creativity - to the psychological mechanism of creative activity, to its experimental analysis.

Here the central link of the psychological mechanism of creativity is identified and analyzed. It implements the general principle of development already mentioned earlier and discussed in detail in the first part of the book. It is discovered that this link itself is represented by a hierarchy of structural levels of its organization. In many different experiments, one and the same fact persistently emerges: the need for development arises at the highest level, the means to satisfy it are formed at the lower levels; By being included in the functioning of a higher level, they transform the way of this functioning. Psychologically, satisfying the need for novelty and development is always based on a special form of intuition. In scientific and technical creativity, the effect of an intuitive solution is also verbalized and sometimes formalized. Following the general characteristics of the central link, materials from an experimental study of psychological models of its main components - intuition, verbalization and formalization - are presented. Then other elements of the psychological mechanism of creativity are identified and analyzed, related to the general and specific abilities of people, the qualities of a creative personality, and a wide range of conditions for the effectiveness of creative work. All these elements are identified and considered as conditions conducive to the effective operation of the central link of the psychological mechanism of creativity.

The entire system of concepts of the psychology of creativity presented in the book and its internal logic are built on this same basis.

PART I

METHODOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

CHAPTER 1

THE NATURE OF CREATIVITY

Creativity as a mechanism of development

When characterizing the state of the problem of the nature of creativity, one should first of all emphasize the understanding of creativity in the broad and narrow sense, long established in the literature.

It can be found in the article “Creativity”, included in the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, written by F. Batyushkov (the broad sense is called “direct” in it, the narrow sense - “generally accepted”): “Creativity - in the literal sense - is the creation of something new. In this meaning, this word could be applied to all processes of organic and inorganic life, for life is a series of continuous changes and everything that is renewed and everything that arises in nature is a product of creative forces. But the concept of creativity presupposes a personal beginning and the corresponding word is used primarily in relation to human activity. In this generally accepted sense, creativity is a conventional term for designating a mental act expressed in the embodiment, reproduction or combination of data from our consciousness, in a (relatively) new form, in the field of abstract thought, artistic and practical activity (T. scientific, T. poetic, musical , T. in the fine arts, T. administrator, commander, etc.” (Batyushkov, 1901).

In the early period of research, a certain amount of attention was paid to the broad meaning of creativity. However, in a later period, the view of the nature of creativity changed dramatically. The understanding of creativity, both in our country and in foreign literature, has been reduced exclusively to its narrow meaning."

In relation to this narrow meaning, modern studies of the criteria of creative activity are being conducted (especially numerous abroad (Bernstein, 1966).

1 For more details, see: Ponomarev Ya. A. Development of problems of scientific creativity in Soviet psychology. - “Problems of scientific creativity in modern psychology:”. M., 1971.

11

Most modern foreign scientists involved in issues of scientific creativity unanimously believe that a lot of work has been done in the area of creativity criteria, but the desired results have not yet been obtained. For example, the authors of many studies conducted in recent decades in the United States tend to share Gieselin's point of view, according to which the definition of the difference between creative and non-creative activities remains completely subjective.

The complexity of the structure of creativity prompts researchers to think about the need for multiple criteria. However, an empirical search for such criteria leads to insignificant results. Put forward criteria such as “popularity”, “productivity” (Smith, Taylor, Ghiselin), “the degree of reconstruction of the understanding of the universe” (Ghiselin), “the breadth of influence of the scientist’s activities on various fields of scientific knowledge” (Lachlen), “the degree of novelty of ideas, approaches, solutions” (Sprecher, Stein), “social value of scientific products” (Brogden) and many others remain unconvincing2. S. M. Bernstein (1966) rightly sees this as a consequence of a completely unsatisfactory level of development of theoretical issues in the study of creativity.

It must be especially emphasized that the question of creativity criteria is far from idle. Sometimes the wrong approach to its consideration becomes a serious obstacle to the study of creativity, shifting its subject. For example, the founders of heuristic programming, Newell, Shaw, and Simon (1965), taking advantage of the uncertainty of the criteria that distinguish a creative thought process from a non-creative one, put forward the position that the theory of creative thinking is a theory of solving cognitive problems with modern electronic computing devices. They emphasize that the validity of their claims to a theory of creative thinking depends on how broadly or narrowly the term “creative” is interpreted. “If we are to view all complex problem-solving activity as creative, then, as we will show, successful programs for mechanisms that imitate a human problem solver already exist, and a number of their characteristics are known. If we reserve the term “creative” for activities like discovering a specialty,

3 It should be noted that all those particular criteria that relate to the characteristics of creativity in the narrow sense (as one of the forms of human activity) and which are now varied from different perspectives by most modern researchers, were already outlined in the works of domestic researchers of the early period (novelty, originality, departure from the template, breaking traditions, surprise, expediency, value, etc.). This indicates the stagnation of thought in this area (for more details, see: Ponomarev #. A. Development of problems of scientific creativity" in Soviet psychology).

12

tional theory of relativity or the creation of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony, then there are currently no examples of creative mechanisms."

The authors adopt the first version for practical guidance - hence their theory of creative thinking.

Of course, such a position raises sharp objections, for example, in the spirit of the statement of L. N. Landa (1967), who showed that modern heuristic programs are only “incomplete algorithms” and emphasized that heuristic programming does not characterize creative processes. Creativity lies not in that activity, each link of which is completely regulated in advance by given rules, but in that, the preliminary regulation of which contains a certain degree of uncertainty, in activity that brings new information, presupposing self-organization.

Other objections can be raised. For example, if we agree with the approach of Newell, Shaw and Simon, we will find ourselves in a very peculiar position: our studies of creativity will not be directed towards a pre-designated object, but this object itself will be what the work done will lead to. In some situations such assumptions are probably possible. But in this case, the settings of heuristic programming are rejected and the characteristics of creativity that appear quite sharply in many empirical studies, although still poorly disclosed, are ignored. After all, one can rightfully make another decision: the class of problems whose solutions are accessible to machine modeling is not included in the class of creative ones; the latter can only include those whose solutions are fundamentally not amenable to modern machine modeling. Moreover, the impossibility of simulating solutions to such problems using modern computers can be one of the fairly clear practical criteria for true creativity.

Newell, Shaw and Simon, of course, clearly understand and foresee the possibility of such a version. But they think it can be ignored. Such confidence is supported by a calculation of the precariousness of the existing criteria that distinguish a creative thought process from a non-creative one3; it is reinforced by the conviction that it is impossible to identify satisfactory objective criteria for creativity. All this is a direct consequence of the lack of proper support for generalized, regulating methodological principles that determine the preliminary orientation in particular research, and, moreover, the lack of

3 Newell, Shaw and Simon define creative activity as a type of activity for solving special problems that are characterized by novelty, originality, stability and difficulty in formulating the problem (“Psychology of Thinking”. Collection of translations from German and English. Edited by A. M. Matyushkin . M., 1965).

The book examines the subject and methods of the psychology of creativity, the central link in the psychological mechanism of creative activity, the abilities and qualities of a creative personality.

It contains extensive experimental material, on the basis of which a number of psychological laws of creative activity and laws of the formation of conditions favorable to it are formulated.

