the country close to a democratic revolution. At the beginning of the 19th century, Russia saved Europe from the destructive wars of Napoleon and saved the Balkan peoples from the Turkish yoke.

It was at this time that brilliant spiritual values began to be created, which to this day remain unsurpassed (the works of A.S. Pushkin and L.N. Tolstoy, A.I. Herzen, N.G. Chernyshevsky, F.I. Chaliapin).

In a word, Russia looked extremely diverse in the 19th century; it experienced both triumphs and humiliations. One of the Russian poets N.A. Nekrasov said prophetic words about her that are still true today:

You're miserable too

You and abundant

You are mighty

You are also powerless

If in the primary period of its development (XVI-XVII centuries) the political elite of the Russian state demonstrated an almost ideal foreign policy course, and in the 18th century made only one serious mistake in Poland (the fruits of which we are reaping today, by the way), then in the 19th century the Russian Empire, Although he continues to basically adhere to the paradigm of justice in his relationships with the outside world, he still commits three completely unjustified actions. These mistakes, unfortunately, still come back to haunt Russians - we can observe them in interethnic conflicts and a high level of distrust of Russia on the part of neighboring peoples “offended” by us.

Russian army crossing the Danube at Zimnitsa

Nikolay Dmitriev-Orenburgsky

The 19th century begins with the Russian sovereign taking upon himself the responsibility to protect the Georgian people from complete extermination: on December 22, 1800, Paul I, fulfilling the request of the Georgian king George XII, signed the Manifesto on the annexation of Georgia (Kartli-Kakheti) to Russia. Further, in the hope of protection, Cuba, Dagestan and other small kingdoms beyond the southern borders of the country voluntarily joined Russia. In 1803, Mingrelia and the Imeretian kingdom joined, and in 1806, the Baku Khanate. In Russia itself, the working methods of British diplomacy were tested with might and main. On March 12, 1801, Emperor Paul was killed as a result of an aristocratic conspiracy. The conspirators associated with the English mission in St. Petersburg were unhappy with Paul's rapprochement with France, which threatened the interests of England. Therefore, the British “ordered” the Russian emperor. And they didn’t deceive - after the murder was completed, they in good faith paid the perpetrators an amount in foreign currency equivalent to 2 million rubles.

1806-1812: third Russian-Turkish war

Russian troops entered the Danube principalities in order to induce Turkey to stop the atrocities of Turkish troops in Serbia. The war was also fought in the Caucasus, where the attack of Turkish troops on long-suffering Georgia was repelled. In 1811, Kutuzov forced the army of Vizier Akhmetbey to retreat. According to the peace concluded in Bucharest in 1812, Russia received Bessarabia, and the Turkish Janissaries stopped systematically destroying the population of Serbia (which, by the way, they have been doing for the last 20 years). The previously planned trip to India as a continuation of the mission was wisely canceled, because it would have been too much.

Liberation from Napoleon

Another European maniac dreaming of taking over the world has appeared in France. He also turned out to be a very good commander and managed to conquer almost all of Europe. Guess who saved the European peoples from a cruel dictator again? After difficult battles on its territory with Napoleon’s army, which was superior in numbers and weapons, which relied on the combined military-industrial complex of almost all European powers, the Russian army went to liberate other peoples of Europe. In January 1813, Russian troops, pursuing Napoleon, crossed the Neman and entered Prussia. The liberation of Germany from the French occupation forces begins. On March 4, Russian troops liberated Berlin, on March 27 they occupied Dresden, and on March 18, with the assistance of Prussian partisans, they liberated Hamburg. On October 16-19, a general battle takes place near Leipzig, called the “Battle of the Nations,” the French troops are defeated by our army (with the participation of the pitiful remnants of the Austrian and Prussian armies). On March 31, 1814, Russian troops enter Paris.

