Introduction

Main part.

1. Basic ideas of D. Locke’s theory of knowledge

2. The relationship between primary and secondary qualities according to Locke

Conclusion

List of used literature

Introduction

Since the real processes of development in society of relations of knowledge and morality were reflected in the philosophical and ethical theories of their historical eras in the long and spiritually rich history of ideas, then in general, it is possible to solve this problem by turning to the history of the most significant teachings of the past, which laid the foundations of our modern views on these issues. Of particular interest is the 17th century, an important period in human history. In the modern era, the basic ideas characteristic of European consciousness were developed, which formed the general theoretical basis of historical and philosophical teachings up to the present day. There was a radical revision of views on man, which largely stimulated the development of empirical natural science in subsequent centuries. For philosophy itself, this resulted in a decisive reorientation towards empiricism and sensationalism. The actual social factors in determining the boundaries of theoretical knowledge were revealed, which opened up prospects for the development of moral philosophy.

England was the true center of innovative thought. Hence the need for special attention to the work of British empiricists of that time and, above all, John Locke. The name of John Locke (1632-1704) occupies a very honorable place not only among the great philosophical names of the modern era, but also in the world historical and philosophical process. The philosophical concepts of the theory of knowledge and morality of the English thinker served as a kind of connecting element between the philosophical and socio-ethical thought of the 17th and 18th centuries. It should be noted that Locke played an outstanding role in the development of political concepts of the 17th century, leaving to his descendants a fairly fully developed system of ideas that formed the basis of modern politics. The philosophical doctrine of education, which served to develop the philosophical and pedagogical thought of the Enlightenment, also goes back to Locke. It seems quite obvious that for Locke himself, epistemological and political-legal issues were in the first place of his philosophical interests, and not the study of issues of human moral behavior and the creation of a science of morality. This is confirmed by the very title of the philosopher’s main work, “An Essay on Human Understanding.”

Russian historical and philosophical science has made a significant contribution to the study of the philosophical heritage of the great English thinker. Pre-revolutionary literature about Locke is represented by the works of such authors as A. Vishnyakov, V. Ermilov, E. F. Litvinova, V. N. Malinin, V. S. Serebrenikov, N. Speransky, V. V. Uspensky. Among the post-revolutionary researchers, K.V. Grebenev and D. Rakhman stand out, first of all. A number of dissertation studies are devoted to the analysis of Locke's theory of knowledge.

The colossal influence of Locke's ideas, and in particular the theory of knowledge, on the formation of philosophical thought of the New Age is recognized by modern domestic researchers. The results of I. I. Borisov’s research on the abilities and boundaries of human knowledge in Locke’s teaching turned out to be fruitful for our analysis.

The purpose of the abstract: to highlight and analyze the main ideas of Locke's theory of knowledge.

Main part

1. D. Locke's theory of knowledge

D. Locke's main work on theoretical philosophy, “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding,” was completed in 1687 and published in 1690.

The years before the Revolution of 1688, when Locke could not take any theoretical or practical part in English politics without serious risk, he spent writing his Essay Concerning Human Understanding. This is his most important book, the one that brought him most fame, but his influence on the philosophy of politics was so great and so lasting that he can be considered the founder of philosophical liberalism, as well as empiricism in the theory of knowledge.

Locke is the most successful of all philosophers. He completed his work on theoretical philosophy just at the moment when the government of his country fell into the hands of people who shared his political views. In subsequent years, the most energetic and influential politicians and philosophers supported both in practice and theory the views that he preached. His political theories, developed by Montesquieu, are reflected in the American Constitution and find application wherever there is a dispute between the President and Congress. The British Constitution was based on his theory some fifty years ago, and so was the French Constitution adopted in 1871.

In 18th-century France, Locke initially owed his influence to Voltaire. Philosophers and moderate reformers followed him; the extreme revolutionaries followed Rousseau. His French followers, right or wrong, believed in a close connection between Locke's theory of knowledge and his views on politics.

In England this connection is less noticeable. Of the two most famous followers of Locke, Berkeley was not a significant figure in politics, and Hume belonged to the Tory party and outlined his reactionary views in the History of England. But after Kant, when German idealism began to influence English thought, a connection between philosophy and politics arose again: the philosophers who followed the German idealists were generally conservatives, while the followers of Bentham, who was a radical, remained faithful to the Lockean tradition. However, this ratio was not constant; T.G. Greene, for example, was both a liberal and an idealist.

Not only Locke's correct views, but even his mistakes in practice were useful.

The experiential component of knowledge, inherent in principle to both empiricists and rationalists, was developed with the greatest consistency in the century under review by Locke. The author of “An Essay on Human Understanding” argued that “all our knowledge is based on experience, and from it, in the end, it comes” (57: 1, 154). Experience consists of two sources: sensations and reflection.

Locke understood external experience as consisting of sensations, and internal experience as formed by the soul’s sensory reflection (reflection) of its own activity.

Thus, Locke understood experience as the totality of external and internal sensations, stating that in this sense “all ideas come from sensation and reflection” (57: 1, 154). The philosopher consistently pursued the principle of sensationalism, formulated in ancient philosophy - “there is nothing in the mind that was not previously in the feelings.”

Locke's philosophy, as can be seen from the study of the Essay Concerning Human Understanding, is all permeated with certain advantages and certain disadvantages. Both are equally useful: the disadvantages are such only from a theoretical point of view.

Locke is always prudent and would always rather sacrifice logic than become paradoxical. He proclaims general principles, which, as the reader can easily imagine, are capable of leading to strange consequences; but whenever such strange consequences seem ready to appear, Locke tactfully refrains from drawing them out. Since the world is what it is, it is clear that correct inference from true premises cannot lead to errors; but premises can be as close to the truth as is theoretically required, and yet they can lead to practically absurd consequences.

A characteristic feature of Locke, which extends to the entire liberal movement, is the absence of dogmatism. The belief in our own existence, the existence of God, and the truth of mathematics are the few certainties that Locke inherited from his predecessors. But no matter how different his theory is from the theories of his predecessors, in it he comes to the conclusion that truth is difficult to possess and that a reasonable person will adhere to his views, retaining a certain amount of doubt.

An important procedure that was carried out by Locke is related to the classification of the activities of the mind. After we have received ideas from experience, we must process them. This processing can be carried out in only three ways. We can either separate ideas obtained from experience - separate them from each other - in which case we are dealing with the operation of abstraction; Moreover, Locke does not see the limits of the separation of ideas: it seems to him that any idea can be separated from any other; then they objected to him (in general, his theory of abstraction was sharply criticized). We can connect ideas; in particular - in judgment this happens. And we can compare ideas.

Locke also applied his classificatory efforts to the problem of types of knowledge.