About the author: Ponomarev Yakov Aleksandrovich (12/25/1920, Vichuga, Ivanovo region - 02/22/1997) - a leading scientist in the field of psychology of creativity and intelligence, psychology methodology, a high-class professional, Doctor of Psychology, professor, chief researcher at the Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, honored... more...

Also read with the book “Psychology of Creativity”:

Preview of the book “Psychology of Creativity”

USSR ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

INSTITUTE OF PSYCHOLOGY

Y. A. PONOMAREV

PSYCHOLOGY OF CREATIVITY

PUBLISHING HOUSE "SCIENCE> MOSCOW 1976

The book examines the subject and methods of the psychology of creativity, the central link in the psychological mechanism of creative activity, the abilities and qualities of a creative personality. It contains extensive experimental material, on the basis of which a number of psychological laws of creative activity and laws of the formation of conditions favorable to it are formulated.

The book is addressed to psychologists, philosophers and a wide range of readers interested in problems of creativity.

n 10508-069 „. ?6 042 (02)-76

© Nauka Publishing House, 1976

INTRODUCTION

RESEARCH OF CREATIVITY IN CONDITIONS OF SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL REVOLUTION

The psychology of creativity - a field of knowledge that studies the creation of new, original things by a person in various fields of activity, primarily in science, technology, and art - came up in the middle of the 20th century. to a new stage of its development. Particularly dramatic changes have occurred in the psychology of scientific creativity: its authority has increased, its content has become deeper. It has taken a dominant place in creativity research.

The conditions for a new stage in the development of the psychology of scientific creativity arose in the situation of the scientific and technological revolution, which significantly changed the type of social stimulation of activity research in science.

For a long time, society did not have an acute practical need for the psychology of creativity, including scientific creativity. Talented scientists appeared as if by themselves; they spontaneously made discoveries, satisfying the pace of development of society, in particular science itself. The main social incentive for improving the psychology of creativity remained curiosity, which sometimes mistook a little controlled invention, a game of fantasy, for a perfect product of scientific research.

The lightness of the criteria for assessing the quality of research in the psychology of creativity was also imposed by its historical traditions. Most of the pioneers of creativity research were idealistic thinkers. They saw in creativity the most fully expressed freedom of manifestation of the human spirit, not amenable to scientific analysis. The idea of purposefully increasing the efficiency of creating new, original, socially significant values was considered as empty fun. The existence of objective laws of human creativity was actually denied. The main task of creativity researchers was to describe the circumstances surrounding creative activity. Legends were collected that sparked the curiosity of gullible readers. Even the most conscientious

Well-known and valuable works did not go further than stating the facts lying on the surface of events.

All these studies have been collected over the centuries under the common banner of “creativity theory.” Since the last decades of the 19th century. they began to be referred to as the “psychology of creativity.” Psychology was then understood as the science of the soul, of ideal spiritual activity.

A rough idea of the nature of the “theory and psychology of creativity” at the beginning of the 20th century. can be made, for example, based on the materials of value judgments relating to this area of knowledge and given in the works themselves on the “theory and psychology of creativity”, in other words, based on the impression of observers who consider their science from within itself.

Some authors of that time did not dare to classify the theory of creativity and the psychology embedded in it as a scientific discipline. From their point of view, it is rather a tendentious grouping of fragmentary facts and random empirical generalizations, snatched without any method, without any system or connection from the fields of physiology of the nervous system, neuropathology, history of literature and art. These fragmentary facts and random empirical data are accompanied by a number of risky comparisons and hasty generalizations of data from aesthetics and literature, and at the same time a number of more or less subtle observations, introspections, supported by references to the autobiographical self-confession of poets, artists, and thinkers.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, after research into artistic and scientific-philosophical creativity, research into natural science creativity appeared, and somewhat later, into technical creativity. They delineated the subject of research more strictly. This had a beneficial effect on the productivity of creativity learning. Some circumstances common to all types of creativity have emerged. Attention began to focus on more significant phenomena.

However, the principles of creativity research have largely changed little. This happened not only because the subject of research was indeed very complex, but mainly because until the middle of our century, the study of creativity was not given significant importance.

In the middle of the 20th century. curiosity, which stimulated the development of knowledge about creativity, lost its monopoly. A clearly expressed need for rational management of creative activity has arisen - the type of social order has changed dramatically.

Emphasizing this sharp change in the type of social order, let us draw attention to the following circumstance: the new need of society was not generated by the internal development of the psychology of creativity - it was not this area of knowledge that indicated to society

4

possibility and feasibility of creativity management. The shift in social stimulation was caused by the scientific and technological revolution - a qualitative leap in the development of productive forces, which turned science into a direct productive force, making the economy significantly dependent on the achievements of science.

In recent years, our scientific literature has shown conditions conducive to the intensification of research into the psychology of creativity. The complexity of the problems that science has approached to solve, the ever-increasing provision of scientific research with the latest technical means are closely related to changes in the structure of the organization of this research, the emergence of new organizational units - scientific teams, the transformation of scientific work into a mass profession, etc. The age of handicraft in science is gone to the past. Science has become a complexly organized system that requires special research to consciously manage the course of scientific progress.

Research on creativity is of particular importance. Life presents researchers in this area with a complex of practical problems. These tasks are generated by the fact that the pace of development of science cannot be constantly increased only by increasing the number of people involved in it. We must constantly increase the creative potential of scientists. To do this, it is necessary to purposefully form creative scientists, carry out rational selection of personnel, create the most favorable motivation for creative activity, find means that stimulate the successful course of the creative act, rationally use modern possibilities for automating mental work, approach the optimal organization of creative teams, etc.

The old type of knowledge, stimulated by curiosity - mainly the contemplative-explanatory type - could not, of course, satisfy the new need of society, cope with the new social order - to ensure rational management of creativity. There had to be a change in the type of knowledge, a new type had to emerge—effectively transformative. Has such a change occurred?

Let us take a look from this point of view at the modern psychology of scientific creativity in the USA, where research in this area is currently most intensive.

In 1950, one of the leading psychologists in the US-D. Guilford appealed to his colleagues in the association to expand research on the psychology of creativity in every possible way. The call met with a corresponding response. Many publications have appeared under the heading of the psychology of creativity. They covered, it would seem, all the traditional problems of this field of knowledge: questions of criteria for creative activity and its difference from non-creative activity, the nature of creativity, patterns

5

the creative process, the specific characteristics of a creative personality, the development of creative abilities, the organization and stimulation of creative activity, the formation of creative teams, etc. However, as it became clear, the scientific value of this stream of publications is small. And first of all, because the acceleration of this kind of research by US scientists occurred despite the obvious unpreparedness of the theory.

Modern psychology of scientific creativity in the United States is narrowly utilitarian. At the cost of expensive, unproductive efforts, she tries to obtain direct answers to the practical problems put forward by life. Sometimes US psychologists, relying on “common sense”, vast empirical material and its processing using modern mathematics, manage to offer solutions to certain practical problems. However, such successes are palliative. It is important to note that the vast majority of such tasks are not strictly psychological. Rather, these are “common sense” tasks. Their solutions are of a narrowly applied nature and are confined to purely specific situations. The mechanisms of the phenomena being studied are not revealed, and therefore their invariants are not revealed. Some modifications of specific conditions make previously obtained solutions no longer suitable and require new empirical research.