Persia

July 1826 – January 1828: Russian-Persian War. On July 16, the Persian Shah, incited by England, without declaring war, sent troops across the Russian border to Karabakh and the Talysh Khanate. On September 13, near Ganja, Russian troops (8 thousand people) defeated the 35 thousand-strong army of Abbas Mirza and threw its remnants across the Araks River. In May, they launched an offensive in the Yerevan direction, occupied Etchmiadzin, blocked Yerevan, and then captured Nakhichevan and the Abbasabad fortress. Attempts by the Persian troops to push our troops away from Yerevan ended in failure, and on October 1 Yerevan was taken by storm. As a result of the Turkmanchay Peace Treaty, Northern Azerbaijan and Eastern Armenia were annexed to Russia, the population of which, hoping for salvation from complete destruction, actively supported Russian troops during military operations. The treaty, by the way, established for a year the right of free resettlement of Muslims to Persia, and Christians to Russia. For the Armenians, this meant the end of centuries of religious and national oppression.

Mistake #1 – Circassians

In 1828-1829, during the fourth Russian-Turkish war, Greece was liberated from the Turkish yoke. At the same time, the Russian Empire received only moral satisfaction from the good deed performed and many thanks from the Greeks. However, despite the victorious triumph, the diplomats made a very serious mistake, which will come back to haunt us more than once in the future. When concluding a peace treaty, the Ottoman Empire transferred the lands of the Circassians (Circassia) to Russia, while the parties to this agreement did not take into account the fact that the lands of the Circassians were not owned or under the authority of the Ottoman Empire. Adygs (or Circassians) is the general name of a single people, divided into Kabardians, Circassians, Ubykhs, Adygeis and Shapsugs, who, together with resettled Azerbaijanis, lived on the territory of what is now Dagestan. They refused to submit to secret agreements made without their consent, refused to recognize both the power of the Ottoman Empire and Russia over themselves, put up desperate military resistance to Russian aggression and were subdued by Russian troops only 15 years later. At the end of the Caucasian War, some of the Circassians and Abazas were forcibly resettled from the mountains to the foothill valleys, where they were told that those who wished could remain there only by accepting Russian citizenship. The rest were offered to move to Turkey within two and a half months. However, it was the Adygs, along with the Chechens, Azerbaijanis and other small Islamic peoples of the Caucasus, who caused the most problems for the Russian army, fighting as mercenaries first on the side of the Crimean Khanate and then the Ottoman Empire. In addition, the mountain tribes - Chechens, Lezgins, Azerbaijanis and Adygs - constantly committed attacks and atrocities in Georgia and Armenia protected by the Russian Empire. Therefore, we can say that on a global scale, without taking into account the principles of human rights (and then this was not accepted at all), this foreign policy mistake can not be counted. And the conquest of Derbent (Dagestan) and Baku (Baku Khanate, and later Azerbaijan) was due to the requirements of ensuring the security of Russia itself. But the disproportionate use of military force on the part of Russia, it must be admitted, still took place.

Mistake #2 – Invading Hungary

In 1848, Hungary tried to get rid of Austrian rule. After the Hungarian State Assembly refused to recognize Franz Joseph as the King of Hungary, the Austrian army invaded the country and quickly captured Bratislava and Buda. In 1849, the famous “spring campaign” of the Hungarian army took place, as a result of which the Austrians were defeated in several battles, and most of the territory of Hungary was liberated. On April 14, the Declaration of Independence of Hungary was adopted, the Habsburgs were deposed, and the Hungarian Lajos Kossuth was elected ruler of the country. But on May 21, the Austrian Empire signed the Warsaw Pact with Russia, and soon the Russian troops of Field Marshal Paskevich invaded Hungary. On August 9, it was defeated by the Russians near Temesvár, and Kossuth resigned. On August 13, the Hungarian troops of General Görgei capitulated. Hungary was occupied, repressions began, on October 6 Lajos Battyany was shot in Pest, 13 generals of the revolutionary army were executed in Arad. The revolution in Hungary was suppressed by Russia, which essentially turned into a mercenary of cruel colonists.

middle Asia

Back in 1717, individual Kazakh leaders, taking into account the real threat from external opponents, turned to Peter I with a request for citizenship. The emperor at that time did not dare to intervene in “Kazakh affairs.” According to Chokan Valikhanov: “... the first decade of the 18th century was a terrible time in the life of the Kazakh people. Dzungars, Volga Kalmyks, Yaik Cossacks and Bashkirs from different sides destroyed their uluses, drove away their cattle and took entire families captive.” From the east, the Dzungar Khanate posed a serious danger. From the south, the Kazakh Khanate was threatened by Khiva and Bukhara. In 1723, the Dzungar tribes once again attacked the weakened and scattered Kazakh zhuzes. This year went down in the history of the Kazakhs as a “great disaster.”