First, he implicitly distinguishes between existential propositions and essential ones - those concerning the existence of a thing and its essence. And here three types of knowledge are possible: intuitive, demonstrative and sensual. Or intuitive knowledge, demonstrative knowledge and faith (because sensory knowledge comes close to faith).

Locke understands intuitive knowledge in the same way as Descartes. What he calls demonstrative knowledge corresponds to Descartes' deductive knowledge - just another term for the same thing (Locke's demonstration is the same as Descartes' deduction). And sensory knowledge also has analogues in Descartes’ philosophy: when he, for example, talks about the conviction in the existence of the external world - this is what Locke means here by sensory knowledge. The most perfect, of course, is intuitive knowledge, then demonstrative, and the least reliable is sensory knowledge.

He discusses all these problems in the fourth part of “Experience...”. It has the most ontological character, because here Locke applies all these reflections to a discussion of the problem with which Descartes began his philosophy. But Locke, on the contrary, discusses this towards the end, namely, the degree of reliability of our knowledge about the existence of the soul, the world and God.

Another popular misconception about Locke is that he is a materialist philosopher. There are always some grounds for this kind of judgment; they do not arise out of nowhere. For Locke, the existence of God is more certain than the existence of the external world. The external world is sensual. This is not what is given. This is not the external world - what we are now realizing - these are all ideas, according to Locke. What we see, we are directly aware of - we remain within the framework of our own subjectivity.

We cannot directly perceive any material thing: we perceive only our own ideas. Ideas are caused by things to whose existence we must infer. Because in principle it can be a dream - everything we see - or it can be directly caused by God. That is, here, from the fact that we see this world, it does not follow that it exists independently of us, firstly; and, secondly, that it is caused by similar things - to those things that we see. At least there are no flowers (in real things) and so on. But one can generally pose the question: does this world exist? how do we know that he is behind our ideas?

Descartes proved the existence of the material world, starting from the idea of the truthfulness of God. But for Locke this is too metaphysical an argument, so it does not prove the existence of the external world at all. Locke is much more skeptical than Descartes in this regard. In general, he takes a skeptical position on a number of issues - both about the bearer, for example, of the psyche (its substantiality or non-substantiality) - and here: the existence of the external world is unprovable. We know the existence of our own soul from intuition - it is intuitively obvious, reliable. The existence of God can be strictly proven, Locke claims. Strictly. Because demonstration is the highest degree of evidence. But here we can't do anything.

True, he reassures us that, firstly, the belief in the existence of the external world is already very strong, so there is no need for special evidence. But in reality, he continues, nothing changes. It would seem a paradoxical reasoning.

Locke's main goal is to determine the sources of ideas and types of knowledge, the types of reliability arising from the comparison, connection or separation of these ideas. By idea Locke means any object of thought. He understands thinking absolutely in the Cartesian sense, as consciousness about something.

An idea is any object of thought, and thinking is any mental act accompanied by consciousness.

Consciousness can work with non-concepts. So you feel, you realize that you are now seeing something in front of you - it doesn’t even matter what; Now you realize this spot - this is an act of thinking, realized in the form of sensation, in this case. Thinking has nothing to do with concepts. Thinking is any act of consciousness, and consciousness is not necessarily conceptualized. Only the activity of intellect or reason is relevant to concepts.

Just like Descartes, Locke denies unconscious perceptions - since he connects consciousness with thinking; unconscious ideas, to be more precise. There is none of this. The soul is completely permeated with consciousness. Locke immediately speaks - here, in the “Introduction” - about the negative and positive tasks of his treatise.

This means, negative or restrictive, the result of all his research will be the understanding that not all questions - traditional questions of metaphysics - are within the power of the human mind. Why do we even... - well, we need to understand this clearly - why take on the study of the soul, the study of the abilities of the soul? What's the point of this? You can, of course, answer this question that it is valuable in itself - this is really so, there is no need to look for any other benefit; It's just important in itself. But there are also external benefits.

After we find out how our cognition works, we will automatically draw certain limits around it, beyond which our abilities are not able to penetrate - this is the so-called limiting task.

This problem can be solved only as a result of a strict and thorough analysis of mental forces. This is the positive side. That is, both the positive part - the actual analysis of the structure of the soul - and the restrictive conclusions that follow from this; Locke clearly articulates these two sides of the issue. And then it was duplicated many times, this is the structure, in the works of modern European authors: in Hume, for example.

The most famous example is Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason” - it is at the same time a study of the transcendental abilities of knowledge, i.e. a positive action, and a limitation of cognizable objects. And the word “criticism” includes two meanings, and in the “Critique of Pure Reason” these two meanings are indeed very successfully combined. Criticism is also a kind of disagreement, denial; and criticism is research, if we talk about the etymology of a word.

Let's return to Locke. After he completes the artillery preparation, he begins to figure out the question, where do ideas come from? He has two options: either they are a priori, that is, already given in advance in the soul, or from experience. There are no other options. Pre-experimental ideas are called innate. Locke proves that there are none. How he does it? He uses a very simple and effective argument. He asks the question: “Tell me, these are innate ideas - let’s say they exist. But what does “innate idea” mean? This means that it is inherent in human nature; not to any specific person, no matter where this person lives, in what conditions, etc. – if the idea is innate, it will always be present in him. So? This means that if a person has innate ideas, then all people must have them; since, if they are inherent in human nature, then, accordingly, they must be inherent in all people who are people precisely because they have human nature. So, if innateness is associated with the universality of ideas - if they are universal, then they should be immediately understandable to everyone.

Locke talks about inner feeling as one of the sources of ideas - about inner experience. But what does this experience reveal to us? He reveals to us the structure of his own soul and its abilities. This means that it is already assumed, by the very figure of speech, that there is a soul that has certain abilities that are inherent in it regardless of external objects. And we can call these abilities innate. Abilities can be called innate. Which is what Locke does.

He acknowledges innate abilities - this time directly. The innate abilities of the soul are those laws according to which the activity of the soul is carried out and which are found, belong to its nature, and are not taken from somewhere outside. These laws can be discovered in the inner feeling. These laws, or forms of activity, correspond exactly to what Descartes would call “innate ideas of class II,” such as thinking, consciousness, etc. That is, in this regard, the difference between Descartes and Locke is small.

So, if there is no innate knowledge in such an absolute sense, but one can only speak in a conditional way, then all our knowledge is taken from experience. Experience can be, as I already said, external and internal. Ideas of external experience, or external sense, Locke calls ideas of sensations. He calls ideas that are supplied to us by inner feeling ideas of reflection. Again, the term “idea” is used widely by him. He calls an idea what you now directly feel in front of you - notebooks, pens - these are ideas according to Locke, and not the things themselves. He adheres to the same concept of a duplicated world as Descartes. The idea of sensation, he continues, arises in the soul as a result of the influence of external objects on us.