Excessive enthusiasm for superficial analysis is fraught with obvious danger, especially when it is associated with an appeal to social objects, the external appearance of which is easily accessible to direct observation, while their internal structure is diverse and extremely complex. Superficial work at first often achieves a certain success, successfully using some of the previously accumulated valuable knowledge. This creates a certain authority for the emerging direction. It becomes recognized and popular. Then follows an idle move, which already interferes with the development of full-fledged research, veiling its true problems and real difficulties, creating the appearance of satisfying practical needs.

An analysis of the psychology of scientific creativity in the United States shows that the scientific and technological revolution took creativity research by surprise. There was no accumulated knowledge that could be called fundamental. The ideas contained in these studies were already put forward in general terms before the 40s of our century.

There is no reason to think that the ideas and principles already known by this time correspond to the new social incentive; we do not have sufficiently convincing facts about the rational management of scientific creativity.

Therefore, as the most important characteristic of the modern situation in the field of research into problems of creativity, we must name the contradiction consisting in the inconsistency of what has been achieved

6

the level of knowledge and the social need for it, i.e., in the discrepancy between the type of social order and the type of knowledge achieved - in the lag between the type of knowledge and the type of order.

Of great importance for finding ways to overcome this contradiction is the analysis of trends in the historical development of the psychology of creativity. A general idea of the genesis of the ideas of modern creativity psychology can be successfully built on the material of domestic science. The author of “The History of Soviet Psychology” A.V. Petrovsky (1967), characterizing Russian psychology at the beginning of the 20th century, emphasizes that it “represented one of the detachments of European psychological science. The research of domestic scientists devoted to individual psychological problems cannot be considered in isolation from the corresponding works of their foreign colleagues, whose ideas they developed or refuted, whose influence they experienced or which they themselves influenced.” Everything said here fully applies to the psychology of creativity. Therefore, consideration of its problems in Russian science reveals to us not only the own positions of domestic authors, but also makes it possible to get an idea of the state of the psychology of creativity of that time abroad. In general, the same can be applied to Soviet psychological science. At the same time, after the victory of the Great October Socialist Revolution, deep fundamental changes occurred in the development of psychological thought in the USSR: a gradual rethinking of psychological research began on the basis of dialectical-materialist methodology, which gave an extremely valuable and essential originality to our research and freed many scientists from idealistic wanderings.

The genesis of the ideas of the psychology of creativity, the features of the general approach to research, the dynamics of transformations of this approach and the trend of its strategic direction were traced by the author in the work “Development of problems of scientific creativity in Soviet psychology” (1971), which also included the pre-October period. It examines the works of the pioneers of the emerging study of the psychology of creativity in Russia - followers of the philosophical and linguistic concept of A. A. Potebnya - D. N. Ovsyaniko-Kulikovsky (1902, etc.) and his student B. A. Lezin (compiler and editor of the collections “Questions theory and psychology of creativity", the main tribune of Potebni-stov), works by P. K. Engelmeyer, M. A. Bloch, I. I. Lapshin, S. O. Gruzenberg, V. M. Bekhterev, V. V. Savich, F. Yu. Levinson-Lessing, V. L. Omelyansky, I. N. Dyakov, N. V. Petrovsky and P. A. Rudik, A. P. Nechaev, P. M. Yakobson,

V. P. Polonsky, S. L. Rubinshtein, B. M. Teplov, A. N. Leontyev, I. S. Sumbaeva, B. M. Kedrova, Ya. A. Ponomarev,

S. M. Vasileisky, G. S. Altshuller, V. N. Pushkin,

7

M. S. Bernshtein, O. K. Tikhomirov, M. G. Yaroshevsky, V. P. Zinchenko and others.

The results of our earlier analysis of the development of problems of scientific creativity in Soviet psychology are used by us in many sections of this book. Here we will only point out the main trend of changes in the general approach to creativity research.

This tendency is expressed in a gradual movement from an undifferentiated, syncretic description of the phenomena of creativity, from attempts to directly embrace these phenomena in all their concrete integrity to the development of an idea of the study of creativity as a complex problem - in movement along the line of differentiation of aspects, identifying a number of different the nature of the laws that determine creativity.

Let us also note that today such differentiation is still far from complete.

Our domestic scientists have made a very important contribution to the study of the psychology of creativity. Great and varied interest in this area of knowledge is characteristic of the first days after October. It survived until the mid-30s, but then declined and almost disappeared. Currently, the curve of this interest has risen sharply again.

Despite some pause in the study of the psychology of creativity, we have significant advantages over bourgeois scientists: our psychological research, based on the most progressive Marxist-Leninist methodology in the world, has brought us significantly closer to turning the psychology of creativity into effectively transformative knowledge. In contrast to “psychological and sociological” studies of increasing the efficiency of creative work in science, conducted at the level of “common sense,” we pay main attention to the analysis of the theoretical foundation of the psychology of creativity, identifying and overcoming theoretical difficulties.

It is customary to begin the presentation of any field of knowledge with a description of its subject. But we do not have such an opportunity.

At the level of a formal scheme, in the most general terms, the subject of the psychology of creativity can be considered as a zone of intersection of two circles, one of which symbolizes knowledge about creativity, the other - psychology. However, the area of reality that this scheme should reflect still does not have clearly defined, generally accepted boundaries, which is primarily due to the level of understanding of the nature of creativity, on the one hand, and the nature of the psyche, on the other.

8

The lag in the level of understanding of the nature of creativity from the requirements of modern tasks in the study of creative activity is clearly revealed even in the most elementary, as it may seem at first glance, provisions, for example, in the question of criteria for creativity, criteria for creative activity. Despite the fact that this issue has acquired enormous practical significance in recent years, the lack of sufficiently strict criteria for determining the difference between creative and non-creative human activity is now generally recognized. At the same time, it is obvious that without such criteria it is impossible to identify with sufficient certainty the subject of research itself. It is also obvious that the concepts of the criteria of creativity and its nature, essence are closely interconnected - these are two sides of the same problem.

The insufficient development of the question of the nature of the psyche follows from the fact that in our psychology there is still no generally accepted approach to understanding this nature. The psychic is usually understood as something concrete. The struggle between two mutually exclusive positions concerning its most general, fundamental characteristics continues. One of these positions considers the psychic to be ideal (immaterial), the other asserts its materiality.

All of the above shows with sufficient conviction that the current state of knowledge in the psychology of creativity categorically requires that further research be preceded by a special consideration of the main components of this science. The question of the subject of the psychology of creativity turns into a problem requiring a methodological solution. The first part of the book is devoted to this problem. Creativity in a broad sense is considered here as a mechanism of development, as an interaction leading to development; human creativity is one of the specific forms of manifestation of this mechanism. The approach to the study of this particular form is based on the principle of transforming the stages of development of a phenomenon into structural levels of its organization and functional stages of further developmental interactions. From the position of this principle, a strategy for a comprehensive - analytical-synthetic - study of creative activity is being developed. The criteria for identifying analytical complexes are the structural levels of organization of a given specific form of creativity. Analysis of the place of psychology in the system of an integrated approach leads to the idea of the mental as one of the structural levels of the organization of life. With this understanding, the subject of the psychology of creativity becomes the mental structural level of the organization of creative activity.