On February 19, 1731, Empress Anna Ioannovna signed a document on the voluntary entry of the Younger Zhuz into the Russian Empire. On October 10, 1731, Abulkhair and the majority of the elders of the Junior Zhuz entered into an agreement and took an oath about the inviolability of the agreement. In 1740, the Middle Zhuz came under Russian protection (protectorate). In 1741-1742, Dzungar troops again invaded the Middle and Junior Zhuzes, but the intervention of Russian border authorities forced them to retreat. Khan Ablai himself was captured by the Dzungars, but a year later he was released through the mediation of the Orenburg governor Neplyuev. In 1787, in order to save the population of the Younger Zhuz, who were being pressed by the Khivans, they were allowed to cross the Urals and roam to the Volga region. This decision was officially consolidated by Emperor Paul I in 1801, when the vassal Bukey (Internal) Horde, led by Sultan Bukey, was formed from 7,500 Kazakh families.

In 1818, the elders of the Senior Zhuz announced their entry under the protection of Russia. In 1839, in connection with the constant attacks of the Kokand people on the Kazakhs, Russian subjects, Russian military operations began in Central Asia. In 1850, an expedition was undertaken across the Ili River with the aim of destroying the Toychubek fortification, which served as a stronghold for the Kokand Khan, but it was captured only in 1851, and in 1854, the Vernoye fortification was built on the Almaty River (today Almatinka) and the entire Trans-Ili region entered into Russia. Let us note that Dzungaria was then a colony of China, forcibly annexed in the 18th century. But China itself, during the period of Russian expansion into the region, was weakened by the Opium War with Great Britain, France and the United States, as a result of which almost the entire population of the Middle Kingdom was subjected to forced drug addiction and ruin, and the government, in order to prevent total genocide, then urgently needed support from Russia. Therefore, the Qing rulers made small territorial concessions in Central Asia. In 1851, Russia concluded the Kulja Treaty with China, which established equal trade relations between the countries. Under the terms of the agreement, duty-free barter trade was opened in Gulja and Chuguchak, unhindered passage of Russian merchants to the Chinese side was ensured, and trading posts were created for Russian merchants.

On May 8, 1866, near Irjar, the first major clash between Russians and Bukharans took place, called the Battle of Irjar. This battle was won by Russian troops. Cut off from Bukhara, Khudoyar Khan accepted in 1868 a trade agreement proposed to him by Adjutant General von Kaufmann, according to which the Khivans pledged to stop raids and robberies of Russian villages, as well as to release captured Russian subjects. Also, under this agreement, Russians in the Kokand Khanate and Kokand residents in Russian possessions acquired the right to free stay and travel, establish caravanserais, and maintain trading agencies (caravan bashi). The terms of this agreement impressed me to the core - no seizure of resources, only the establishment of justice.

Finally, on January 25, 1884, a deputation of Mervians arrived in Askhabad and presented Governor-General Komarov with a petition addressed to the emperor to accept Merv as Russian citizenship and took the oath. The Turkestan campaigns completed the great mission of Rus', which first stopped the expansion of nomads into Europe, and with the completion of colonization, finally pacified the eastern lands. The arrival of Russian troops signaled the arrival of a better life. Russian general and topographer Ivan Blaramberg wrote: “The Kirghiz of Kuan Darya thanked me for liberating them from their enemies and destroying the robber nests.” Military historian Dmitry Fedorov put it more clearly: “Russian rule acquired enormous charm in Central Asia because it marked itself humane, peaceful attitude towards the natives and, having aroused the sympathy of the masses, was a desirable dominion for them.”

1853-1856: First Eastern War (or Crimean Campaign)

Here you can simply observe the quintessence of the cruelty and hypocrisy of our so-called “European partners.” Not only that, again we are seeing the painfully familiar to us from the history of the country friendly unification of almost all European countries in the hope of destroying more Russians and plundering Russian lands. We are already accustomed to this. But this time everything was done so openly, without even hiding behind false political reasons, that you are amazed. Russia had to wage the war against Turkey, England, France, Sardinia and Austria (which took a position of hostile neutrality). The Western powers, pursuing their economic and political interests in the Caucasus and the Balkans, persuaded Turkey to exterminate the southern peoples of Russia, assuring that, “if anything happens,” they will help. That “if anything” happened very quickly.