There is a soul. Objects affect the soul. When influencing the soul, external things seem to trigger its internal mechanisms. It turns on - the soul, after external influence, and begins to do something with the ideas received: firstly, it remembers them, these ideas, then reproduces, compares, separates, connects. Now these are spiritual actions. And these mental acts are revealed in reflection.

A simple idea (the definition is quite difficult, like any elementary concept) is an object of thought in which we in no way can detect an internal structure, a part. For example, the idea of color: red is a clear example of a simple idea. Or let’s take some taste, smell: no parts can be found in the smell - this is a simple idea. Simple ideas can be combined; conglomerates arise, which Locke calls complex ideas. An example of a complex idea is a lump of snow. This image combines whiteness, coldness, friability and many other qualities, each of which is a simple idea.

Simple ideas must be distinguished from modes of simple ideas - a rather complex concept in Lockean philosophy. Modes of simple ideas arise through repetition, through the multiplication of the same qualitative certainty. An example is extension. If we ask: is the idea of extension a simple or a complex idea, then we find ourselves in a somewhat ambiguous position, according to Locke. On the one hand, extension is thought of as something homogeneous. That said, it's a simple idea. But on the other hand, extension is divisible. And divisibility is the quality of a complex idea. Locke combines this ambivalence in the term "mode of the simple idea." A simple idea of extension will be a certain idea of an elementary extension, the atomicity of some kind, or something, of some point. But, one way or another, there is reproduction of the homogeneous here. Which is fixed by the corresponding term.

Locke formulates a general law: all ideas, he says, arise from experience. Not all ideas in general, but all simple ideas are taken from experience. Whereas complex ideas may not have archetypes in experience. Imagine a platinum mountain, for example. That's the idea. Have you seen the platinum mountain? Of course not. So not all ideas come from experience? What is this innate idea - a platinum mountain? No, it's just a complicated idea. But the idea of platinum and the idea of a mountain, which can conditionally be called simple ideas (they are actually not simple, they can be further divided - that’s not the point) - they have an experienced archetype. That is, there was something in the sensations that corresponded to them.

As for the idea of sensation, there are many types of them, and most of the total mass of sensations is divided according to the divisions of the sense organs. Here, a person has five senses - accordingly, five enormous classes of ideas of sensations: visual, tactile, olfactory, gustatory, tactile and auditory. These are simple; If we talk about the elementary components of each of these classes, then yes: these are simple ideas of sensations.

Some ideas, says Locke, are not only connected with sensations, but can also be connected with reflection; that is, not only with external, but also with internal feeling. Well, firstly, the idea of being, for example, or the idea of unity: they are not specified by external feeling. That is... these ideas can be obtained from both external and internal feelings. It’s the same with the ideas of pleasure and pain: pleasure can be caused by pleasant sensations of taste, or it can be caused by a feeling of one’s own freedom. Here Locke is talking, in fact, about the long-standing division of pleasures into bodily and intellectual. Well, it looks pretty standard here so far, he doesn’t make any discoveries here.

But it is more interesting to understand his position regarding simple ideas of reflection - specific, moreover, ideas. Reflection is looking out of oneself; that is, the gaze reveals the forms of activity of our soul, and accordingly the question of what simple ideas of reflection exist is equivalent to another, very important question: in what main types of activity does the soul realize its essence? In what, in other words, is the essence of the soul manifested? It is in what the essence of the soul is manifested that we will have to call simple ideas of reflection.

The essence of the soul is revealed mainly in its theoretical and practical activities. Locke calls the most general mode of theoretical activity representation, or perception. Well, the most general characteristic of the practical side of mental life is desire, or will. So, these are the cornerstones on which mental life stands: on perception and desire. Moreover, all other forms are derivatives, according to Locke. For example, memory, imagination, intellect - all these are derivatives of representation - all these are varieties of representation. Locke calls imagination, memory, sensation, doubt, anticipation, reason - he calls all this simple modes, modes of the simple idea of reflection, namely perception or representation.

And Locke also classifies complex ideas themselves. He divides them into three classes: ideas of substance, ideas of modes (the idea of a substance is, for example, a person - this is the idea of substance (which substance is not indicated here - just a substance, no matter what); mode (an example of a complex idea (not a simple mode, a complex) – the idea of beauty) and the idea of relationship (for example: cause is a correlative concept).

It limits reason only, in today's terms, to simple empirical judgments. This reflects the fact that Bacon's inductive method had a stronger influence on him than on Hobbes. Locke's philosophy can be characterized as a doctrine that is directly directed against the rationalism of Descartes (and not only against Descartes, but also in many ways against the systems of Spinoza and Leibniz). Locke denies...

... (the subject always realizes his cognitive interest in certain social conditions and bears their stamp). It is impossible to abstract from these influences when identifying the object of cognition. The formulation of the fourth problem of the theory of knowledge may sound like this: what are the content, forms, and patterns of the process of cognition? How is knowledge developing? Today, science distinguishes the sensual and...

In any philosophy textbook you can read that John Locke is an outstanding representative of the New Time era. This made a huge impression on the later masters of the minds of the Enlightenment. Voltaire and Rousseau read his letters. His political ideas influenced the American Declaration of Independence. Locke's sensationalism became the starting point from which Kant and Hume proceeded. And the ideas that human knowledge directly depends on sensory perception, which forms experience, gained extreme popularity during the thinker’s lifetime.

Brief description of the philosophy of the New Time

In the 17th-18th centuries, science and technology began to develop rapidly in Western Europe. This was the time of the emergence of new ones based on materialism, the mathematical method, as well as the priority of experience and experiment. But, as often happens, thinkers were divided into two opposing camps. These are rationalists and empiricists. The difference between them was that the former believed that we draw our knowledge from innate ideas, and the latter - that we process information that enters our brain from experience and sensations. Although the main “stumbling block” of the philosophy of the New Time was the theory of knowledge, nevertheless, thinkers, based on their principles, put forward political, ethical and pedagogical ideas. Locke's sensationalism, which we will consider here, fits perfectly into this picture. The philosopher belonged to the empiricist camp.