In the second part of the book, based on the solution obtained, we turn to the internal problems of psychology itself.

creativity - to the psychological mechanism of creative activity, to its experimental analysis.

Here the central link of the psychological mechanism of creativity is identified and analyzed. It implements the general principle of development already mentioned earlier and discussed in detail in the first part of the book. It is discovered that this link itself is represented by a hierarchy of structural levels of its organization. In many different experiments, one and the same fact persistently emerges: the need for development arises at the highest level, the means to satisfy it are formed at the lower levels; By being included in the functioning of a higher level, they transform the way of this functioning. Psychologically, satisfying the need for novelty and development is always based on a special form of intuition. In scientific and technical creativity, the effect of an intuitive solution is also verbalized and sometimes formalized. Following the general characteristics of the central link, materials from an experimental study of psychological models of its main components - intuition, verbalization and formalization - are presented. Then other elements of the psychological mechanism of creativity are identified and analyzed, related to the general and specific abilities of people, the qualities of a creative personality, and a wide range of conditions for the effectiveness of creative work. All these elements are identified and considered as conditions conducive to the effective operation of the central link of the psychological mechanism of creativity.

The entire system of concepts of the psychology of creativity presented in the book and its internal logic are built on this same basis.

PART I

METHODOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

CHAPTER 1

THE NATURE OF CREATIVITY

Creativity as a mechanism of development

When characterizing the state of the problem of the nature of creativity, one should first of all emphasize the understanding of creativity in the broad and narrow sense, long established in the literature.

It can be found in the article “Creativity”, included in the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, written by F. Batyushkov (the broad sense is called “direct” in it, the narrow sense - “generally accepted”): “Creativity - in the literal sense - is the creation of something new. In this meaning, this word could be applied to all processes of organic and inorganic life, for life is a series of continuous changes and everything that is renewed and everything that arises in nature is a product of creative forces. But the concept of creativity presupposes a personal beginning and the corresponding word is used primarily in relation to human activity. In this generally accepted sense, creativity is a conventional term for designating a mental act expressed in the embodiment, reproduction or combination of data from our consciousness, in a (relatively) new form, in the field of abstract thought, artistic and practical activity (T. scientific, T. poetic, musical , T. in the fine arts, T. administrator, commander, etc.” (Batyushkov, 1901).

In the early period of research, a certain amount of attention was paid to the broad meaning of creativity. However, in a later period, the view of the nature of creativity changed dramatically. The understanding of creativity, both in our country and in foreign literature, has been reduced exclusively to its narrow meaning."

In relation to this narrow meaning, modern studies of the criteria of creative activity are being conducted (especially numerous abroad (Bernstein, 1966).

1 For more details, see: Ponomarev Ya. A. Development of problems of scientific creativity in Soviet psychology. - “Problems of scientific creativity in modern psychology:”. M., 1971.

11

Most modern foreign scientists involved in issues of scientific creativity unanimously believe that a lot of work has been done in the area of creativity criteria, but the desired results have not yet been obtained. For example, the authors of many studies conducted in recent decades in the United States tend to share Gieselin's point of view, according to which the definition of the difference between creative and non-creative activities remains completely subjective.

The complexity of the structure of creativity prompts researchers to think about the need for multiple criteria. However, an empirical search for such criteria leads to insignificant results. Put forward criteria such as “popularity”, “productivity” (Smith, Taylor, Ghiselin), “the degree of reconstruction of the understanding of the universe” (Ghiselin), “the breadth of influence of the scientist’s activities on various fields of scientific knowledge” (Lachlen), “the degree of novelty of ideas, approaches, solutions” (Sprecher, Stein), “social value of scientific products” (Brogden) and many others remain unconvincing2. S. M. Bernstein (1966) rightly sees this as a consequence of a completely unsatisfactory level of development of theoretical issues in the study of creativity.

It must be especially emphasized that the question of creativity criteria is far from idle. Sometimes the wrong approach to its consideration becomes a serious obstacle to the study of creativity, shifting its subject. For example, the founders of heuristic programming, Newell, Shaw, and Simon (1965), taking advantage of the uncertainty of the criteria that distinguish a creative thought process from a non-creative one, put forward the position that the theory of creative thinking is a theory of solving cognitive problems with modern electronic computing devices. They emphasize that the validity of their claims to a theory of creative thinking depends on how broadly or narrowly the term “creative” is interpreted. “If we are to view all complex problem-solving activity as creative, then, as we will show, successful programs for mechanisms that imitate a human problem solver already exist, and a number of their characteristics are known. If we reserve the term “creative” for activities such as the discovery of special3 It should be noted that all those particular criteria that relate to the characteristics of creativity in the narrow sense (as one of the forms of human activity) and which are now varied from different perspectives by most modern researchers, have already were in general terms in the works of domestic researchers of the early period (novelty, originality, departure from the template, breaking traditions, surprise, expediency, value, etc.). This indicates the stagnation of thought in this area (for more details, see: Ponomarev #. A. Development of problems of scientific creativity" in Soviet psychology).

12

tional theory of relativity or the creation of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony, then there are currently no examples of creative mechanisms."

The authors adopt the first version for practical guidance - hence their theory of creative thinking.

Of course, such a position raises sharp objections, for example, in the spirit of the statement of L. N. Landa (1967), who showed that modern heuristic programs are only “incomplete algorithms” and emphasized that heuristic programming does not characterize creative processes. Creativity lies not in that activity, each link of which is completely regulated in advance by given rules, but in that, the preliminary regulation of which contains a certain degree of uncertainty, in activity that brings new information, presupposing self-organization.

Other objections can be raised. For example, if we agree with the approach of Newell, Shaw and Simon, we will find ourselves in a very peculiar position: our studies of creativity will not be directed towards a pre-designated object, but this object itself will be what the work done will lead to. In some situations such assumptions are probably possible. But in this case, the settings of heuristic programming are rejected and the characteristics of creativity that appear quite sharply in many empirical studies, although still poorly disclosed, are ignored. After all, one can rightfully make another decision: the class of problems whose solutions are accessible to machine modeling is not included in the class of creative ones; the latter can only include those whose solutions are fundamentally not amenable to modern machine modeling. Moreover, the impossibility of simulating solutions to such problems using modern computers can be one of the fairly clear practical criteria for true creativity.

Newell, Shaw and Simon, of course, clearly understand and foresee the possibility of such a version. But they think it can be ignored. Such confidence is supported by a calculation of the precariousness of the existing criteria that distinguish a creative thought process from a non-creative one3; it is reinforced by the conviction that it is impossible to identify satisfactory objective criteria for creativity. All this is a direct consequence of the lack of proper support for generalized, regulating methodological principles that determine preliminary orientation in private research, and, moreover, the ignorance of 3 Newell, Shaw and Simon define creative activity as a type of activity for solving special problems that are characterized by novelty, unconventionality, stability and difficulty in formulating the problem (“Psychology of Thinking.” Collection of translations from German and English. Edited by A. M. Matyushkin. M., 1965).