After the Turkish army invaded Russian Crimea and “slaughtered” 24 thousand innocent people, including more than 2 thousand small children (by the way, the children’s severed heads were then kindly given to their parents), the Russian army simply destroyed the Turkish , and the fleet was burned. In the Black Sea, near Sinop, Vice Admiral Nakhimov on December 18, 1853 destroyed the Turkish squadron of Osman Pasha. Following this, the united Anglo-French-Turkish squadron entered the Black Sea. In the Caucasus, the Russian army defeated the Turkish at Bayazet (July 17, 1854) and Kuryuk-Dar (July 24). In November 1855, Russian troops liberated Kars, inhabited by Armenians and Georgians (which we saved poor Armenians and Georgians over and over again at the cost of thousands of lives of our soldiers). On April 8, 1854, the allied Anglo-French fleet bombed the Odessa fortifications. On September 1, 1854, British, French and Turkish troops landed in Crimea. After a heroic 11-month defense, the Russians were forced to leave Sevastopol in August 1855. At the congress in Paris on March 18, 1856, peace was concluded. The conditions of this world are surprising in their idiocy: Russia lost the right to protect Christians in the Turkish Empire (let them slaughter, rape and dismember!) and pledged not to have either fortresses or a navy on the Black Sea. It doesn’t matter that the Turks massacred not only Russian Christians, but also French, English (for example, in Central Asia and the Middle East) and even German. The main thing is to weaken and kill the Russians.

1877-1878: another Russian-Turkish war (also known as the second Eastern War)

The Turks' oppression of Christian Slavs in Bosnia and Herzegovina sparked an uprising there in 1875. In 1876, the uprising in Bulgaria was pacified by the Turks with extreme cruelty, massacres of civilians were committed, and tens of thousands of Bulgarians were slaughtered. The Russian public was outraged by the massacre. On April 12, 1877, Russia declared war on Turkey. As a result, Sofia was liberated on December 23, and Adrianople was occupied on January 8. The path to Constantinople was open. However, in January, the English squadron entered the Dardanelles, threatening Russian troops, and in England a general mobilization was scheduled for the invasion of Russia. In Moscow, in order not to expose its soldiers and population to obvious masochism in a useless confrontation against almost the whole of Europe, they decided not to continue the offensive. But she still achieved protection for the innocent. On February 19, a peace treaty was signed in San Stefano, according to which Serbia, Montenegro and Romania were recognized as independent; Bulgaria, Bosnia and Herzegovina received autonomy. Russia received Ardahan, Lars, Batum (regions inhabited by Georgians and Armenians who had long been asking for Russian citizenship). The conditions of the San Stefano Peace caused a protest from England and Austria-Hungary (an empire that we had recently saved from collapse at the cost of the lives of our soldiers), who began preparations for war against Russia. Through the mediation of Emperor Wilhelm, a congress was convened in Berlin to revise the San Stefano Peace Treaty, which reduced Russia's successes to a minimum. It was decided to divide Bulgaria into two parts: a vassal principality and the Turkish province of Eastern Rumelia. Bosnia and Herzegovina was given over to Austria-Hungary.

Far Eastern expansion and mistake No. 3

In 1849, Grigory Nevelskoy began to explore the mouth of the Amur. Later, he establishes a winter quarters on the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk to trade with the local population. In 1855, the period of economic development of the uninhabited region began. In 1858, the Treaty of Aigun was concluded between the Russian Empire and Qing China, and in 1860, the Treaty of Beijing, which recognized Russian power over the Ussuri region, and in return the Russian government provided military assistance to China in the fight against Western invaders - diplomatic support and supplies weapons. If China at that time had not been so greatly weakened by the Opium War with the West, it would, of course, have competed with St. Petersburg and would not have allowed border territories to be developed so easily. But the foreign policy situation favored the peaceful and bloodless expansion of the Russian Empire in an eastern direction.