Biography

The future genius was born in 1632 in the English town of Wrington, Somerset County. When revolutionary events broke out in England, John Locke's father, a provincial lawyer, took an active part in them - he fought in Cromwell's army. Initially, the young man graduated from one of the best educational institutions of that time, Westminster School. And then he entered Oxford, which since the Middle Ages has been known for its university academic environment. Locke received a master's degree and worked as a Greek teacher. Together with his patron, Lord Ashley, he traveled a lot. At the same time, he became interested in social problems. But due to the radicalization of the political situation in England, Lord Ashley emigrated to France. The philosopher returned to his homeland only after the so-called “glorious revolution” of 1688, when William of Orange was proclaimed king. The thinker spent almost his entire life in solitude, almost as a hermit, but held various government positions. His friend was Lady Damerys Masham, at whose mansion he died of asthma in 1704.

Basic aspects of philosophy

Locke's views were formed quite early. One of the first thinkers to notice the contradictions in the philosophy of Descartes. He worked hard to identify and explain them. Locke created his own system partly to contrast it with Descartes. The rationalism of the famous Frenchman disgusted him. He was a supporter of all kinds of compromises, including in the field of philosophy. It was not for nothing that he returned to his homeland during the “glorious revolution”. After all, this was the year when a compromise was concluded between the main contending forces in England. Similar views were characteristic of the thinker in his approach to religion.

Criticism of Descartes

In our work “An Essay Concerning Human Reason” we see Locke’s concept already practically formed. There he spoke out against the theory of “innate ideas”, which was propagated and made very popular by Rene Descartes. The French thinker greatly influenced Locke's ideas. He agreed with his theories about certain truth. The latter should be an intuitive moment of our existence. But Locke did not agree with the theory that to be means to think. All ideas that are considered innate, according to the philosopher, in fact, are not. The principles that are given to us by nature include only two abilities. This is will and reason.

From a philosopher's point of view, the only source of any human ideas is experience. It, as the thinker believed, consists of individual perceptions. And they, in turn, are divided into external, cognizable by us in sensations, and internal, that is, reflections. The mind itself is something that uniquely reflects and processes information coming from the senses. For Locke, sensations were primary. They generate knowledge. In this process the mind plays a secondary role.

The Teaching of Qualities

It is in this theory that the materialism and sensationalism of J. Locke are most manifested. Experience, the philosopher argued, gives rise to images that we call qualities. The latter are primary and secondary. How to distinguish them? Primary qualities are constant. They are inseparable from things or objects. Such qualities can be called figure, density, extension, movement, number, and so on. What is taste, smell, color, sound? These are secondary qualities. They are impermanent and can be separated from the things that give rise to them. They also vary depending on the subject who perceives them. The combination of qualities creates ideas. These are a kind of images in the human brain. But they are simple ideas. How do theories arise? The fact is that, according to Locke, our brain still has some innate abilities (this is his compromise with Descartes). This is comparison, combination and distraction (or abstraction). With their help, simple ideas emerge into complex ones. This is how the process of cognition occurs.

Ideas and method

John Locke's theory of sensationalism not only explains the origin of theories from experience. She also categorizes different ideas according to criteria. The first of these is value. According to this criterion, ideas are divided into dark and clear. They are also grouped into three categories: real (or fantastic), adequate (or inconsistent with the models), and true and false. The last class can be attributed to judgments. The philosopher also spoke about what is the most suitable method to achieve real and adequate as well as true ideas. He called it metaphysical. This method consists of three steps:

- analysis;

- dismemberment;

- classifications.

We can say that Locke actually transferred the scientific approach to philosophy. His ideas in this regard turned out to be unusually successful. Locke's method prevailed until the 19th century, until he was criticized by Goethe in his poems that if someone wants to study something living, he first kills it, then dismembers it into pieces. But there is still no secret of life - there is only ashes in our hands...

About the language

Locke's sensationalism became the rationale for the emergence of human speech. The philosopher believed that language arose as a result of people having abstract thinking. Words are, in essence, signs. Most of them are general terms. They arise when a person tries to identify similar features of various objects or phenomena. For example, people have noticed that a black and a red cow are actually the same species of animal. Therefore, a general term has emerged to refer to it. Locke justified the existence of language and communication with the so-called theory of common sense. Interestingly, when literally translated from English, this phrase sounds a little different. It is pronounced "common sense". This led the philosopher to the idea that people tried to abstract from the individual in order to create an abstract term with the meaning of which everyone agreed.

Political ideas

Despite the philosopher’s secluded life, he was not alien to interest in the aspirations of the surrounding society. He is the author of Two Treatises on the State. Locke's ideas about politics boil down to the theory of "natural law". He can be called a classic representative of this concept, which was very fashionable in modern times. The thinker believed that all people have three basic rights - to life, freedom and property. To be able to protect these principles, man emerged from the state of nature and created the state. Therefore, the latter has corresponding functions, which are to protect these fundamental rights. The state must guarantee compliance with laws that protect the freedoms of citizens and punish violators. John Locke believed that in this regard, power should be divided into three parts. These are legislative, executive and federal functions (by the latter the philosopher understood the right to wage war and establish peace). They must be managed by separate bodies independent of each other. Locke also defended the right of the people to rebel against tyranny and is known for developing the principles of democratic revolution. However, he is one of the defenders of the slave trade, as well as the author of the political rationale for the policy of North American colonists who took land from the Indians.

Constitutional state

The principles of D. Locke's sensationalism are also expressed in his doctrine of the social contract. The state, from his point of view, is a mechanism that should be based on experience and common sense. Citizens waive their right to defend their own lives, freedom and property, leaving this to a special service. She must monitor order and implementation of laws. For this purpose, a government is elected by universal consent. The state must do everything to protect human freedom and well-being. Then he too will obey the laws. This is why a social contract is concluded. There is no reason to submit to the arbitrariness of a despot. If power is unlimited, then it is a greater evil than the absence of a state. Because in the latter case, a person can at least rely on himself. And under despotism he is generally defenseless. And if the state violates the agreement, the people can demand back their rights and withdraw from the agreement. The thinker's ideal was a constitutional monarchy.

About a human

Sensualism - the philosophy of J. Locke - also influenced his pedagogical principles. Since the thinker believed that all ideas come from experience, he concluded that people are born with absolutely equal abilities. They are like a blank slate. It was Locke who popularized the Latin phrase tabula rasa, that is, a board on which nothing has yet been written. This is how he imagined the brain of a newborn person, a child, in contrast to Descartes, who believed that we have certain knowledge from nature. Therefore, from Locke’s point of view, the teacher, by “putting into the head” the right ideas, can form the mind in a certain order. Education should be physical, mental, religious, moral and labor. The state must strive in every possible way to ensure that education is at a sufficient level. If it interferes with enlightenment, then, as Locke believed, it ceases to fulfill its functions and loses legitimacy. Such a state should be changed. These ideas were subsequently taken up by figures of the French Enlightenment.

Hobbes and Locke: what are the similarities and differences in the theories of philosophers?