13

riya into the possibility of productive development of such regulative principles.

Apparently, for the same reason, numerous attempts by modern foreign scientists to determine the essence of creativity are not very successful.

These attempts are clearly presented, for example, in the book by A. Matejko (1970), the author of which widely relies on the opinions of a large number of foreign researchers (especially American) and provides the most typical definitions. All of them are purely empirical and have little content. Creativity is traditionally associated with novelty, and the concept of novelty is not disclosed. It is characterized as the antipode of patterned, stereotypical activity, etc.

“The essence of the creative process,” writes Matejko, “lies in the reorganization of existing experience and the formation of new combinations on its basis.” Let's take this definition as an example.

It is easy to see that the reorganization of experience in this case is understood not as a process, but as a product. The essence of the creative process is that it leads to such a reorganization. However, the main disadvantage of this definition is not that it replaces the process with a product or loses sight of some details, but that by its very nature it is purely empirical - non-fundamental. No matter how much we try to give it a tolerable form with all kinds of improvements at the level of knowledge on which it is built, we still won’t succeed.

In this sense, a much more thoughtful definition coming from S. L. Rubinstein4 and most widespread in our domestic literature is also unacceptable: “Creativity is a human activity that creates new material and spiritual values that have social significance” b.

Given a certain selection of creative events, such a criterion is clearly unsuitable. After all, they talk about how animals solve problems, about children’s creativity; creativity undoubtedly manifests itself when a person of any level of development independently solves all kinds of “puzzles”. But all these acts do not have direct social significance. The history of science and technology records many facts when the brilliant achievements of people's creative thought did not acquire social significance for a long time. One cannot think that during the period

* According to Rubinstein, creativity is an activity “creating something new, original, which, moreover, is included not only in the history of the development of the creator himself, but also in the history of the development of science, art, etc.> (Rubinstein S.L. Fundamentals of General Psychology. M ., 1940, p. 482).

* TSB, ed. 2nd, t, 42, p. 54.

M

silencing, the activities of their creators were not generally creative, but became so only from the moment of recognition.

At the same time, the criterion of social significance in a number of cases is indeed decisive in creative acts. It cannot simply be discarded. For example, in unrecognized inventions and discoveries, on the one hand, the act of creativity is evident, but on the other, it is not. Consequently, in addition to psychological reasons in social relationships, there are some additional reasons that determine the possibility of a creative act in this area.

It is necessary, apparently, to believe that there are different spheres of creativity. Creativity in one area is sometimes just an opportunity for creativity in another area.

The same idea, but in connection with the approval of an integrated approach to the study of creativity, in particular scientific discovery, was expressed by B. M. Kedrov (1969), according to whose views the theory of scientific discovery faces a complex of problems. Their solutions should be sought by methods and means of the appropriate complex of sciences. Firstly, a historical and socio-economic analysis of the practice, the “social order” of discovery, is necessary. Secondly, a historical and logical analysis is needed that identifies the specific needs of science that stimulate this or that discovery. All this corresponds to the phylogenetic section of the development of science. An ontogenetic perspective is also necessary, revealing the scope of scientific activity and scientific creativity of the author of the discovery. Here, according to B. M. Kedrov, psychological analysis comes to the fore. The identification and development of the described set of problems creates the necessary ground for a fruitful study of the internal mechanism of the relationship between the phylo- and ontogenesis of science.

Therefore, it is necessary to question the legitimacy of the direct search for a universal criterion of creativity in the field of science: first a set of criteria must be developed that correspond to different spheres of creativity (social, mental, etc.). The success of developing each of these special criteria is directly dependent on the degree of understanding of the question of the essence of creativity, taken in the most general form - in the form of a generalization of all its manifestations at the levels of different spheres. Reducing creativity to one of the forms of human mental activity prevents the depth of such a generalization. It snatches creativity from the general process of development of the world, makes the origins and prerequisites of human creativity incomprehensible, closes the possibility of analyzing the genesis of the act of creativity, and thereby prevents the identification of its main characteristics, the discovery of various forms, and the identification of general and specific mechanisms.

At the same time, creativity is an extremely diverse concept. Even its everyday meaning, its everyday use

15

is not limited to the specific meaning in which it reflects individual events from a person’s life. In poetic speech, Ryroda is often called a tireless creator. Is this an echo of anthropomorphism, just a metaphor, a poetic analogy? Or do what occurs in nature and what is created by man really have something essentially in common?

Apparently, the understanding of creativity in a broad sense, characteristic of the early period of research, is not without content. If we leave aside the Machian formulations of some ideas characteristic of the early works of the Potebnists, we will see that their understanding of the nature of creativity is associated with the involvement of broad ideas about the laws governing the Universe, ideas about the general evolution of nature, etc. Such ideas are clearly expressed by B . A. Lezin (1907). P. K. Engelmeyer (1910) sees in human creativity one of the phases in the development of life. This phase continues the creativity of nature: both one and the other constitute one series, not interrupted anywhere and never: “Creativity is life, and life is creativity.” If Engelmeyer limits the sphere of creativity to living nature, then his follower M. A. Bloch extends this sphere to inanimate nature. He places creativity at the basis of the evolution of the world, which, in his opinion, begins with chemical elements and ends in the soul of a genius.

Are we making a mistake by refusing to understand creativity in a broad sense? The pre-scientific, fantastic worldview of people sharply separated the causes of what occurs in nature and what is artificially created by people. The scientific worldview, conditioned by a materialistic understanding of the world, indicated the true reasons for both. These reasons are generally identical. In both cases, the results of creativity are consequences of the interaction of material realities. Do we therefore have the right to reduce creativity only to human activity? The expression “creativity of nature” is not without meaning. The creativity of nature and the creativity of man are just different spheres of creativity, undoubtedly having common genetic roots.

Apparently, therefore, it is more appropriate to base the initial definition of creativity on its broadest understanding.

In this case, it should be recognized that creativity is characteristic of both inanimate and living nature - before the emergence of man, both to man and to society. Creativity is a necessary condition for the development of matter, the formation of its new forms, along with the emergence of which the forms of creativity themselves change. Human creativity is only one of these forms.

Thus, even a brief consideration of the current state of the problem of nature and the criteria of creative activity persistently pushes to the idea that for us16

To advance this problem on foot, a decisive breakthrough from the particular to the universal and regulation of the process of further identifying the particular from the position of the universal are necessary.

Here we will pay attention to only one of the possible approaches to such a breakthrough - to the hypothesis formulated by us in a number of works (Ponomarev, 1969, 1970), according to which creativity in the broadest sense acts as a mechanism of development, as an interaction leading to development.

The idea of the creative function of interaction was clearly expressed by F. Engels in “Dialectics of Nature”: “Interaction is the first thing that appears to us when we consider moving matter as a whole from the point of view of modern natural science”6.