The rivalry between the Qing Empire and Japan for control of Korea in the 19th century came at great cost to the entire Korean people. But the saddest episode occurred in 1794-1795, when Japan invaded Korea and began real atrocities in order to intimidate the population and elite of the country and force them to accept Japanese citizenship. The Chinese army stood up to defend its colony and a bloody meat grinder began, in which, in addition to 70 thousand military personnel on both sides, a huge number of Korean civilians died. As a result, Japan won, transferred hostilities to Chinese territory, reached Beijing and forced the Qing rulers to sign the humiliating Treaty of Shimonoseki, according to which the Qing Empire ceded Taiwan, Korea and the Liaodong Peninsula to Japan, and also established trade preferences for Japanese merchants.

On April 23, 1895, Russia, Germany and France simultaneously appealed to the Japanese government demanding a refusal to annex the Liaodong Peninsula, which could lead to the establishment of Japanese control over Port Arthur and further aggressive expansion of the Japanese colonialists deeper into the continent. Japan was forced to agree. On May 5, 1895, Prime Minister Ito Hirobumi announced the withdrawal of Japanese troops from the Liaodong Peninsula. The last Japanese soldiers left for their homeland in December. Here Russia showed nobility - it forced the brutal aggressor to leave the occupied territory and helped prevent the spread of mass violence to new territories. A few months later, in 1896, Russia concluded an alliance treaty with China, according to which it received the right to build a railway through the territory of Manchuria; the treaty also established Russia’s protection of the Chinese population from possible Japanese aggression in the future. However, under the influence of the trade lobby, the government could not resist the temptation to exploit the weakness of its neighbor, exhausted by an unequal war, and “profit from it.”

In November 1897, German troops occupied Chinese Qingdao, and Germany forced China to give this region a long-term (99 years) lease. Opinions in the Russian government about the reaction to the capture of Qingdao were divided: Foreign Minister Muravyov and War Minister Vannovsky advocated taking advantage of the favorable moment to occupy the Chinese ports on the Yellow Sea of Port Arthur or Dalian Van. He argued this by the desirability for Russia of obtaining an ice-free port in the Pacific Ocean in the Far East. Finance Minister Witte spoke out against this, pointing out that “... from this fact (Germany’s seizure of Qingdao) ... in no way can one draw the conclusion that we must do exactly the same as Germany and also make a seizure from China. Moreover, such a conclusion cannot be drawn because China is not in an alliance with Germany, but we are in an alliance with China; we promised to defend China, and suddenly, instead of defending, we ourselves begin to seize its territory.”

Nicholas II supported Muravyov’s proposal, and on December 3 (15), 1897, Russian military ships stood in the Port Arthur roadstead. On March 15 (27), 1898, Russia and China signed the Russian-Chinese Convention in Beijing, according to which Russia was given the ports of Port Arthur (Lushun) and Dalniy (Dalian) with adjacent territories and waters for lease use for 25 years and the construction of to these ports by railway (South Manchurian Railway) from one of the points of the Chinese Eastern Railway.

Yes, our country did not undertake any violence to solve its economic and geopolitical problems. But this episode of Russian foreign policy was unfair to China, an ally whom we actually betrayed and, with our behavior, became like Western colonial elites who would stop at nothing to make money. In addition, by these actions the tsarist government created an evil and vengeful enemy for its country. After all, the realization that Russia had actually taken the Liaodong Peninsula from Japan, captured during the war, led to a new wave of militarization of Japan, this time directed against Russia, under the slogan “Gashin-shotan” (Japanese: “sleeping on a board with nails”), calling on the nation to endure tax increases for the sake of military revenge in the future. As we remember, this revenge would be undertaken by Japan quite soon - in 1904.

Conclusion

Continuing its global mission to protect oppressed small peoples from enslavement and destruction, as well as defending its own sovereignty, in the 19th century Russia nevertheless made gross foreign policy mistakes, which will certainly affect the image of its perception among a number of neighboring ethnic groups for many years. The savage and completely inexplicable invasion of Hungary in 1849 would in the future become the cause of distrust and hostile wariness of that nation towards Russian identity. As a result, it became the second European nation “offended” by the Russian Empire (after Poland). And the brutal conquest of the Circassians in the 20-40s, despite the fact that it was provoked, is also difficult to justify. Largely thanks to this, the North Caucasus today is the largest and most complex region in the federal structure of interethnic relations. Although bloodless, but still an unpleasant fact of history, it was the hypocritical and treacherous behavior of the St. Petersburg imperial court towards allied China during the Second Opium War. At that time, the Qing Empire was fighting against an entire Western civilization that had actually turned into a huge drug cartel. It is also worth noting that the Russian establishment, naturally “attracted” to enlightened Europe, in the 19th century continues to try to integrate the country into the halo of influence of Western civilization, strives to become “one of its own” for it, but receives even more cruel lessons of European hypocrisy than before.