It was not only Descartes who influenced the theory of sensationalism. the famous English philosopher who lived several decades earlier was also a very significant figure for Locke. Even the main work of his life - “An Essay on Human Reason” - he compiled according to the same algorithm by which Hobbes’ “Leviathan” was written. He develops the thoughts of his predecessor in the doctrine of language. He borrows his theory of relativistic ethics, agreeing with Hobbes that the concepts of good and evil for many people do not coincide, and only the desire to receive pleasure is the strongest internal drive of the psyche. However, Locke is a pragmatist. He does not set out to create a general political theory, as Hobbes does. Moreover, Locke does not consider the natural (stateless) state of man to be a war of all against all. After all, it was precisely with this provision that Hobbes justified the absolute power of the monarch. For Locke, free people can live spontaneously. And they form a state only by agreeing with each other.

Religious ideas

The philosophy of J. Locke - sensationalism - was also reflected in his views on theology. The thinker believed that an eternal and good creator created our world, limited in time and space. But everything that surrounds us has infinite variety, reflecting the properties of God. The entire universe is designed in such a way that every creature in it has its own purpose and a nature corresponding to it. As for the concept of Christianity, Locke's sensationalism manifested itself here in the fact that the philosopher believed that our natural reason discovered the will of God in the Gospel, and therefore it should become law. And the Creator’s requirements are very simple - you need to do good both for yourself and for your neighbors. Vice is to bring harm to one’s own existence and to others. Moreover, crimes against society are more important than crimes against individuals. Locke explains the Gospel demands for self-restraint by the fact that since constant pleasures await us in the other world, then for the sake of them we can refuse those that come. Whoever does not understand this is the enemy of his own happiness.

Locke's theory of knowledge

Priest Sergius Zavyalov

John Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding is one of the most important monuments of 17th-century philosophy. It is divided into four parts or books. “In the first he examines the question of the innate ideas of the mind and tries to prove that they do not exist. The second examines the question of where the mind receives its ideas. The third talks about the importance of language in knowledge and, finally, the fourth examines different types of knowledge along with faith and opinion” 1. For Locke, the theory of knowledge is not a secondary, but a main and even exclusive subject of study. Therefore, he is called: “the founder of the theory of knowledge as an independent discipline” 2. This is how he begins his work: “Since reason places man above other sentient beings and gives him all the superiority and dominion that he has over them, then he, without a doubt, is a subject worthy of study for its nobility alone. The understanding, like the eye, giving us the opportunity to see and perceive all other things, does not perceive itself: art and labor are needed to place it at some distance and make it its own object. But whatever may be the difficulties that lie in the way of this investigation, whatever may keep us so ignorant of ourselves, I am confident that every light we can throw on our own mental powers, every acquaintance with our own minds will be not only very pleasant, but also very useful, helping to direct our thinking to the study of other things” 3.

Locke developed a sensualist theory of knowledge. The starting point of this theory was the thesis about the experimental origin of all human knowledge.

Locke considered the main obstacle to knowledge to be the idealistic theory of innate knowledge, created by Plato and then developed by Descartes. According to this theory, our world is only a passive reflection of the supersensible world of ideas in which the human soul once lived. There she acquired a stock of knowledge.

Once in the earthly shell, the soul must remember all knowledge - this is the task of knowledge. From inductive observation of the more “natural” types of mind that people represent in a childish and savage state, Locke draws the conclusion that the presence of such concepts in the mind is not conscious. He says that "To exist in the mind" means the same thing as "to be conscious." Therefore, the theory of innate ideas falls into complete contradiction when it asserts that ideas are inherent in the mind, and at the same time that the mind does not know about them and comes to their awareness after long exercise and significant development” 4.

Denying the innateness of knowledge, Locke opposed the idealistic doctrine of the immaterial origin and essence of the soul and mind of man. “According to Locke, there is no innate knowledge, rules or principles; there is nothing in the mind that did not previously exist in the senses" 5 .

Having rejected innate ideas, Locke also opposed the recognition of innate “practical principles”, moral rules. Every moral rule, he argued, requires a reason, proof. Without a basis in the practical activity of people and without a stable conviction in the mind, a moral rule can neither appear nor be in any way durable. About what innate practical principles of virtue, conscience, reverence for God, etc. can there be any discussion, Locke said, if there is not even a minimal agreement among people on all these issues? Many people and entire nations do not know God, are in a state of atheism, and among religiously minded people and nations there is no identical idea of God. Some people do with complete calm what others avoid. The idea of God is a human affair. “In all the works of creation there are so clearly visible signs of extraordinary wisdom and power that any intelligent being who seriously thinks about them cannot fail to discover God.” 6 Locke then sums up his thoughts: “If the idea of God is not innate, no other can be considered innate. From what has been said above, I hope it is obvious that although the knowledge of God is the most natural discovery of human thinking, the idea of Him is nevertheless not innate.” 7

Developing a sensualist theory of knowledge, Locke distinguishes between two types of experience, two sources of knowledge: “external, which he calls “sensibility” (sensation), and internal, which he calls “reflection” (reflexion). The first arises as a result of the influence of the external world on the soul, the latter - as a result of the action of the soul on itself” 8. The source of external experience is the real world outside of us.

Internal experience - “reflection” - is the totality of the manifestation of all the diverse activities of the mind.

Rejecting innate ideas, he says: “Suppose the mind to be, so to speak, white paper (tabula rasa) without any signs or ideas. But how does he get them? Where does the vast supply of them come from, which the active and boundless human imagination has drawn with almost infinite variety? Where does he get all the material of reasoning and knowledge? To this I answer in one word: from experience. All our knowledge is based on experience; in the end, it comes from it” 9.

Locke argued that by experience we do not comprehend the existence of objects, but only their sensory qualities: “The presence of an idea of a thing in our mind, he says, does not prove the existence of that thing, any more than a portrait of a person proves his existence.” in the world, and how sleepy dreams do not prove true events” 10.

According to Locke, according to the methods of formation and formation, all ideas are divided into simple and complex. Simple ideas “are given to us from the outside, are imposed from the outside and cannot be changed either in number or in properties, just as particles of matter, for example, cannot be changed in number or properties” 11 . The mind is completely passive in the perception of these ideas, since both their number and properties depend on the nature of our abilities and the accidents of experience.

Simple ideas are all received directly from the things themselves, they are given to us:

a) one sense - “ideas” of color (vision), sound (hearing), etc.;

b) the activity of several senses together - “ideas” of extension, movement (touch and vision);

c) “reflection” - “ideas” of thinking and wanting;

d) feeling and “reflection” - “ideas” of strength, unity, continuity.

Complex ideas, according to Locke, are formed from simple ideas as a result of the mind's own activity. Complex ideas are a collection, a sum of simple ideas, each of which is a reflection of some individual quality of a thing.