In interaction, Engels saw the basis of the universal connection and interdependence of phenomena, the final cause of movement and development: “All nature accessible to us forms a certain system, a certain collective connection of bodies, and here we understand by the word body all material realities, starting from a star and ending with an atom and even a particle of ether, since the reality of the latter is recognized. The fact that these bodies are in mutual connection already implies that they influence each other, and this mutual influence on each other is precisely movement.”7

Further, F. Engels writes: “We observe a number of forms of movement: mechanical movement, heat, light, electricity, magnetism, chemical combination and decomposition, transitions of states of aggregation, organic life, which all - if we exclude organic life for now - transform into each other. .. are a cause here, an effect there, and the total sum of motion, with all changes in form, remains the same (Spinoz’s: substance is causa sui (the cause of itself. Ed.) - perfectly expresses interaction). Mechanical motion turns into heat, electricity, magnetism, light, etc., and vice versa (on the contrary. Ed.). Thus, natural science confirms what Hegel said... - that interaction is the true causa finais (ultimate cause. Ed.) of things. We cannot go further than the knowledge of this interaction precisely because there is nothing more to know behind us. Once we have cognized the forms of motion of matter (for which, however, we still lack a lot due to the short-lived existence of natural science), then we have cognized matter itself, and this exhausts knowledge.”8

This hypothesis implies a refusal to reduce the concept of “creativity” to its narrow meaning - to human activity,

8 Marx K. and Engels F. Soch., vol. 20, p. 546.

7 Ibid., p. 392.

8 Ibid., p. 546.

17

More precisely - to one of the forms of such activity, and a return to the broad meaning of this concept.

A broad understanding of creativity, considering it in general terms as a mechanism of development, as an interaction leading to development, is very promising. Such consideration includes the question of the nature of creativity in an already fairly explored area of knowledge and thereby facilitates subsequent orientation in its particular forms. The analysis of creativity is included in the analysis of developmental phenomena. Creativity as a mechanism of development acts as an attribute of matter, its integral property. The dialectic of creativity is included in the dialectic of development, which has been fairly well studied by Marxist philosophy9. The universal criterion of creativity acts as a criterion of development. Human creativity thus acts as one of the specific forms of manifestation of the development mechanism.

Development and interaction

Thus, creativity - in the broadest sense - is an interaction leading to development. Studying any particular form of creativity, we also encounter its general laws. However, the general nature of creativity is still clearly insufficiently analyzed, although the need for such an analysis is becoming increasingly acute, especially with modern attempts to coordinate various aspects of the study of human creative activity. Attempts to carry out such coordination, guided only by “common sense”, do not achieve the goal - this is evidenced by practice. It is necessary to develop initial principles for the study of creativity.

In this direction, the scheme of the relationship between interaction and development, presented by us in a number of works (Ponomarev, 1959, 1960, 1967, 1967a), is of particular interest. This scheme was developed, reused, refined and enriched during the implementation of the principles of dialectical materialism in experimental studies of psychology

In this work we do not consider the problem of development itself in its general form. Let us only note that in order to reveal the content of the hypothesis we have put forward, along with the philosophical analysis of development, all areas of knowledge in which the genetic approach is used are of great interest. These are some aspects of the study of the microworld in physics, and the study of the evolution of matter in chemistry, and cosmogony, and geology, and the study of problems of the origin of life, biological evolution, anthropogenesis, the history of the development of society, etc. There are many reasons to assume that the richest material in this regard is contained today in historical materialism.

We will present our material, concretizing the hypothesis put forward, in subsequent sections when analyzing the psychological mechanism of creativity.

18

creative thinking and intellectual development. Let's consider its main elements and principles.

The main elements of this diagram are: system and component, process and product.

System and component. Considering the categories of whole and part, simple and composite, F. Engels emphasized their limitations, directly pointing out that such categories become insufficient in organic nature. “Neither the mechanical combination of bones, blood, cartilage, muscles, tissues, etc., nor the chemical combination of elements constitutes an animal... An organism is neither simple nor composite, no matter how complex it is.” An animal organism cannot have parts - “only a corpse has parts”10.

Apparently, the selection of a part in the sense of the word that is included in this category is associated with the destruction of the whole, that is, with the destruction of that single interacting system of components, for the analysis of which neither the categories of whole and part, nor simple and composite are sufficient. In an interacting system, one can therefore consider not one or another part of it, but one or the other side, one or another component. Moreover, the point, of course, is not in the words, not in the names, but in the meaning that is invested in these concepts. In order not to violate the integrity of the system, it is necessary to consider each side, each component in the relationships by which they are connected with other parties, other components of the system.

From here it becomes clear that it is not enough to study any isolated object. Only an interacting system can be the true subject of scientific analysis. If we do not fulfill this requirement, then, having arbitrarily snatched a component from its corresponding system of interaction and thereby turning it into an isolated “part,” we will then, one way or another, include this part in some other system of relations and thereby impose on this component qualities that are unusual for him in reality. “Interaction,” wrote F. Engels, “excludes everything absolutely primary and absolutely secondary; but at the same time it is a two-way process that, by its nature, can be viewed from two different points of view; to be understood as a whole, it even needs to be examined separately, first from one and then from another point of view, before the total result can be summed up. If we unilaterally adhere to one point of view as absolute in contrast to another, or if we arbitrarily jump from one point of view to another depending on what our reasoning at the moment requires, then

10 Marx K. and Engels F. Soch., t, 20, p. 528, 529,

1%

we remain captive to the one-sidedness of metaphysical thinking; The connection of the whole eludes us, and we become entangled in one contradiction after another.”11

Process and product. Giving the most general description of labor, K. Marx writes: “Labor is, first of all, a process taking place between man and nature, a process in which man, through his own activity, mediates, regulates and controls the exchange of substances between himself and nature. ...In the process of labor, human activity with the help of a means of labor causes a predetermined change in the subject of labor. The process fades into the product. The product of the labor process is use value, the substance of nature adapted to human needs through changes in form. Labor connected with the subject of labor. Labor is embodied in an object, and the object is processed. ...The same use value, being a product of one labor, serves as a means of production for another labor. Therefore, products represent not only the result, but at the same time the condition of the labor process” 12.

Analyzing any interacting system in a functional sense and abstracting from its specific features, we thus identify two more general categories of our scheme - product and process. The first reflects the static, simultaneous, spatial side of the system. The second reveals a different side of her; a process is a dynamic, successive, temporary characteristic of interaction.

This scheme implements the following principles.

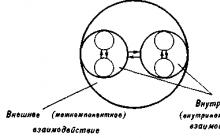

The concept of a system and its components is relative. Their identification is always abstract, since any reality is a system only in relation to its constituent components. At the same time, any reality considered as a system is always part of another, more complexly organized system, in relation to which it itself is a component (Fig. ,a).

Thus, in each specific case we can only talk about the system selected for analysis, taking into account that it itself is a component (pole) of a more complexly organized system. The reverse course of consideration is equally applicable - the decomposition of the original system into forming poles, which themselves constitute complexly organized systems (Fig. 1.6).

This is the static structure of interacting systems.

11 Marx K. and Engels F. Soch., vol. 20, p. 483-484.

12 Marx K. n Engels F. Soch., vol. 23, p. 188, 191-192.

20

Organizing systems of interaction (communication) have approximately the same structure, i.e. the dynamic structure of interacting systems is approximately the same. Here we can distinguish intercomponent and intracomponent interaction (Fig. 2).