Along with the collapse of the Russian Empire, the majority of the population chose to create independent national states. Many of them were never destined to remain sovereign, and they became part of the USSR. Others were incorporated into the Soviet state later. What was the Russian Empire like at the beginning? XXcentury?

By the end of the 19th century, the territory of the Russian Empire was 22.4 million km 2. According to the 1897 census, the population was 128.2 million people, including the population of European Russia - 93.4 million people; Kingdom of Poland - 9.5 million, - 2.6 million, Caucasus Territory - 9.3 million, Siberia - 5.8 million, Central Asia - 7.7 million people. Over 100 peoples lived; 57% of the population were non-Russian peoples. The territory of the Russian Empire in 1914 was divided into 81 provinces and 20 regions; there were 931 cities. Some provinces and regions were united into governorates-general (Warsaw, Irkutsk, Kiev, Moscow, Amur, Stepnoe, Turkestan and Finland).

By 1914, the length of the territory of the Russian Empire was 4383.2 versts (4675.9 km) from north to south and 10,060 versts (10,732.3 km) from east to west. The total length of the land and sea borders is 64,909.5 versts (69,245 km), of which the land borders accounted for 18,639.5 versts (19,941.5 km), and the sea borders accounted for about 46,270 versts (49,360 .4 km).

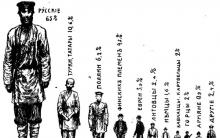

The entire population was considered subjects of the Russian Empire, the male population (from 20 years old) swore allegiance to the emperor. The subjects of the Russian Empire were divided into four estates (“states”): nobility, clergy, urban and rural inhabitants. The local population of Kazakhstan, Siberia and a number of other regions were distinguished into an independent “state” (foreigners). The coat of arms of the Russian Empire was a double-headed eagle with royal regalia; the state flag is a cloth with white, blue and red horizontal stripes; The national anthem is “God Save the Tsar.” National language - Russian.

Administratively, the Russian Empire by 1914 was divided into 78 provinces, 21 regions and 2 independent districts. The provinces and regions were divided into 777 counties and districts and in Finland - into 51 parishes. Counties, districts and parishes, in turn, were divided into camps, departments and sections (2523 in total), as well as 274 landmanships in Finland.

Territories that were important in military-political terms (metropolitan and border) were united into viceroyalties and general governorships. Some cities were allocated into special administrative units - city governments.

Even before the transformation of the Grand Duchy of Moscow into the Russian Kingdom in 1547, at the beginning of the 16th century, Russian expansion began to expand beyond its ethnic territory and began to absorb the following territories (the table does not include lands lost before the beginning of the 19th century):

|

Territory |

Date (year) of accession to the Russian Empire |

Data |

|

Western Armenia (Asia Minor) |

The territory was ceded in 1917-1918 |

|

|

Eastern Galicia, Bukovina (Eastern Europe) |

ceded in 1915, partially recaptured in 1916, lost in 1917 |

|

|

Uriankhai region (Southern Siberia) |

Currently part of the Republic of Tuva |

|

|

Franz Josef Land, Emperor Nicholas II Land, New Siberian Islands (Arctic) |

The archipelagos of the Arctic Ocean are designated as Russian territory by a note from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs |

|

|

Northern Iran (Middle East) |

Lost as a result of revolutionary events and the Russian Civil War. Currently owned by the State of Iran |

|

|

Concession in Tianjin |

Lost in 1920. Currently a city directly under the People's Republic of China |

|

|

Kwantung Peninsula (Far East) |

Lost as a result of defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. Currently Liaoning Province, China |

|

|

Badakhshan (Central Asia) |

Currently, Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Okrug of Tajikistan |

|

|

Concession in Hankou (Wuhan, East Asia) |

Currently Hubei Province, China |

|

|

Transcaspian region (Central Asia) |

Currently belongs to Turkmenistan |

|

|

Adjarian and Kars-Childyr sanjaks (Transcaucasia) |

In 1921 they were ceded to Turkey. Currently Adjara Autonomous Okrug of Georgia; silts of Kars and Ardahan in Turkey |