John Locke identifies three main ways in which complex ideas can be formed:

1. "Under the name" MODES Locke does not mean ideas of something independent, but ideas of modifications of space, time, number and thinking. The very idea of space is derived from the sensations of sight and touch. Its modifications are given by modes: extension, distance, magnitude, figure, place. The idea of time comes from the reflection of a successive change of ideas, and Locke generally understands time as duration. Modifications of duration give modes: unity or unity, multitude, infinity. The idea of thinking stems from reflection. Modifications of thinking are given by the following modes: perceiving an idea, holding it, distinguishing, combining, comparing, naming and abstracting. These are the seven mental faculties allowed by Locke.

2. Another kind of complex ideas - ideas SUBSTANCES , by which Locke means ideas of something independent. These ideas come from the combination of several simple ideas gleaned from experience as properties of one and the same thing. There are physical substances, the main properties of which are the cohesion of particles and the power to impart movement, and spiritual substances, the main properties of which are thought and will...

3. The third kind of complex ideas are ideas RELATIONS , arising from the observation of objects related to each other. Relationship ideas are countless; the most important things between them: identities, differences, causality” 12.

The mind creates complex ideas. The objective basis for the creation of the latter is the consciousness that outside of man there is something that connects into a single whole things that are separately perceived by sensory perception. In the limited accessibility to human knowledge of this objectively existing connection of things, Locke saw the limited possibilities of the mind's penetration into the deep secrets of nature. However, he believes that the inability of the mind to obtain clear and distinct knowledge does not mean that a person is doomed to complete ignorance. A person’s task is to know what is important for his behavior, and such knowledge is quite accessible to him. According to Locke: “knowledge is only the perception of connection and compliance or the inconsistency and incompatibility of any of our ideas... Where there is this perception, there is also knowledge: where it is not, there we can, however, imagine, guess or believe, but we never have knowledge” 13.

There are two types of knowledge: reliable and unreliable. Reliable knowledge is that which corresponds to reality; unreliable must be those which, at their origin, were modified through reflection, as a result of which a subjective element entered into them, which violated their original correspondence to its object. It turns out that reliable knowledge “can only be those that are perceived by us passively in external or internal observation, which are all simple ideas.

However, everything that is formed by the activity of our mind must be unreliable” 14.

Locke identified two degrees of knowledge. 1) Intuitive, acquired directly or visually, which the mind receives from assessing the consistency or inconsistency of ideas with each other. 2) Demonstrative, acquired through evidence, for example, through comparison and relation of concepts. Demonstrative cognition necessarily presupposes the existence of intuitive knowledge, since inference requires that those judgments that serve as premises be known.

However, “the difference between intuitive and demonstrative knowledge is not that the former is more reliable than the latter, but that the former (for example, three is one and two, white is not black) immediately evokes agreement, whereas the latter often only through hard research does one force this consent” 15.

Locke also singles out sensory knowledge of the existence of individual things; it is aimed at individual facts or a certain sum of individual facts, “extending beyond simple probability, but not reaching the fully specified degrees of certainty, it is considered knowledge” 16.

The most reliable type of knowledge, according to Locke, is intuition. Intuitive knowledge is the clear and distinct perception of the agreement or inconsistency of two ideas through direct comparison. “As for our own existence, it is so obvious that it does not need any proof. Even if I doubt everything, then this very doubt convinces me of my existence and does not allow me to doubt it. This belief is completely immediate (intuition) 17.” Here Locke is completely in line with the point of view of Descartes' Cogito ergo sum.

Locke's demonstrative knowledge is in second place after intuition, in terms of reliability. In this type of cognition, the perception of the correspondence or inconsistency of two ideas is not accomplished directly, but indirectly, through a system of premises and conclusions. The third type of knowledge - sensual or sensitive - is limited to the perception of individual objects of the external world. In terms of its reliability, it stands at the lowest level of knowledge and does not achieve clarity and distinctness.

In the field of knowledge, Locke distinguishes two types of general judgments: judgments formed by simple decomposition of a concept, which do not contain anything new in comparison with this concept; and judgments, which, although formed on the basis of some concept and necessarily follow from it, carry within themselves something that is not yet contained in the concept itself.

Truth or knowledge as the agreement of ideas among themselves is manifested in four different ways of relating ideas: 1) in their identity or difference, 2) in the relationship between them, 3) in coexistence (or necessary connection) and 4) in the reality of their existence.

According to Locke, knowledge of the existence of something is possible only in relation to two ideas - the idea of “I” and the idea of “God”. The existence of the idea of “I” is obtained intuitively, and the existence of the idea of “God” is demonstrative.

“The proof of the existence of God comes from the intuitive knowledge of the existence of the “I” and consists in the following conclusion: everything that has a beginning is caused by another being, and therefore there must be a beginningless creating being and, moreover, it must be a being with the highest intelligence, since I am a created thinking being" 18 . Our confidence in the existence of the external world is based on the same demonstrative knowledge: “God has given me sufficient confidence in the existence of things outside of me: through different handling of them I can cause in myself both pleasure and pain, which is the only thing important to me in my present situation.” " 19 .

So, according to Locke, the existence of external objects, the existence of God and our own existence are not subject to any doubt. Although neither the soul, nor God, nor the world in itself are given to us in sensory perception. Our knowledge of these subjects, despite its imperfection, “is quite sufficient for life here” 20.

“It has rarely happened that a philosopher with one work has achieved such fame and such a name for himself, and achieved such influence in the history of thought, as Locke did with his Essay.” All modern historians of philosophy consider Locke to be a first-class thinker, along with Descartes, Bacon, Spinoza, Leibniz, and recognize him as the true predecessor of Kant, the founder of the newest critical theory of knowledge, as well as psychology” 21.