Intercomponent (external with respect to these poles) connection involves reorganization (change of shape) of the structures of components through special internal (relative to

Rice. 1

data components) connections. These second type of interactions are qualitatively different in form from the first, which gives the right to specially highlight them.

The concepts of external and internal interactions are relative; they are determined by the choice of the initial system. Internal connections become external when we, abstracting from the system in which the component is included, consider it as an independent system. It follows that the definition

Fig.2

The concepts of “external” and “internal” are acceptable only within the framework of the system selected for analysis, without going beyond its boundaries.

The functioning of the interacting system is carried out through transitions of process into product and vice versa - product into process (the detail of such transitions is inexhaustible). What on the process side appears dynamically and can be recorded in time, on the product side is found in the form of a property at rest. Products of interaction21

events, arising as a consequence of a process, turn into the conditions of a new process, thus exerting a reverse influence on the further course of interaction and at the same time becoming, in a number of cases, stages of development 13.

Depending on the properties inherent in the components (formed as products of corresponding processes) and the conditions for their manifestation during a given interaction, a method of interaction is formed (which in turn serves as the basis for classifying a given system as one form or another).

Noting that the method of communication is determined by the properties of the components, it is also necessary to point out the inverse dependence of these properties on the method. Previously, we said that each of the components, being a side of the analyzed system, itself represents some interacting system that has its own internal structure. This latter determines the properties that the component discovers when interacting with an adjacent component. However, given that the internal structure of the component itself is formed in the course of external, intercomponent interaction, it should be considered that the method of communication has the opposite effect on the formation of its defining properties. Cause and effect here dialectically change places.

Let's consider this situation in a little more detail. It is known that the condition for any interaction process is a certain imbalance in the system of components that has developed at a certain moment. This imbalance can be caused not only by influences external to a given system, as well as by influences external to any individual component, but also by those phenomena that occur within the component itself (in the final case, a “split of the one”, for example, in nonliving conditions, interaction and development constitute an inextricable unity: development in all cases is mediated by interaction, since the product of development is always a product of interaction;

interaction itself is closely dependent on development; if development cannot be understood without knowing the laws of interaction, then interaction outside of development remains incomprehensible, since the specific forms of manifestation of the laws of interaction are directly dependent on at what stage of development we trace them, since these stages of development become conditions of interaction.

Emphasizing the real unity of interaction and development, we are together

At the same time, we affirm that both have certain specificity and qualitatively unique laws, the study of which requires mental dissection. Abstracting from development data, it is first necessary to trace the features of interaction; based on these research data

USSR ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

INSTITUTE OF PSYCHOLOGY

Y. A. PONOMAREV

PSYCHOLOGY OF CREATIVITY

PUBLISHING HOUSE "SCIENCE> MOSCOW 1976

The book examines the subject and methods of the psychology of creativity, the central link in the psychological mechanism of creative activity, the abilities and qualities of a creative personality. It contains extensive experimental material, on the basis of which a number of psychological laws of creative activity and laws of the formation of conditions favorable to it are formulated.

The book is addressed to psychologists, philosophers and a wide range of readers interested in problems of creativity.

n 10508-069 „. ?6 042 (02)-76

© Nauka Publishing House, 1976

INTRODUCTION

RESEARCH OF CREATIVITY IN CONDITIONS OF SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL REVOLUTION

The psychology of creativity - a field of knowledge that studies the creation of new, original things by a person in various fields of activity, primarily in science, technology, and art - came up in the middle of the 20th century. to a new stage of its development. Particularly dramatic changes have occurred in the psychology of scientific creativity: its authority has increased, its content has become deeper. It has taken a dominant place in creativity research.

The conditions for a new stage in the development of the psychology of scientific creativity arose in the situation of the scientific and technological revolution, which significantly changed the type of social stimulation of activity research in science.

For a long time, society did not have an acute practical need for the psychology of creativity, including scientific creativity. Talented scientists appeared as if by themselves; they spontaneously made discoveries, satisfying the pace of development of society, in particular science itself. The main social incentive for improving the psychology of creativity remained curiosity, which sometimes mistook a little controlled invention, a game of fantasy, for a perfect product of scientific research.

The lightness of the criteria for assessing the quality of research in the psychology of creativity was also imposed by its historical traditions. Most of the pioneers of creativity research were idealistic thinkers. They saw in creativity the most fully expressed freedom of manifestation of the human spirit, not amenable to scientific analysis. The idea of purposefully increasing the efficiency of creating new, original, socially significant values was considered as empty fun. The existence of objective laws of human creativity was actually denied. The main task of creativity researchers was to describe the circumstances surrounding creative activity. Legends were collected that sparked the curiosity of gullible readers. Even the most kind

All these studies have been collected over the centuries under the common banner of “creativity theory.” Since the last decades of the 19th century. they began to be referred to as the “psychology of creativity.” Psychology was then understood as the science of the soul, of ideal spiritual activity.

A rough idea of the nature of the “theory and psychology of creativity” at the beginning of the 20th century. can be made, for example, based on the materials of value judgments relating to this area of knowledge and given in the works themselves on the “theory and psychology of creativity”, in other words, based on the impression of observers who consider their science from within itself.

Some authors of that time did not dare to classify the theory of creativity and the psychology embedded in it as a scientific discipline. From their point of view, it is rather a tendentious grouping of fragmentary facts and random empirical generalizations, snatched without any method, without any system or connection from the fields of physiology of the nervous system, neuropathology, history of literature and art. These fragmentary facts and random empirical data are accompanied by a number of risky comparisons and hasty generalizations of data from aesthetics and literature, and at the same time a number of more or less subtle observations, introspections, supported by references to the autobiographical self-confession of poets, artists, and thinkers.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, after research into artistic and scientific-philosophical creativity, research into natural science creativity appeared, and somewhat later, into technical creativity. They delineated the subject of research more strictly. This had a beneficial effect on the productivity of creativity learning. Some circumstances common to all types of creativity have emerged. Attention began to focus on more significant phenomena.

However, the principles of creativity research have largely changed little. This happened not only because the subject of research was indeed very complex, but mainly because until the middle of our century, the study of creativity was not given significant importance.

In the middle of the 20th century. curiosity, which stimulated the development of knowledge about creativity, lost its monopoly. A clearly expressed need for rational management of creative activity has arisen - the type of social order has changed dramatically.

Emphasizing this sharp change in the type of social order, let us draw attention to the following circumstance: the new need of society was not generated by the internal development of the psychology of creativity - it was not this area of knowledge that indicated to society

possibility and feasibility of creativity management. The shift in social stimulation was caused by the scientific and technological revolution - a qualitative leap in the development of productive forces, which turned science into a direct productive force, making the economy significantly dependent on the achievements of science.

In recent years, our scientific literature has shown conditions conducive to the intensification of research into the psychology of creativity. The complexity of the problems that science has approached to solve, the ever-increasing provision of scientific research with the latest technical means are closely related to changes in the structure of the organization of this research, the emergence of new organizational units - scientific teams, the transformation of scientific work into a mass profession, etc. The age of handicraft in science is gone to the past. Science has become a complexly organized system that requires special research to consciously manage the course of scientific progress.