|

|

Bayazit (Dogubayazit) sanjak (Transcaucasia) |

In the same year, 1878, it was ceded to Turkey following the results of the Berlin Congress. |

|

|

Principality of Bulgaria, Eastern Rumelia, Adrianople Sanjak (Balkans) |

Abolished following the results of the Berlin Congress in 1879. Currently Bulgaria, Marmara region of Turkey |

|

|

Khanate of Kokand (Central Asia) |

Currently Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan |

|

|

Khiva (Khorezm) Khanate (Central Asia) |

Currently Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan |

|

|

including Åland Islands |

Currently Finland, the Republic of Karelia, Murmansk, Leningrad regions |

|

|

Tarnopol District of Austria (Eastern Europe) |

Currently, Ternopil region of Ukraine |

|

|

Bialystok District of Prussia (Eastern Europe) |

Currently Podlaskie Voivodeship of Poland |

|

|

Ganja (1804), Karabakh (1805), Sheki (1805), Shirvan (1805), Baku (1806), Kuba (1806), Derbent (1806), northern part of the Talysh (1809) Khanate (Transcaucasia) |

Vassal khanates of Persia, capture and voluntary entry. Secured in 1813 by a treaty with Persia following the war. Limited autonomy until the 1840s. Currently Azerbaijan, Nagorno-Karabakh Republic |

|

|

Imeretian kingdom (1810), Megrelian (1803) and Gurian (1804) principalities (Transcaucasia) |

Kingdom and principalities of Western Georgia (independent from Turkey since 1774). Protectorates and voluntary entries. Secured in 1812 by a treaty with Turkey and in 1813 by a treaty with Persia. Self-government until the end of the 1860s. Currently Georgia, Samegrelo-Upper Svaneti, Guria, Imereti, Samtskhe-Javakheti |

|

|

Minsk, Kiev, Bratslav, eastern parts of Vilna, Novogrudok, Berestey, Volyn and Podolsk voivodeships of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Eastern Europe) |

Currently, Vitebsk, Minsk, Gomel regions of Belarus; Rivne, Khmelnitsky, Zhytomyr, Vinnitsa, Kiev, Cherkassy, Kirovograd regions of Ukraine |

|

|

Crimea, Edisan, Dzhambayluk, Yedishkul, Little Nogai Horde (Kuban, Taman) (Northern Black Sea region) |

Khanate (independent from Turkey since 1772) and nomadic Nogai tribal unions. Annexation, secured in 1792 by treaty as a result of the war. Currently Rostov region, Krasnodar region, Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol; Zaporozhye, Kherson, Nikolaev, Odessa regions of Ukraine |

|

|

Kuril Islands (Far East) |

Tribal unions of the Ainu, bringing into Russian citizenship, finally by 1782. According to the treaty of 1855, the Southern Kuril Islands are in Japan, according to the treaty of 1875 - all the islands. Currently, the North Kuril, Kuril and South Kuril urban districts of the Sakhalin region |

|

|

Chukotka (Far East) |

Currently Chukotka Autonomous Okrug |

|

|

Tarkov Shamkhaldom (North Caucasus) |

Currently the Republic of Dagestan |

|

|

Ossetia (Caucasus) |

Currently the Republic of North Ossetia - Alania, the Republic of South Ossetia |

|

|

Big and Small Kabarda |

Principalities. In 1552-1570, a military alliance with the Russian state, later vassals of Turkey. In 1739-1774, according to the agreement, it became a buffer principality. Since 1774 in Russian citizenship. Currently Stavropol Territory, Kabardino-Balkarian Republic, Chechen Republic |

|

|

Inflyantskoe, Mstislavskoe, large parts of Polotsk, Vitebsk voivodeships of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Eastern Europe) |