Notes

1 Grot N.Ya. Key points in the development of the new philosophy. M. 1894. – P. 115.

2 KülpeO. Introduction to philosophy. SPb. 1901. – P. 37.

3 Locke D. Works in three volumes. T. 1. – M. 1985. – P. 91.

4 Markov N., priest. Review of philosophical teachings. M. 1880. – P. 59.

5 FullierA. History of philosophy. SPb. 1901. – P. 243.

6 Locke D. Works in three volumes. T. 1. – M. 1985. – P. 139.

7 Locke D. Works in three volumes. T. 1. – M. 1985. – P. 145.

8 RemkeI. Essay on the history of philosophy. SPb. 1898. – P. 172.

9 Locke D. Works in three volumes. T. 1. – M. 1985. – P. 154.

10 Gabriel, archim. History of philosophy. Part 4. – Kazan. 1839. – P. 29.

11 Ostroumov M. Review of philosophical teachings. Tambov. 1877. – P. 77.

12 Ostroumov M. Review of philosophical teachings. Tambov. 1877. – pp. 78-79.

13 Locke D. Works in three volumes. T. 2. – M. 1985. – P. 3.

14 Ostroumov M. Review of philosophical teachings. Tambov. 1877. – P. 81.

15 Remke I. Essay on the history of philosophy. SPb. 1898. – P. 178.

16 Locke D. Works in three volumes. T. 2. – M. 1985. – P. 14.

17 Markov N., priest. Review of philosophical teachings. M. 1880. – P. 61.

18 Remke I. Essay on the history of philosophy. SPb. 1898. – P. 180.

19 Locke D. Works in three volumes. T. 2. – M. 1985. – P. 14.

20 Ostroumov M. Review of philosophical teachings. Tambov. 1877. – P. 86.

21 Grot N.Ya. Key points in the development of the new philosophy. M. 1894. – P.106.

Sources and literature used

1. Gabriel, archim. History of philosophy. Part 4. – Kazan: Univer. Type. 1839. – 192 p.

2. Grot N.Ya. Key points in the development of the new philosophy. M.: Type. "Dawn". 1894. – 256 p.

3. History of philosophy: West-Russia-East. Book two: Philosophy of the 15th – 19th centuries / Ed. Motroshilova N.V. M. 1996. – 557 p.

4. Kulpe O. Introduction to philosophy. St. Petersburg: Knigoizd. Popova. 1901. – 343 p.

5. Lega V.P. Lectures on the history of philosophy. Part 2. M. 1999. – 164 p.

6. Locke D. Works in three volumes. T. 1. – M.: Thought. 1985. – 621 p.

7. Locke D. Works in three volumes. T. 2. – M.: Thought. 1985. – 560 p.

8. Markov N., priest. Review of philosophical teachings. M.: Type. Lavrova. 1880. – 228 p.

9. Ostroumov M. Review of philosophical teachings. Tambov: Provincial Zemskaya type. 1877. – 259 p.

10. Remke I. Essay on the history of philosophy. SPb.: Type. Goldberg. 1898. – 344 p.

11. Fullier A. History of philosophy. St. Petersburg: Electroprinting. 1901. – 360 p.

Locke was the first to formulate the foundations of empiricism and develop a sensualistic theory of knowledge.

Locke's masterpiece was the famous "Essay Concerning Human Understanding" - his main philosophical work, the result of almost twenty years of work, published in 1690.

Locke's area of interest included three topics: a) epistemology; b) ethical and political issues; c) religion. To these we can add a fourth subject – pedagogy.

Bacon wrote that necessity is “the introduction of a better and more perfect use of reason.” Locke made this problem a program and implemented it. However, it was important for him to explore the mind itself, its abilities, functions and limits. The task becomes to determine the limits within which the human mind can and must operate, as well as the limits beyond which it must not be exceeded.

“Knowing our cognitive abilities protects us from skepticism and mental inactivity. When we know our strengths, we will know better what we can do with the hope of success... Our task here is to know not everything, but what is important for our behavior.”

“...The first step towards the solution of the various questions which the human soul almost certainly must have to face, is to examine our own minds, to study our own powers and what they apply to.”

Locke's concept states that ideas come from experience and therefore experience is the limit of knowledge.

In both Descartes and Locke, the idea loses its ancient meaning of form and substantial essence. However, Descartes took the position of innate ideas. Locke, on the contrary, denies any form of innateness and seeks to prove that ideas come only from experience.

Locke's concept has the following provisions: 1) there are no innate ideas or principles; 2) no human mind is capable of forming or inventing ideas, nor can it destroy existing ideas; 3) the source and at the same time the limit of reason is experience.

The criticism of innate ideas is seen by Locke as a defining moment. “...It is absurd to claim that small children or the mentally retarded possess these principles “innately,” but are not aware of them...”

“To say that a concept is imprinted in the consciousness, in the soul, and at the same time declare that the soul does not know about it and has never guessed about it before, means turning it into nothing.”

The assertion of innate moral principles is refuted by the fact that some peoples behave in direct opposition to such principles, i.e. They commit acts that are villainous from our point of view and do not feel any remorse.

Locke rules out that the mind could create ideas. Our mind can combine the ideas it receives in various ways, but in no way can it itself produce even simple ideas, but if it has them, it cannot destroy them.

This means that the mind receives the material of knowledge exclusively from experience. The soul thinks only after receiving such material.

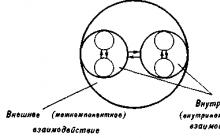

There are two types of experience. There are external material objects and internal activity of the soul and thoughts. Hence there are two different types of simple ideas. From the first arise sensations received both from one sense organ (for example, the ideas of color, sound, taste) and from several senses (for example, the ideas of extension, figure, motion and state of rest). From the second arise simple reflective ideas (for example, the idea of thinking and wanting, or simple ideas such as the idea of pleasure, pain, power, etc.).

Ideas are in the mind of man, but there is something outside that has the power to produce ideas in the mind. This ability of things to produce ideas in us is what Locke calls “quality.”

Locke introduces this distinction to understand the theory of primary and secondary qualities. The former represent “the primary and real qualities of bodies that are always found in them (i.e. density, extension, shape, quantity, motion or state of rest...).” Secondary “are combinations of primary qualities,” such as taste, color, smell, etc. Primary qualities are objective in the sense that the corresponding ideas evoked in us are exact copies of objects that exist outside of us. In contrast, secondary qualities - color, smell, taste - are subjective in the sense that they do not reflect the objective properties of the things themselves, although they are caused by them.

In receiving simple ideas our soul is passive; but having already received such ideas, she has the opportunity to perform various actions with them, in particular, she can combine ideas with each other and thus form complex ideas.

Some simple ideas are always connected to each other. Suppose there is a certain substrate from which ideas are formed - “substance”. Locke does not deny the existence of substances, he denies the fact that we have a clear idea of them. From our experience we learn about qualities, but substance is the bearer of quality, and we cannot comprehend it. We do not comprehend the object in a single act - we add up the qualities that we perceive. Substance is not a specific object, but a certain substrate, a certain support, the basis for the unity of all objects. We do not have the instrument to know this subject accurately. It turns out that there is an idea of substance, but there can be no clarity and distinctness in relation to it.

For Locke, ideas are the material of knowledge, and he notes that ideas themselves are not yet knowledge, because they are outside the criteria of truth and falsity, they arise due to the influence of objects. Cognition is an understanding of the connection between the consistency or inconsistency of ideas. The first way of cognition is intuition (in comprehending the consistency of an idea) - a phenomenon of immediate evidence. The second way is to prove understanding through deduction, inference, etc. That is, reflection. Reflection exists so that we can make connections where coherence of ideas is not immediately obvious.