Research on creativity is of particular importance. Life presents researchers in this area with a complex of practical problems. These tasks are generated by the fact that the pace of development of science cannot be constantly increased only by increasing the number of people involved in it. We must constantly increase the creative potential of scientists. To do this, it is necessary to purposefully form creative scientists, carry out rational selection of personnel, create the most favorable motivation for creative activity, find means that stimulate the successful course of the creative act, rationally use modern possibilities for automating mental work, approach the optimal organization of creative teams, etc.

The old type of knowledge, stimulated by curiosity - mainly the contemplative-explanatory type - could not, of course, satisfy the new need of society, cope with the new social order - to ensure rational management of creativity. There had to be a change in the type of knowledge, a new type had to emerge—effectively transformative. Has such a change occurred?

Let us take a look from this point of view at the modern psychology of scientific creativity in the USA, where research in this area is currently most intensive.

In 1950, one of the leading psychologists in the US-D. Guilford appealed to his colleagues in the association to expand research on the psychology of creativity in every possible way. The call met with a corresponding response. Many publications have appeared under the heading of the psychology of creativity. They covered, it would seem, all the traditional problems of this field of knowledge: questions of criteria for creative activity and its difference from non-creative activity, the nature of creativity, patterns

the creative process, the specific characteristics of a creative personality, the development of creative abilities, the organization and stimulation of creative activity, the formation of creative teams, etc. However, as it became clear, the scientific value of this stream of publications is small. And first of all, because the acceleration of this kind of research by US scientists occurred despite the obvious unpreparedness of the theory.

Modern psychology of scientific creativity in the United States is narrowly utilitarian. At the cost of expensive, unproductive efforts, she tries to obtain direct answers to the practical problems put forward by life. Sometimes US psychologists, relying on “common sense”, vast empirical material and its processing using modern mathematics, manage to offer solutions to certain practical problems. However, such successes are palliative. It is important to note that the vast majority of such tasks are not strictly psychological. Rather, these are “common sense” tasks. Their solutions are of a narrowly applied nature and are confined to purely specific situations. The mechanisms of the phenomena being studied are not revealed, and therefore their invariants are not revealed. Some modifications of specific conditions make previously obtained solutions no longer suitable and require new empirical research.

Excessive enthusiasm for superficial analysis is fraught with obvious danger, especially when it is associated with an appeal to social objects, the external appearance of which is easily accessible to direct observation, while their internal structure is diverse and extremely complex. Superficial work at first often achieves a certain success, successfully using some of the previously accumulated valuable knowledge. This creates a certain authority for the emerging direction. It becomes recognized and popular. Then follows an idle move, which already interferes with the development of full-fledged research, veiling its true problems and real difficulties, creating the appearance of satisfying practical needs.

An analysis of the psychology of scientific creativity in the United States shows that the scientific and technological revolution took creativity research by surprise. There was no accumulated knowledge that could be called fundamental. The ideas contained in these studies were already put forward in general terms before the 40s of our century.

There is no reason to think that the ideas and principles already known by this time correspond to the new social incentive; we do not have sufficiently convincing facts about the rational management of scientific creativity.

Therefore, as the most important characteristic of the modern situation in the field of research into problems of creativity, we must name the contradiction consisting in the inconsistency of what has been achieved

the level of knowledge and the social need for it, i.e., in the discrepancy between the type of social order and the type of knowledge achieved - in the lag between the type of knowledge and the type of order.

Of great importance for finding ways to overcome this contradiction is the analysis of trends in the historical development of the psychology of creativity. A general idea of the genesis of the ideas of modern creativity psychology can be successfully built on the material of domestic science. The author of “The History of Soviet Psychology” A.V. Petrovsky (1967), characterizing Russian psychology at the beginning of the 20th century, emphasizes that it “represented one of the detachments of European psychological science. The research of domestic scientists devoted to individual psychological problems cannot be considered in isolation from the corresponding works of their foreign colleagues, whose ideas they developed or refuted, whose influence they experienced or which they themselves influenced.” Everything said here fully applies to the psychology of creativity. Therefore, consideration of its problems in Russian science reveals to us not only the own positions of domestic authors, but also makes it possible to get an idea of the state of the psychology of creativity of that time abroad. In general, the same can be applied to Soviet psychological science. At the same time, after the victory of the Great October Socialist Revolution, deep fundamental changes occurred in the development of psychological thought in the USSR: a gradual rethinking of psychological research began on the basis of dialectical-materialist methodology, which gave an extremely valuable and essential originality to our research and freed many scientists from idealistic wanderings.

The genesis of the ideas of the psychology of creativity, the features of the general approach to research, the dynamics of transformations of this approach and the trend of its strategic direction were traced by the author in the work “Development of problems of scientific creativity in Soviet psychology” (1971), which also included the pre-October period. It examines the works of the pioneers of the emerging study of the psychology of creativity in Russia - followers of the philosophical and linguistic concept of A. A. Potebnya - D. N. Ovsyaniko-Kulikovsky (1902, etc.) and his student B. A. Lezin (compiler and editor of the collections “Questions theory and psychology of creativity", the main tribune of Potebni-stov), works by P. K. Engelmeyer, M. A. Bloch, I. I. Lapshin, S. O. Gruzenberg, V. M. Bekhterev, V. V. Savich, F. Yu. Levinson-Lessing, V. L. Omelyansky, I. N. Dyakov, N. V. Petrovsky and P. A. Rudik, A. P. Nechaev, P. M. Yakobson,

V. P. Polonsky, S. L. Rubinshtein, B. M. Teplov, A. N. Leontyev, I. S. Sumbaeva, B. M. Kedrova, Ya. A. Ponomarev,

S. M. Vasileisky, G. S. Altshuller, V. N. Pushkin,

M. S. Bernshtein, O. K. Tikhomirov, M. G. Yaroshevsky, V. P. Zinchenko and others.

The results of our earlier analysis of the development of problems of scientific creativity in Soviet psychology are used by us in many sections of this book. Here we will only point out the main trend of changes in the general approach to creativity research.

This tendency is expressed in a gradual movement from an undifferentiated, syncretic description of the phenomena of creativity, from attempts to directly embrace these phenomena in all their concrete integrity to the development of an idea of the study of creativity as a complex problem - in movement along the line of differentiation of aspects, identifying a number of different the nature of the laws that determine creativity.

Let us also note that today such differentiation is still far from complete.

Our domestic scientists have made a very important contribution to the study of the psychology of creativity. Great and varied interest in this area of knowledge is characteristic of the first days after October. It survived until the mid-30s, but then declined and almost disappeared. Currently, the curve of this interest has risen sharply again.

Despite some pause in the study of the psychology of creativity, we have significant advantages over bourgeois scientists: our psychological research, based on the most progressive Marxist-Leninist methodology in the world, has brought us significantly closer to turning the psychology of creativity into effectively transformative knowledge. In contrast to “psychological and sociological” studies of increasing the efficiency of creative work in science, conducted at the level of “common sense,” we pay main attention to the analysis of the theoretical foundation of the psychology of creativity, identifying and overcoming theoretical difficulties.

It is customary to begin the presentation of any field of knowledge with a description of its subject. But we do not have such an opportunity.