Currently, Vitebsk, Mogilev, Gomel regions of Belarus, Daugavpils region of Latvia, Pskov, Smolensk regions of Russia |

|

|

Kerch, Yenikale, Kinburn (Northern Black Sea region) |

Fortresses, from the Crimean Khanate by agreement. Recognized by Turkey in 1774 by treaty as a result of war. The Crimean Khanate gained independence from the Ottoman Empire under the patronage of Russia. Currently, the urban district of Kerch of the Republic of Crimea of Russia, Ochakovsky district of the Nikolaev region of Ukraine |

|

|

Ingushetia (North Caucasus) |

Currently the Republic of Ingushetia |

|

|

Altai (Southern Siberia) |

Currently, the Altai Territory, the Altai Republic, the Novosibirsk, Kemerovo, and Tomsk regions of Russia, the East Kazakhstan region of Kazakhstan |

|

|

Kymenygard and Neyshlot fiefs - Neyshlot, Vilmanstrand and Friedrichsgam (Baltics) |

Flax, from Sweden by treaty as a result of the war. Since 1809 in the Russian Grand Duchy of Finland. Currently Leningrad region of Russia, Finland (region of South Karelia) |

|

|

Junior Zhuz (Central Asia) |

Currently, the West Kazakhstan region of Kazakhstan |

|

|

(Kyrgyz land, etc.) (Southern Siberia) |

Currently the Republic of Khakassia |

|

|

Novaya Zemlya, Taimyr, Kamchatka, Commander Islands (Arctic, Far East) |

Currently Arkhangelsk region, Kamchatka, Krasnoyarsk territories |

In the 19th century, Russia was one of the strongest world powers, but as before, it lagged significantly behind advanced Western countries in development. This, among other things, served as a source of multiple internal Russian contradictions caused by the successes of France under the leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte, as well as the expansion of the ideas of the great French revolution.

The most important event of the 19th century in Russia, without a doubt, is considered one of the most difficult wars - the war with Napoleonic France as part of the anti-Napoleonic coalition, as a result of which the French army, at the cost of burning Moscow after the Battle of Borodino, was turned back by Russian troops. Also, during the reign of Alexander I, in addition to the war with France, the Russian Empire also fought successful battles with Turkey and Sweden.

One of the largest events of the century is the Decembrist Uprising, which occurred in December 1825. The uprising was indirectly related to the public abdication of the direct heir to the throne of Alexander I, Constantine, in favor of his brother, Nicholas. Over the course of two days - December 13 and 14, on the square near the Senate building, a group of conspirators (northern, southern society) gathered several thousand soldiers. The conspirators were going to read out the revolutionary “Manifesto to the Russian People,” which, in their plans, personified the destruction of absolutist political institutions in Russia, the proclamation of civil democratic freedoms, and the transfer of power to a provisional government.

However, the leaders of the uprising did not have the fortitude to begin military operations against the imperial army, and the leader of the uprising, Prince Trubetskoy, did not appear on the square at all, so the revolutionary forces were soon dispersed, and Nicholas took the imperial title.

The next ruler, after Alexander, is Nicholas I. Russia at this moment is in a difficult economic and social situation, so the emperor is forced to wage numerous wars of conquest - this leads to a number of serious conflicts with world powers, especially with Turkey, which ultimately culminates in the Crimean War of 1853, as a result of which Russia was defeated by a coalition of the Ottoman, British and French empires.

In 1855, Alexander II came to power. He reduces the length of military service from 20 years to 6, reforms the judicial and zemstvo systems, and also abolishes serfdom, thanks to which he is popularly called the “tsar liberator.”

After the murder of Alexander 2 as a result of another assassination attempt, his heir, Alexander III, sits on the throne. He decides that the murder of his father occurred due to dissatisfaction with his reform activities, so he relies on reducing the number of reforms being carried out, as well as military conflicts (during the 13 years of his reign, Russia did not participate in a single military conflict, for which Alexander III was nicknamed the peacemaker). Alexander III reduces taxes and tries to develop industry in the country as much as possible. Also, this ruler

signs a peace treaty with France and includes the territories of Central Asia into the empire.

Alexander 3 appoints Sergei Witte to the post of Minister of Finance, as a result of which the previously implemented policy of exporting bread as the basis for boosting the economy was canceled. The national currency was backed by gold, which increased the volume of foreign investment in the country and became the key to a sharp rise in the economy and the gradual industrialization of the country.

During the period of economic growth, Emperor Nicholas II came to power, remembered in history as the “rag tsar”, who made a number of failed decisions, including the notorious Russo-Japanese War, the defeat of which indirectly led to the emergence of the seeds of revolution in the country.