LOCKE IS ONE OF THE FIRST THINKERS WHO NOTES THE CLOSE RELATIONSHIP OF THINKING AND LANGUAGE. “Words do not mean the things themselves, but the ideas of things.” The doctrine of language is based on the doctrine of primary and secondary qualities. Only primary qualities are exact copies of things. Often the idea that a word represents is not entirely clear—the language needs clarification.

By the middle of the 17th century, the reform movement intensified in England and the Puritan church established itself. In contrast to the powerful and fabulously rich Catholic Church, the Reform movement preached the rejection of wealth and luxury, economy and restraint, hard work and modesty. The Puritans simply dressed, refused all kinds of decorations and accepted the simplest food, denied idleness and empty pastime and, on the contrary, welcomed constant work in every possible way.

In 1632, the future philosopher and educator John Locke was born into a Puritan family. He received an excellent education at Westminster School and continued his academic career as a teacher of Greek and rhetoric and philosophy at Christ Church College.

The young teacher was interested in the natural sciences, and especially chemistry, biology and medicine. In college, he continues to study the sciences that interest him, while he is also concerned about political and legal issues, ethics and educational issues.

At the same time, he became close to the king’s relative, Lord Ashley Cooper, who led the opposition to the ruling elite. He openly criticizes royal power and the state of affairs in England, and boldly speaks out about the possibility of overthrowing the existing system and forming a bourgeois republic.

John Locke leaves teaching and settles on Lord Cooper's estate as his personal physician and close friend.

Lord Cooper, together with the opposition-minded nobles, is trying to make his dreams come true, but the palace coup failed, and Cooper, together with Locke, has to hastily flee to Holland.

It was here, in Holland, that John Locke wrote his best works, which later brought him worldwide fame.

Basic philosophical ideas (briefly)

John Locke's political worldview had a huge influence on the formation of Western political philosophy. The Declaration of the Rights of Man, created by Jefferson and Washington, builds on the teachings of the philosopher, especially in such sections as the creation of three branches of government, the separation of church and state, freedom of religion and all matters relating to human rights.

Locke believed that all the knowledge acquired by humanity over the entire period of existence can be divided into three parts: natural philosophy (exact and natural sciences), practical art (this includes all political and social sciences, philosophy and rhetoric, as well as logic), teaching about signs (all linguistic sciences, as well as all concepts and ideas).

Western philosophy before Locke was based on the philosophy of the ancient scientist Plato and his ideas of ideal subjectivism. Plato believed that people received some ideas and great discoveries even before birth, that is, the immortal soul received information from space, and knowledge appeared from almost nowhere.

Locke, in many of his writings, refuted the teachings of Plato and other “idealists,” arguing that there was no evidence for the existence of an eternal soul. But at the same time, he believed that such concepts as morality and ethics are inherited and that there are people who are “morally blind,” that is, who do not understand any moral principles and are therefore alien to human society. Although he also could not find evidence for this theory.

As for the exact mathematical sciences, most people have no idea about them, since learning these sciences requires long and methodical preparation. If this knowledge could be obtained, as the agnostics argued, from nature, then there would be no need to strain, trying to understand the complex postulates of mathematics.

Features of consciousness according to Locke

Consciousness is the ability of only the human brain to display, remember and explain existing reality. According to Locke, consciousness resembles a blank white sheet of paper on which, starting from the first birthday, you can reflect your impressions of the world around you.

Consciousness relies on sensory images, that is, obtained with the help of the senses, and then we generalize, analyze and systematize them.

John Locke believed that every thing came into being as a result of a cause, which in turn was the product of an idea of human thought. All ideas are generated by the qualities of already existing things.

For example, a small snowball is cold, round and white, so it gives rise to these impressions in us, which can also be called qualities . But these qualities are reflected in our consciousness, which is why they are called ideas. .

Primary and secondary qualities

Locke considered the primary and secondary qualities of any thing. The primary ones include the qualities necessary to describe and consider the internal qualities of each thing. These are the ability to move, figure, density and number. The scientist believed that these qualities are inherent in every object, and our perception forms the concept of the external and internal state of objects.

Secondary qualities include the ability of things to generate certain sensations in us, and since things are able to interact with people’s bodies, they are able to awaken sensory images in people through vision, hearing and sensations.

Locke's theories are quite unclear regarding religion, since the concepts of "God" and "soul" were immutable and sacrosanct in the 17th century. One can understand the scientist’s position on this issue, since, on the one hand, Christian morality dominated him, and on the other, together with Hobbes, he defended the ideas of materialism.

Locke believed that “the highest pleasure of man is happiness,” and only it can make a person purposefully act to achieve what he wants. He believed that since every person is attracted to things, it is this desire to possess things that makes us suffer and experience the pain of unsatisfied desire.

At the same time, we experience double feelings: since possession causes pleasure, and the impossibility of possession causes mental pain. Locke included such feelings as anger, shame, envy, and hatred as concepts of pain.

Locke's ideas regarding the state of state power at various stages of development of the human collective are interesting. Unlike Hobbes, who believed that in the pre-state state there was only the “law of the jungle” or the “law of force,” Locke wrote that the human collective was always subject to rules more complex than the law of force, which determined the essence of human existence.

Since people are, first of all, rational beings, they are able to use their reason to control and organize the existence of any group.

In the state of nature, every person enjoys freedom as a natural right given by nature itself. Moreover, all people are equal both in relation to their society and in relation to rights.

Concept of property

According to Locke, only labor is the basis for the emergence of property. For example, if a person planted a garden and patiently cultivated it, then the right to the result obtained belongs to him on the basis of the labor invested, even if the land does not belong to this worker.

The scientist's ideas about property were truly revolutionary for that time. He believed that a person should not have more property than he can use. The very concept of “property” is sacred and protected by the state, so inequality in property status can be tolerated.

The people as the bearer of supreme power

As a follower of Hobbes, Locke supported the “social contract theory,” that is, he believed that people enter into a contract with the state, giving up part of their natural rights in exchange for the state protecting them from internal and external enemies.

At the same time, the supreme power is necessarily affirmed by all members of society, and if the supreme overlord does not cope with his responsibilities and does not justify the trust of the people, then the people can re-elect him.

Personnel accounting and payroll calculation in "1C:ERP" Document "Reflection of salaries in financial accounting"

Which account is used to record banking transactions?

Free programs for small and medium-sized businesses Program for automation of production accounting

Using information technology to improve the efficiency of human resources services of organizations Personnel work in municipalities

The image of the mother in fiction The image of the mother in Russian literature